|

December 1968 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

As with so many aspects

of electronics, physics, economics, medicine (well, maybe not medicine), the basics

do not change a whole lot since first being discovered. If you are a newcomer to

the world of electronics and are trying to come up to speed on transistor construction

and operation, even this article that appeared in a 1968 issue or Radio-Electronics

magazine will be useful to you. Figure 1 reminds me of a situation I witnessed

while working as a technician at Westinghouse Oceanic Division, in Annapolis, Maryland.

If you've heard this before, please indulge me. One of the managers there, who was

not a degreed engineer (although he held the title), one day while in the lab actually

soldered a pair of 1N4148 diodes together back-to-back per Figure 1 and tried

biasing it to function like a transistor. A "real" engineer, whom I greatly admired,

stood watching with his mouth agape as he watched. Before he could politely explain

why the diode pair is not the same as the intimate PN junctions of an actual transistor,

another "real" engineer who had no compunction about dressing down someone for a

stupid action lost no time setting the poor guy straight. The real tragedy is that

the engineer-in-title-only (who was a very nice guy, BTW) didn't know enough about

basic semiconductor physics to even understand what was being explained.

ABC's of Transistors - Here's How They Work

Fig. 1 -Transistor diode junction equivalent schematic.

Fig. 2 - NPN and PNP transistor schematic symbols.

Fig. 3 - Base-emitter and collector-emitter biasing.

Transistors have puzzled technicians for nearly a decade and there appears to

be no sign of easing the strain. Each year more transistorized equipment is introduced

in both television and hi-fi equipment. To keep up to date we must learn efficient

transistor servicing procedures.

Many articles have been devoted to transistor troubleshooting and all of them

have leaned heavily on theory. But many successful technicians working on vacuum-tube

circuits do not have a solid foundation in vacuum-tube theory, so perhaps the solid-state

troubleshooter does not necessarily need theory. Let's look at transistors from

a troubleshooter's standpoint and minimize the theory.

For those of you with experience with tubes here is a comparison of transistors

and tubes: A transistor is somewhat like a tube: Corresponding elements are:

- Tube-Transistor

- Cathode-Emitter

- Grid-Base

- Plate-Collector

There are two important differences:

- The tube is a voltage amplifier.

- The transistor is a current amplifier.

The grid of a tube usually has an opposite potential to the cathode and plate

of a tube, but the transistor base potential is between the emitter and collector

potentials.

Just Two Diodes

Transistors are further complicated as there are two types which operate with

opposite bias and supply voltage polarities.

Yet it is easy to determine proper polarities for bias and supply voltages and

what voltages we can expect in standard circuit configurations for each type.

The two basic types are, of course, pnp and npn. Physical and electrical characteristics

of pnp and npn transistors are shown in Fig. 1. Both transistors are shown

electrically as two diodes wired back to back. In the pnp type the cathodes are

tied together; in the npn type the anodes are connected. The junction represents

the base connection with the emitter or collector at either end.

Two common symbols for both pnp and npn transistors are in Fig. 2. Note

that the arrows in both the diodes and the transistor symbol point in the same direction.

Remember this and you cannot go wrong.

Normal Circuit Parameters

Fig. 4 - Base current direction for PNP and NPN transistor.

In conventional circuits a small forward bias, normally 0.2 to 0.7 volt, is applied

to the emitter junction. An easy way to remember which polarity is required to forward-bias

a junction is to note that, when a negative voltage is applied to an n-element and

a positive voltage to a p-element of a pn junction, it is forward-biased. This is

shown in Fig. 3. The letters tell you the crystal type in each element. That

is, pnp stands for p-type (crystal) emitter, n-type base and p-type collector. npn

stands for n-type emitter, p-type base and n-type collector.

In other words, for a forward-biased emitter junction, a pnp transistor requires

a negative voltage on the base with respect to the emitter. To forward-bias an npn

transistor emitter junction a positive voltage on the base, with respect to the

emitter, is required.

The collector circuit, on the other hand, requires a back-bias or reverse bias.

So in a pnp transistor, a negative voltage is required on the collector with respect

to the base and the opposite for an npn transistor. Circuits with these typical

configurations are shown in Fig. 4. Note that the bias batteries are connected

so they aid one another.

The Need for Biasing

Biasing is used in transistor circuits for the same reason that it is used in

tube circuits-to set up a static operating point. Without proper bias, what was

intended to be a class-A amplifier might operate class-B.

The simplest bias is accomplished with a single-resistor network. A common-emitter

amplifier with a single bias resistor is shown in Fig. 5. Since the emitter-junction

resistance is quite low, the base bias current can be calculated by dividing the

bias voltage by base bias resistor. The base resistance is ignored because it is

very small compared to the base bias resistor.

