|

This is part 5 in

a series that began in the October 1951 issue of Radio & Television News

magazine (see

part 4). Previous articles dealt with crystal diodes in AM and

FM radios, and this article shifts gears by moving into television applications.

Crystal diodes were and are still used in frequency generation, envelope detection,

frequency mixing, and AC signal rectification. Vacuum tubes could be used for the

latter three applications but many physical issues such as size, weight, power consumption,

and heat dissipation proved to be major drawbacks as designers strived to reduce

the size of electronics assemblies, make them more energy efficient, lower the cost

of manufacturing, increase reliability, and decrease weight. Demands for portability

was the motivation for much of the work. Early crystal diodes could be noisy and

fragile if not mounted carefully, but as will all technology, continual R&D

has refined and improved crystals significantly. These early articles give great

insight into the work that went into adopting and promoting a new type of device.

Crystal Diodes in Modern Electronics

A conventional i.f. transformer assembly using a 1N64 germanium

diode. G·E uses this unit in its TV receivers.

By David T. Armstrong

Part 5. A discussion of some of the applications of crystal diodes to television

receiver circuits.

In earlier articles of this series we discussed the uses of crystal diodes in

AM and FM applications. In this and the next article we will consider several of

their applications in modern television receiver circuits.

Fig. 3 shows several applications of crystals in TV receivers. As far as

it is possible to discover, no manufacturer uses crystals at all these points, but

some manufacturer uses crystals at each of these points. This block diagram indicates

the possible applications of known germanium diode crystals in modern television

receivers, based on present knowledge of circuitry and the performance characteristics

of crystals. In general, the number of germanium diodes that may be used in a given

television circuit is limited only by the number of diodes required.

To be quite optimistic, with the recent development of crystal triodes, which

may be used in place of certain vacuum tube triodes, the future is bright with possibilities

for small TV receivers that may become virtually tubeless!

Germanium diode type crystals have a definite place which they are now assuming

on a large scale. It will be well for the experimenter and technician to know something

about them for they are quite likely to supplant the 6H6's and the 6AL5's in many

TV circuit designs.

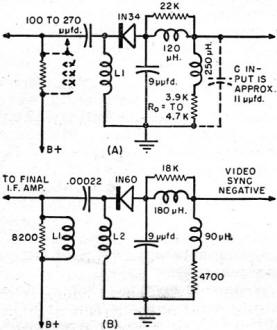

Fig. 1 - Basic TV detector circuits. (A) A series and (B)

a shunt type of circuit.

Fig. 2 - The special test circuit for the 1N64 as used by

General Electric Company.

When color comes along the fellow who knows the fundamentals of the application

of germanium crystals will be able to apply this knowledge to the uses of germanium

and silicon crystals in the ultra-high frequency color spectrum. Be ready for it.

That will be the day for germanium and silicon diodes! While eventually crystals

are likely to displace tubes at high frequencies, even at low frequencies, certain

types of crystals are proving more stable than presently available tube type diodes.

Basic Video Detector Circuits

At the present time the most widely accepted application of germanium diodes

in television receivers is as video detectors. The chief function of a video detector

is to demodulate the high frequency i.f. signal to obtain the video modulation.

The most common component used for this purpose, until recently, has been half of

a 6AL5. With but minor circuit changes a germanium diode may be substituted for

the vacuum tube as a high quality detector element.

This substitution is not a simple problem, however. It is necessary to find ways

and means of eliminating the other half of the 6AL5 vacuum tube diode in order to

dispense entirely with the tube, socket, and associated wiring. This problem has

been solved in various ways, such as using another germanium crystal as the diode

d.c. restorer, sync clipper, or a.g.c. peak detector. Of course it is possible to

design and use a full wave detector circuit using germanium diodes, but no manufacturer

seems to have done this. It is possible to design a very fine full-wave video detector,

but most design engineers feel that the improvement in greater output and higher

efficiency would not be worth the cost nor the circuit complication.

In Part 2 (November 1951 issue) both series and shunt rectifier circuits were

described. Both can be used in video detector applications. Consider the simple

germanium diode TV detector circuits shown in Fig. 1. A is a series type circuit

and B is a shunt type circuit. Both types of circuits are widely used and both will

perform equally well in properly designed systems.

