|

September 1964 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

On April 20, 1964, AT&T

introduced the Picturephone at the New York World's Fair, enabling coast-to-coast

video communication. The device, which featured a 4-3/8" x 5-3/4" screen and push-button

controls allowing users to display themselves, others, or nothing at all, went into

commercial service on June 24 with public booths in New York, Washington, and Chicago.

The article notes that the concept of video telephony was first imagined in Hugo

Gernsback's 1911 science fiction novel "Ralph 124C 41+," where it was called the

"Telephot." While initially expensive ($16-$27 for three minutes depending on cities

connected), the Mr. Gernsback, in this 1964 editorial, predicts the technology

would eventually become more affordable and evolve to include features like language

translation, 3D capabilities, and color display, potentially revolutionizing activities

like shopping by allowing consumers to see products remotely in full color.

The Picturephone in Your Future... Immense Are the Coming

Applications of This Great Device ...

Front cover of the April 1911 issue of Modern Electrics,

illustrating the use of the earliest known Telephot, now called the Picturephone.

By Hugo Gernsback

On April 20, 1964, the American Telephone & Telegraph Co. unveiled its newest

device, the Picturephone, at the New York World's Fair. (The Picturephone is shown

on page 6 of the July 1964 Radio-Electronics.) Viewers could see people across the

country, as far away as Los Angeles, Calif., in a coast-to-coast press conference.

Ever since, the long-awaited "See-as-you-talk" phone has been drawing huge crowds

at the AT&T pavilion at the Fair. There, soundproof booths equipped with Picturephones

allow visitors to talk with each other or with a nearby telephone operator. Visitors

sit about 3 feet from the little instrument's screen, housed in a small desktop

table set. Normal room illumination is sufficient for the little vidicon tube next

to the set's screen to give a good picture. On June 24, the Picturephone went into

commercial use in a circuit linking public booths in New York, Washington and Chicago.

Picture size is 4 3/8 x 5 3/4 inches. The control set uses no dial; it has push

buttons which allow you to see yourself, another person or nothing at all at your

choice.

The idea of the long-distance Picturephone is hoary with age. It probably was

first used anywhere in word and picture in my novel, Ralph 124C 41+ (A Romance of

the Year 2660), originally published in installments beginning with the April 1911

issue of Modem Electrics, forerunner of Radio-Electronics.

For the record, 53 years ago the instrument was known as the Telephot. As the

story opens, Ralph 124C 41+, one of the world's most renowned scientists and one

of the ten celebrated Plus men of the Planet, is talking from New York long distance

to a friend, over the telephot.

Suddenly there is an interruption, just as we have today - and the screen of

the telephot goes blank. Then:

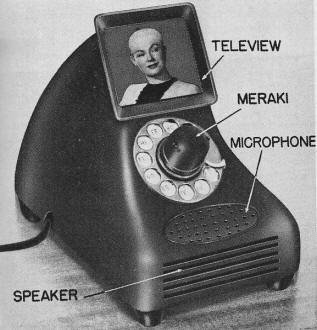

This 1925 illustration of the Telephot, now known as the

Picturephone, appeared in the first book reprint of the novel RALPH 124C 41+. Note

microphone on top of loudspeaker, openings at left. The Telephot also foresaw the

Language Rectifier, so far not realized.

"At this moment the voice ceased and Ralph's faceplate be-came clear. Somewhere

in the Teleservice company's central office the connection had been broken. After

several vain efforts to restore it Ralph was about to give up in disgust and leave

the Telephot when the instrument began to glow again. But instead of the face of

his friend there appeared that of a vivacious beautiful girl. She was in evening

dress and behind her on a table stood a lighted lamp.

"Startled at the face of an utter stranger, an unconscious 'Oh!' escaped her

lips, to which Ralph quickly replies:

"'I beg your pardon, but 'Central' seems to have made another mistake. I shall

certainly have to make a complaint about the service.'

"Her reply indicated that the mistake of 'Central' was a little out of the ordinary,

for he had been swung onto the Intercontinental Service as he at once understood

when she said, 'Pardon, Monsieur, je ne comprends pas!'