In Fig. 6-a, the negative terminal of the power supply is grounded. In Fig. 6-b,

the positive terminal of the power supply is grounded. Each circuit's operation

is identical. The resistors form a voltage divider network and selection of various

values can result in any voltage between the supply and zero volts to appear at

the base of the transistor. If there is a 0.7-volt difference between base and emitter,

the transistor is turned on and emitter/collector current flows. If this voltage

difference is reduced, less collector/emitter current flows. Conversely if this

voltage difference is increased, collector/emitter current increases.

Fig. 5 - PNP transistor DC biasing.

In Fig. 6-a, if a 10-volt supply is used, R2 will be approximately 9 times

as large as R1 and +0.7-volt appears at the base. In Fig. 6-b, the values of

R1 and R2 stay the same, but their relative positions are reversed to effect a +9.3-volt

potential on the base. Either way, the base is +0.7-volt with respect to the emitter.

The voltages shown are typical for a silicon transistor. Note that the base voltage

is closest to the emitter voltage and between collector-emitter voltage.

An important consideration is the polarity and magnitude of voltage that must

be applied to the base/emitter junction to turn the transistor "on" and cause electron

flow between emitter and collector. While a tube requires bias voltage to reduce

electron flow, the transistor requires bias current to cause electrons to flow.

A tube with zero bias between grid and cathode generally has heavy current flow

while a transistor with zero bias between base and emitter is shut off and no current

flows between collector and emitter.

To forward-bias or "turn on" a transistor, a small voltage is applied between

the base and emitter elements. When measured from the emitter, the polarity of this

bias voltage is the same as the collector voltage but its value is much lower.

Fig. 6 - Emitter self-biasing.

Fig. 7 - Emitter stabilizing resistor.

Fig. 8 - Class A (linear) transistor biasing.

Fig. 9 - Input - output voltage waveforms.

Remember, as the voltage on the base element changes in the direction of the

collector potential, the emitter/collector current increases. If the voltage on

the base element moves in the direction of the emitter potential, the emitter/collector

current decreases. This is true regardless of whether the transistor is silicon

or germanium and npn or pnp.

In Fig. 7, resistor R3 is in series with the emitter. It stabilizes collector

current and is referred to as a stabilizing resistor. As collector current flows

through emitter resistor R3, a voltage is developed which opposes the forward-bias

voltage. The effect of R3 is to oppose any change in current flow since the voltage

across it is in series with the forward-bias voltage. For example, if collector

current increases, the voltage drop across R3 increases and reduces the effective

forward bias which, in turn, reduces collector current.

Conversely, if collector current decreases, less voltage is developed across

R3 and the effective forward bias increases. This, in turn, increases collector

current. Adding an emitter resistor stabilizes a transistor with respect to collector-current

variations which occur for a variety of reasons. The most common cause is an increase

in collector current as a result of temperature increase.

When troubleshooting, the voltage drop across the emitter resistor is an important

test point for checking circuit operation. A higher than normal emitter voltage

generally indicates excessive collector current. This can be caused by a shorted

transistor or a bias defect. A lower than normal emitter resistor voltage would

indicate an open transistor or bias defect.

Class-A Amplifier

A transistor stage set up for class-A or linear operation is shown in Fig. 8.

In this stage. bias resistor R3 is shown as an adjustable unit, so some desired

collector current will flow. This control can be used to show how the transistor

amplifies the input signal.

The base voltage-collector current curve in Fig. 8 shows the collector current

for several bias voltages. The horizontal line shows bias voltages developed across

bias resistor R3. The vertical line shows values of collector current for each value

of bias and we will neglect the effect of emitter resistor R4.

Note the mark on the bottom line indicating 2.4 V. This actually means 0.1 V

between the base and emitter since the emitter is at +2.3 V. This mark corresponds

with a line on the vertical column marked "minimum" as indicated by the dotted lines.

This means that, with 0.1 V forward bias, only a small amount of collector current

will flow.

If R3 is adjusted to make the base voltage become 3 V (0.7 V between base and

emitter), the collector current increases. Referring again to the curve, we see

that the collector current has increased to the mark on the vertical column marked

"normal".

If R3 is adjusted to make the base voltage become +3.6 V (1.3 between base and

emitter). there will be an increase in collector current. The collector current

has increased to the "maximum" level.

From this we can see that by varying the base voltage, we can produce any desired

value of collector current. In practice, the emitter voltage would not remain constant

with different values of collector current. This action is similar to cathode-voltage

variation in a tube.

An AC signal fed to the base element can also cause collector-current changes.

Referring again to Fig. 8, we adjust R3 to make the base voltage become +3

V. This causes a collector current that corresponds to "normal" on the curve. The

collector current through R2 causes a voltage drop so about half the supply voltage

appears at the collector. These are the necessary conditions for a linear stage

(amplification without distortion).

An AC generator supplies a signal between the base of the transistor and chassis

ground in Fig. 9. This signal at any instant will add or subtract from the

de bias supplied by bias resistors R1 and R2. Capacitor C2 provides an AC bypass

across R3 at the signal frequency.