The shunt circuit shown at B in Fig. 1 is used primarily when a closely

coupled i.f. transformer is used and capacitive coupling to the detector is desirable

to prevent "B+" voltages from being impressed upon the diode crystal. With the diode

crystal connected in such a shunt arrangement it provides its own d.c. return path;

this path is normally restricted by the coupling condenser in the series hook-up.

Fig. 3 - Possible applications of germanium diodes in modern

television receivers.

Fig. 4 - Rectification efficiency vs. signal level. The

curve for the 1N34 may be considered representative of the 1N60. These measurements

were made with a fixed driving impedance and voltage which is not exactly the case

in a video detector. In that particular instance the loading on the last i.f. coil

is of most importance.

For a shunt circuit the back resistance characteristic of the diode is important.

It is necessary that the back resistance be at least ten times the load resistance

to maintain the achieved gain. However, very high back resistance values may sharpen

the "Q" of the tuned circuit; then bandwidth may have to be restored by a change

in value of the coupling condenser or with a compensating choke.

For a series type circuit, such as that shown at A in Fig. 1, the forward

dynamic resistance of the diode is important since it may be so large in comparison

to the load as to form a voltage divider and reduce the output voltage. Because

germanium diodes have lower dynamic resistance than vacuum tubes, additional gain

may be realized in the crystal type video detector circuit. The "Q," or the sharpness

of the resonance of the tuned circuit, will be broader as a result of the lower

resistance of a germanium diode compared to that of a vacuum tube. While this may

reduce the gain of the last i.f. stage, it can be restored by increasing the load

resistance.

For both the series and the shunt circuit the load impedances are determined

primarily by the video bandwidth requirements; therefore, these load impedances

must necessarily be low values. The load condenser should be small enough to present

a reasonably high impedance to the highest video frequency of 4 mc. and at the same

time be sufficiently large to hold the charge from one peak to the next with a 24

mc. or 44 mc. i.f. signal. The load resistor must be large enough so as not to lower

the impedance of the condenser and small enough to permit the condenser to discharge

at video frequencies. Typical values are 5 to 10 μμfd. capacitance and 1500 to

5000 ohms resistance.

It should be realized that there are wider variations in the dynamic resistance

of germanium diodes than there are in vacuum tubes. For this reason detector type

germanium diodes are selected in the manufacturing process by test in an actual

video detector circuit, see Fig. 2. This helps assure uniformity in actual

performance. The design engineer attempts to select circuit values that minimize

individual diode variations.

As a video second detector the germanium diode must convert an i.f. of 20 to

50 mc. into d.c., with the video signal and synchronizing pulses being passed on

to the amplifier while the i.f. is rejected. This requires crystals capable of withstanding

voltages higher than 1 or 2 volts; hence types like the 1N60 and 1N64 are used because

these crystals are able to withstand voltages on the order of 5.0 to 10.0 volts.

Because both the dynamic resistance and the crystal capacitance of the germanium

diode are very low, the crystal provides excellent demodulation in video detection

circuits. The crystal provides exceptional linearity at low signal levels and is

free from any undesirable contact potential effects. The excellent linearity characteristic

of germanium diodes at low voltages and the absence of contact potential effects

help achieve improved video output with reduction of distortion factors in low modulation

regions. Hence the quality of the signal representing white is improved and the

over-all picture presents more natural rendition of various shades from white to

gray to black.

Since the picture carrier is amplitude modulated, a TV detector circuit is similar

to the detector circuit found in AM receivers. In both instances the chief function

of the detector is to demodulate the picture carrier. Crystals perform the detection

function remarkably well at the AM broadcast frequency and crystals will perform

the detection function better in TV since crystals operate better at higher frequency.

The reason for this is that the efficiency of germanium diodes does not fall off

as rapidly as the efficiency of tubes with an increase in frequency at which the

circuit is operating. But a video detector imposes more severe requirements on the

detector diode than an AM broadcast type detector or an FM receiver type detector

is called upon to meet.

The trend in video detector design has been from the 6H6 to the 6AL5 to the germanium

diodes. The input signal to the detector is such that current flows through the

diode when the diode plate is positive with respect to the cathode. While the polarity

of the picture signal is essentially a design problem and not a service problem,

it must be remembered that whenever a germanium diode is replaced in a TV receiver

the original polarity must be maintained, otherwise white and black objects will

be reversed and synchronization will become extremely critical.

In general, picture phasing considerations are the same for a vacuum tube diode.