"He immediately turned the small shining disc of the Language Rectifier on his

instrument till the pointer rested on 'French.' "

This starts the great international and interplanetarian romance, with the heroine,

Alice, in distant Switzerland. Ralph subsequently saves her, via electronics, from

an immediately threatening avalanche.

While the Picturephone is now an assured fixture, what are its implications for

the future?

At present, while it is new, it still is a luxury. AT&T made public its rates:

$16 for the first three minutes between New York and Washington, $21 between Chicago

and Washington, and $27 between Chicago and New York.

These rates, in the foreseeable future, will naturally come down and will, in

all probability, with electronic advances, approach the prevailing long-distance

phone charges.

What about other foreseeable necessary technical advances of the future? Ralph

in the story spoke of a Language Rectifier. A great deal of work on this internationally

necessary invention has already been accomplished by scores of laboratories all

over the world. We would be surprised if the problem were not solved by 1975, at

the present rate of progress of the electronic computer.

Probably the next requirement is 3D or three-dimensional TV. We have mentioned

this at length and frequently on this page. Anyone who has ever watched a baseball

game or other sports has been struck by the inadequacy of the two-dimensional, flat

TV picture of our present-day sets. Technicians and inventors know that 3D will

be achieved without question in the future. Our own guess: The solution most likely

may lie in a multiple transparent screen that will show the picture in depth, perhaps

with a plurality of split cathode rays.

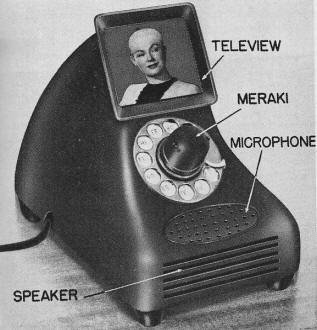

From TAME Magazine - a parody of TIME - published Christmas,

1944. A more up-to-date version of the Picture phone, then called Teleview, as illustrated

here. Note the microphone and speaker. Meraki permits dialing from a distance of

10-25 feet. Another Meraki [Menos (mind)-radio-kinetics] is worn on the head of

the person using the instrument. His brain waves operate the Meraki transmitter,

signals from which dial the telephone. The girl's bald head is a proposed hygienic

development, supposedly to come by 2044.

Finally, the perfected Picturephone, to be universally acceptable, must of necessity

be in full color.

We can see a vast and unbelievable expansion of the future Picturephone as a

shopping instrumentality alone. Here is why:

Shopping today is a major chore - and it will be worse in the future - because

of our totally inadequate streets, over-crowded stores, impossible traffic, time

loss and general frustration in shopping from store to store.

In the future you will be shopping by Picturephone while you stay either home

or at your office. If you are a man, let us say, and you wish to buy a number of

ties, you can do it in minutes, thanks to the color Picturephone. You will see every-thing

you buy in full natural colors. If your wife wants to buy a dress or a pair of slacks

- she sees them in the real colors. Or she may want to buy a rug, a pair of shoes

or what not. Now she sees what she buys, without any guesswork. Most of the frustration

is now eliminated.

All this, however, is only a single application of the Picturephone.

There are literally thousands of other uses: "Whenever it is too difficult; too

dangerous; too expensive; too inconvenient; too inaccessible; too far; too hot;

too cold; too high; too low; too dark; too small to observe directly-use television,"

says an excellent book, Television in Science and Industry, written in 1958 by V.

K. Zworykin, famed inventor of the iconoscope and the kinescope. And, we might add,

don't overlook the hundreds of new uses of the finally improved future Picturephone.*

Finally and parenthetically, may we delicately but firmly point out one fact

to the wildly perturbed lady columnists who, lately en masse have denounced the

perfectly innocent Picturephone as a nasty electronic ogre and a horrible example

of a new infraction of woman's privacy.

The simple technological fact is this: No one, least of all the Picturephone,

could possibly intrude on your privacy, unless you want it to. There is a button

or a switch you must press first to become visible to a caller.

No press, no see! See! -H.G.

* See also the long list of industrial and other uses in Atypical Television,

Radio-Electronics, October, 1958.

|