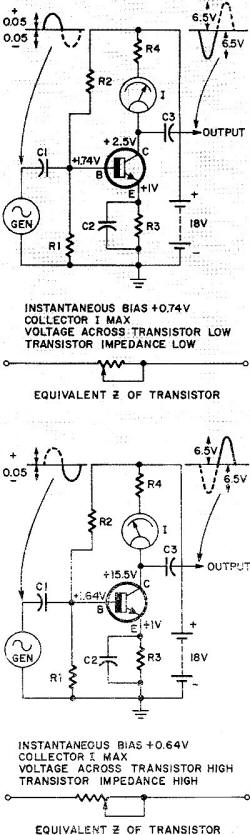

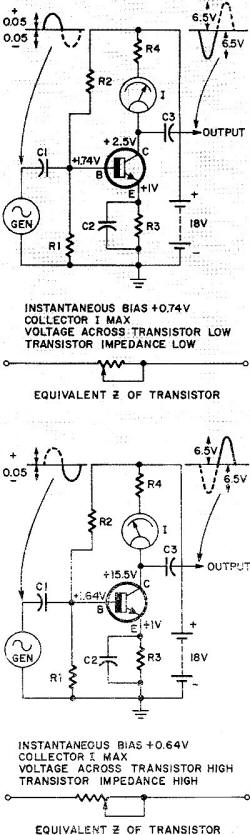

In Fig. 9-a the generator is passing through its maximum positive excursion

and is producing a peak +0.05 V. This voltage will add to the +1.69 V DC bias voltage

and cause a total instantaneous voltage between base and ground of +1.74 V. From

the curve in Fig. 8, we see that this corresponds to maximum current through

the transistor. This is indicated by the current meter connected in series with

the collector of the transistor.

The increased current through R4 causes a larger voltage drop, so that for an

instant the collector voltage drops to approximately 2.5.

The result of the negative half-cycle of the generator is shown in Fig. 9-b.

This negative 0.05-V excursion subtracts from the 1.69-V bias, so that for an instant

the voltage between base and ground is 1.64 V. The curve in Fig. 8 shows that

this corresponds to minimum collector current. The reduced current causes a smaller

voltage drop across R4 and allows the collector voltage to rise to approximately

+15.5.

From this we can see that an input signal of 0.1 V peak-to-peak can cause a collector

or output signal of 13 V peak-to-peak. Also, phase inversion occurs. The DC and

AC voltage excursions shown demonstrate amplification of the transistor. Capacitor

C2 is large enough to bypass R3, so that no AC signal is lost across this resistor.

The voltage at the emitter will reflect any average current change through the transistor.

Emitter voltage is a good indicator of transistor conduction. If this voltage is

too high, the transistor current is too high. If it is low, the current is too low.

Diode Stabilization

Some amplifiers require a different type of bias stabilization since their primary

purpose is to increase power. The circuits discussed are designed to maintain constant

current. This would defeat the purpose of the push-pull amplifier, so another method

is used.

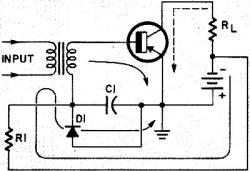

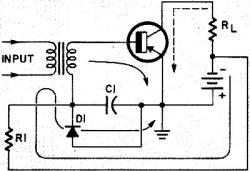

The most common stabilization method used for these amplifiers is to use bias

elements which are temperature-sensitive. One method, shown in Fig. 10, is

to use a diode made from the same material as the transistor.

Fig. 10 - Diode stabilization.

The diode is fed with a constant current through R1. The voltage drop across

the diode biases the transistor and is inversely proportional to its temperature.

In other words, as the temperature of the transistor and diode increases, the resistance

of the diode decreases and the voltage drop across the diode decreases lowering

the bias voltage the necessary amount.

Push-Pull Stabilization

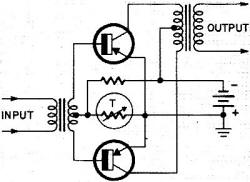

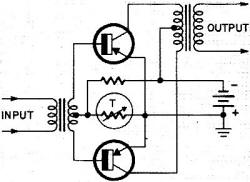

Thermistors are frequently used to stabilize push-pull output stages. Thermistors

have a negative temperature coefficient of resistance. A circuit using a thermistor

for bias stabilization is shown in Fig. 11. The current through the thermistor

is held relatively constant by the high series resistance. The voltage drop across

the thermistor supplies the actual transistor bias. Since the compensation in this

circuit is often greater than desired a parallel resistor is sometimes added to

the circuit to decrease its sensitivity.

Fig. 11 - Push-pull amplifier configuration.

Note that the purpose of the temperature sensing element is, not to compensate

for ambient temperature, but to compensate for the junction temperature of the transistor.

Consequently, whether the sensing element is a diode or a thermistor it should be

located intimately with the transistor or transistors that it controls.

Posted September 2, 2024

(updated from original

post on 12/6/2018)

|