It is necessary to achieve correct polarity of the crystal diode according to whether

the blanking pulses are negative or positive and whether the signal injected to

the CRT is to the grid or to the cathode. When the signal is to the grid it must

end up with sync negative; when the signal is to the cathode, it must end up with

sync positive. Whether the sync will be positive or negative depends upon the number

of video amplifiers and the polarity of output of the detector; there is a phase

shift of 180 degrees for each video amplifier.

Detector Circuit Considerations

Many modern TV receivers use a germanium diode as the video detector for various

reasons as listed below:

1. Simplicity of design,

2. Ability to handle a large dynamic signal range,

3. Minimum amplitude distortion (not too important, but worth mentioning),

4. High degree of linearity,

5. Ability to shield the detector by mounting inside shield can.

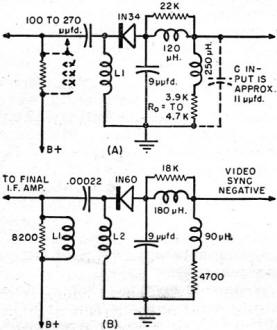

Fig. 5 - Series type video detectors. (A) Using the 1N34.

The inductance, L1, is tuned to the i.f, frequency with the total shunt

capacitance. If the tuning coil is on the plate side of the circuit, L1

is a 10 μhy. r.f, choke. (B) Using a 1N60. Either L1 or L2

may be the tuning inductance. The value should be about 0.3 μhy. When tuning inductance

L1 is on plate side of tube. L2 should be a 10 μhy. r.f. choke.

One important requirement of a video detector is that the output level be approximately

flat for frequencies from 30 cps to 4.0 mc.; the video amplifier should be designed

to pass this range of signal without attenuation. Therefore, the value of each component

in the detector circuit is usually the result of careful selection by the design

engineer; if replacement of any component is necessary, a technician should be careful

to use resistors, condensers, and coils of the same value. The coupling network

may be of the peaking coil resistor type, or it may be a low pass filter type. Many

receivers are now using a low pass filter type. It is worthy of note that no d.c.

restoration is necessary with direct coupling from the video detector to the video

amplifier because the d.c. component is preserved with direct coupling. But there

must be direct coupling all the way from the detector circuit to the picture tube.

The signal at the output of a video detector is not quite strong enough to drive

a picture tube. In this respect it is similar to AM receiver detectors which require

one or two stages of audio amplification for satisfactory sound. Video amplifiers

following the detector are usually RC amplifiers similar to those found in AM receivers.

Signal amplification following the detector is generally small because most of

the receiver video gain is obtained in the i.f. strip. While it is possible to have

two stages of video amplification after the detector, it is common practice to simplify

the circuit by using just one stage of d.c. coupled video amplification. This means

that a detector must cover a wide range of signal amplitudes from 0.5 to 5.0 volts.

The 44 mc. i.f. frequencies may involve some reduction in predetection gain (although

with tubes like the 6BC5 and the 6CB6, the gain at the higher frequencies is greater

than was thought possible); thus, the detector may be called upon to work efficiently

at low signal levels and high frequencies. The video detector for such a circuit

would have to provide good linearity at low signal levels so that correct over-all

highlight gamma (a numerical indication of the degree of contrast in a received

television picture) may be maintained.

The video detector may be any of the usual types such as half-wave, full-wave,

plate circuit, grid leak, or infinite impedance type. By virtue of simplicity the

diode detector is so common that it is used almost exclusively; practically all

are of the half-wave type. The additional circuit complication for full-wave detection

does not warrant the expense involved.

Detector rectification efficiency of a typical half-wave diode tube type video

detector circuit might be on the order of 35-40%, that is, with an i.f. input voltage

of 1.4 r.m.s. to the diode the video output is on the order of about 1.5 volts peak-to-peak,

or from maximum white to synchronizing pulse tip. The detection efficiency of a

germanium diode type video detector circuit may approach about 52%. Small time constant

load circuits involving small capacitances and low values of load resistance are

necessary in order to preserve the high frequency video components in the detector

output; these affect rectification and account for some loss in over-all efficiency.

Fig. 6 - Video bandpass curves. The curve for the 1N60 would

be the same as that shown for the 1N34. The shape of the bandpass curves is more

dependent on the load circuit values than on tube or diode used.

Fig. 7 - Static diode characteristics graph. Note that the

curve for the 1N34 and the one for the 1N64 qo through the zero point for voltage

and current on the graph and that the 6AL5 draws some current at the point of .zero

volts applied potential.

Fig. 8 - Sylvania's test circuit for the 1N60.

Fig. 9 - (A) Series type 1N64 video detector. (B) A shunt

type 1N64 video detector. (C) A commercial type video detector as used by Calbest

Engineering and Electronic Company.

Fig. 10 - Circuit of the Garod Series 101A, 101B, 101C,

101D, 103, 103A, and 105 using a germanium crystal as a video detector and a diode

load resistance of 8200 ohms.

Fig. 11 - The Teletone TAP-2-UL chassis.

Fig. 12 - The Freed-Eisemann Models 101, 102, 103, and 104

use this circuit as the fourth video i.f. stage.

Because these remarks may seem misleading to some engineers it should be understood

that they are made with the following considerations in mind. The term "rectification

efficiency" does not indicate whether or not more useful video output will be obtained

by germanium diodes than by tubes. It is necessary to design the circuit specifically

for crystals or tubes in order to maintain proper bandwidth as well as a.c. output.

If two optimum circuits are compared there is likely to be little difference in

output for crystals over tubes.

There seems to be no disagreement that the germanium diode has decided advantages

over a vacuum tube where the detector is required to operate with signal levels

on the order of 0.5 volt peak or less. For a bandwidth of 4.0 mc. the germanium

crystal 1N34 shows a 5.5 db gain over a 6H6 and approximately a 0.5 db gain over

a 6AL5 at a signal level of 5 volts. See Fig. 4. A 1N60 will show slightly

better gain. Small signal rectification of the crystal diode for low values of load

resistance is much better than for the 6AL5.

Fig. 5A shows a video detector circuit using a 1N34 type crystal. The resistor

in series with the 250 μhy. coil and ground may vary from 3900 to 4700 ohms. The

performance of the circuit is better when the resistor is 4700, as shown in the

comparative sets of curves in Figs. 4 and 6. These curves are more dependent upon

load circuit values than upon tubes or crystal, diodes.

Because of the great interest in the use of germanium diodes in modern television

circuits newer and better types of crystals are being designed and manufactured.

Fig. 5B illustrates a Sylvania type video detector circuit designed especially

for television applications. The type 1N60 was specifically designed and is tested

for this type of service in the circuit shown in Fig. 8. This germanium diode

provides high circuit efficiency and exceptionally good linearity at low signal

levels. Low interelectrode and stray circuit capacitances make for improved video

response. Increased over-all gain is obtained by virtue of reduced capacitive loading

of the detector input circuit. When a circuit is designed with the component values

specified, a full 4 mc. video bandwidth may be maintained at the output of the detector.

This circuit has high dynamic efficiency, low shunt capacitance, and excellent

linearity at low signal levels of 0.5 volt peak or even less signal voltage.

For preservation of the high frequency video components in the demodulated picture

carrier envelope the time constant of the vacuum tube detector load circuit should

not exceed approximately 0.08 microsecond. This time constant should be observed

even with elaborate types of high frequency compensation networks. To achieve this

time constant the diode load resistance is generally 4000 ohms or less, and the

load capacitances are correspondingly small. It is for these reasons that the efficiency

of a vacuum tube detector circuit is generally low.

The dynamic impedance of the diode is an appreciable portion of the total circuit

impedance. With the 1N60 germanium diode there is a substantial improvement in detection

efficiency because the dynamic impedance of the crystal is materially lower than

that of an equivalent vacuum tube diode of the 6H6 or 6AL5 type. Since with a crystal

the shunting capacitance is substantially less it is possible to increase the effective

load resistance without sacrificing bandwidth.

Increasing the diode load resistance results in material improvement of the over-all

detection efficiency. The circuit in Fig. 5B has been carefully designed to

provide a bandwidth of not less than 4.0 mc. The component values have been chosen

to work into an effective load capacitance of about 11 μμfd. The 9 to 10 μμfd. condenser

should be a low tolerance component, or the tolerance should be on the low side

rather than the high side so that the capacitance does not exceed 10 μμfd.; the

additional 1 or 2 μμfd. is the shunt capacitance of the germanium crystal.

In this circuit the detector polarity is such that the demodulated video signal

at the grid of the video amplifier is sync negative. There are good reasons for

recommending this type circuit:

1. There is some noise limiting in the video amplifier by virtue of driving the

tube to cut-off on the noise peaks.

2. The use of a d.c. coupled video amplifier between "the detector and the picture

tube preserves the d.c. component and eliminates the necessity for d.c. restoration.

It is better to retain the d.c. than to block it with a condenser and then attempt

to restore it.

3. This circuit presents a high quality picture with receiver simplification.

4. The use of the 1N60 provides improved response in the direction of white,

better background illumination levels, excellent highlight detail, and improvement

in the over-all gamma of the video system.

Fig. 7 shows static characteristics for the 6AL5, 1N34, and the 1N64 over

a small voltage range near the origin of the curves. The following aspects of this

graph are noteworthy:

1. The linear portion of the crystal curves extends to considerably lower voltage

signal levels than the 6AL5 is able to achieve.

2. This improvement in linearity at low signal levels has the over-all effect

of improving highlight detail.

3. The better the linearity the more reduction of amplitude compression in the

direction of a white signal.

4. For small value signals, rectification efficiency of crystals is better with

low values of load resistance than with any comparable 6AL5; it is possible to use

higher load resistances with the crystal without sacrificing any element of picture

quality.

Circuit Applications of the 1N64

General Electric has developed a special second detector diode, the 1N64. This

was designed specifically for use as a second detector in television receivers.

The physical characteristics of this diode are identical to those of the general

purpose types. It is primarily selected for maximum efficiency as a detector at

high frequencies because only in this way can proper detection and uniformity be

assured. The minimum d.c. output current in the circuit of Fig. 9B is 100 microamps,

the peak inverse voltage is 20 volts, and the maximum shunt capacity is 2.0 μμfd.

In addition, to assure uniformity of bandwidth, the diode is tested to have more

than 50,000 ohms resistance at -1 volt and less than 4000 ohms resistance at +0.25

volt.

The schematic shown in Fig. 9B was designed to use a 1N64 germanium diode

with the 44 mc. i.f., and this is the circuit used in most G-E model television

receivers. The small size of the diode makes it possible to mount it inside the

last i.f. can for maximum shielding. The 1N64 provides optimum efficiency in this

shunt type detector circuit. The circuit components, 9 μμfd. condenser and

the 31.5 microhenry coil, may be varied if it is desired to change the bandpass

characteristic. Similarly, variations of the 5 μμfd. condenser and the 3600 ohm

resistor will affect the video output as a function of the video frequencies.

Fig. 9A shows a series type detector circuit in which the low forward dynamic

resistance of the 1N64 enables it to perform exceptionally well. Since any variation

of the forward resistance of the diode will effect changes in the bandpass characteristic

of the detector stage, the load resistance should be maintained relatively high

with respect to the dynamic forward resistance of the diode for the purpose of minimizing

variations in the bandpass. For this reason the components should be chosen with

great care. Low tolerance values will stabilize any crystal diode detector circuit.

Because of the great interest in the use of germanium crystals as video detectors

a number of commercial applications of the basic circuits discussed have been illustrated.

Fig. 9C is an application of the 1N64 to a TV receiver by the Calbest Engineering

and Electronics Company. For convenience, the associated circuitry, involving a.g.c.,

contrast, and a video amplifier is presented.

Teletone has been interested in TV receiver simplification because they are designing

and manufacturing low price budget sets for a mass market. Fig. 11 shows a

Teletone circuit using a crystal with an absolute minimum of associated components.

The use of a resistor with a value of 5600 ohms would not be possible with a 6H6

or a 6AL5 because the bandpass would be unduly affected.

Garod makes excellent use of a germanium crystal with a relatively high value

diode load resistance of 8200 ohms. This is one of the highest values found in any

of the commercial circuits available. This is also an excellent example of a video,

detector feeding a two-stage video amplifier with a single tube, see Fig. 10.

Note also the use of the 1N64 between the second video amplifier stage and the picture

tube. The 1N64 was selected for specific d.c. characteristics for this circuit;

it helps eliminate hash in the sync circuit.

In the Freed-Eisemann circuit of Fig. 12 there is a complete schematic for

the fourth picture i.f., the crystal video detector, and the first video amplifier.

This is a quality circuit and it follows the standard recommendations for the choice

of the component values, as indicated elsewhere in this article. While this circuit

uses the 24 mc. i.f., it will work equally well with the 44 mc. i.f. and with a

signal input voltage of 0.1 r.m.s.

(To be continued)

Posted June 8, 2022

(updated from original post on 12/21/2015)

|