|

Electronics hobbyists are always

anxious to hear the announcement of a new device that is forecast to revolutionize

the tech world. In the late 1950s something as relatively tame as a crystal photocell

satisfied that urge. This 1957 article in Radio & Television News magazine

is a prime example. Today it takes something like a negative refractive index metamaterial

to invoke the same sense of awe and wonder. Those were simpler times, but then again

even today's beginners in the world of electronics circuit designing and building

have to start somewhere, and these types of circuits are as good as any place.

Crystal Photocell Circuits

By Allan M. Ferres

The development of this tiny, light-sensitive cell makes possible an interesting

variety of compact control units.

The photoelectric cell is a most interesting subject for the electronic experimenter.

When connected to relays, the number of uses to which it can be put is limited only

by the ingenuity of the experimenter. It can be used for such diverse applications

as announcing a patient in a doctor's waiting room, turning on house lights and

advertising signs at dusk, automatically opening and closing doors, warning householders

of intruders, preventing shoplifting, etc. The list seems almost endless, but may

now be even further extended with the development of the crystal photocell.

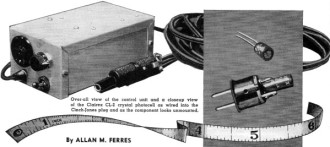

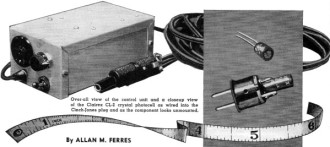

Overall view of the control unit and a close-up view 01 the Clairex

CL-2 crystal photocell as wired into the Cinch-Jones plug and as the component looks

unmounted.

This tiny cell has several advantages over the high vacuum and gas-filled tubes

usually employed in photoelectric relay circuits. Its characteristics are such that

light-controlled relays may now be used in applications which are impractical with

the conventional photoelectric tubes.

The crystal photocell is a very small device about the size of a lead pencil

eraser, 1/4" in diameter and 1/2" long. The light sensitive element is a pure cadmium

sulphide crystal which responds to light over the entire visible spectrum. The crystal

is a semiconductor, its resistance decreasing with an increase in light intensity.

Its electrical characteristics are such that it may be operated at a considerable

distance from the associated amplifier and relay. This factor and its small size

make it ideal where concealment of the device is desirable, or where space is limited.

The crystal is so sensitive that operation is practical with normal room illumination

when used with a simple amplifier. This eliminates the necessity for using special

exciter lamps and optical equipment. In some applications, the relay may be operated

directly by the crystal itself. Its low cost and mechanical ruggedness make the

crystal photocell an ideal device for light-controlled relay experiments.

This article describes a control unit using a simple, basic photocell amplifier

and relay circuit. Four other circuits are also discussed which will be of interest

to experimenters.

The basic circuit, shown in Fig. 1A, is sensitive enough to operate at one-tenth

of a foot-candle of light. A protective resistor, R1, the crystal photocell,

the Clailrex CL-2, and the variable load resistor, R2, are connected

in series across the 117-volt a.c. line. C1, which shunts the load resistor,

charges to peak voltage on each cycle to provide a higher striking voltage for the

thyratron. The miniature thyratron, its current-limiting resistor, R3,

and the relay are also connected across the line through the switch S1.

The relay is a plate-circuit type having a coil resistance of 5000 to 8000 ohms

and an operating current of not more than 6 milliamperes and provided with s.p.d.t.

contacts. C2 shunts the relay coil to prevent chattering. The light,

bell, or other device to be operated plugs into receptacle SO1. As a

photocell relay is usually operated continuously, no a.c. "on-off" switch is included,

but, of course, one may be added if desired, in series with the line cord.

Fig. 1 - Five practical circuits using the Clairex CL-2

crystal photocell. (A) Basic circuit which will operate at 1/10th footcandle. (B)

Variation of basic circuit in which power is furnished to the output receptacle

when light falls on cell. (C) Circuit for operating lighting sequences. (D) Circuit

for high speed operation at low illumination levels. and (E) A simple setup to be

used as "intrusion" alarm.

Overall view of the photocell unit. It is built into a 2" x 3"

x 5" case. The placement of parts is non-critical as there is no heating. CL-2 unit

is at right.

The starter anode of the 5823 thyratron obtains its voltage from the voltage

divider made up of R1, the crystal cell, and R2. When the

cell is dark, its resistance is high and the starter anode voltage is too low to

allow the thyratron to draw plate current. When light strikes the cell, its resistance

drops, increasing the voltage across R2, and the tube conducts. With

the switch on, the relay contacts are wired so that the line voltage is connected

to the output receptacle only during the interval of time when the light on the

cell is interrupted. When the switch is off, a momentary interruption of the light

will remove the plate voltage from the thyratron and power will be furnished to

the receptacle continuously, even though the light to the cell is restored. This

locking type of operation is desirable when the device is used to sound an intruder

alarm bell.

As shown in the photographs, the necessary parts can be easily mounted in a 2"x

3" X 5" case. No ventilation of the case is needed as the power dissipated in the

unit is less than one watt. The placement of the parts is not at all critical, so

any convenient arrangement may be used. Socket terminals 2, 5, and 6 of the 5823

should not be used as tie points as these pins are used for internal connections

in the tube. The crystal photocell is wired into a Cinch-Jones type P-302-FHT plug.

A matching receptacle is mounted on the case, so that the cell can be either attached

to the case or used at a distance of 20 feet or so from it by means of an extension

cord.

Ordinary lamp cord is adequate for this purpose, provided that its insulation

is good, as leakage between the conductors will reduce the sensitivity and may cause

erratic operation. The cell can be shielded from stray illumination by a short length

of cambric tubing.

The unit is put into operation by turning switch S1 to "on," plugging

the line cord into an a.c. outlet, and pointing the photocell toward a source of

light. R2 is adjusted so that a steady blue glow appears in the thyratron

and the relay pulls in. Cutting off the light to the cell will cause the blue glow

in the tube to disappear and the relay will drop out. The adjustment of R2

is not critical, except with very low levels of illumination. Line voltage variations

will have little effect on the operation of the unit.

Fig. 1B is similar to the basic unit except that power is furnished to the

output receptacle when light falls on the cell, instead of when the cell is dark.

The switch must be set to "on" for locking operation. The only additional part required

is R4 a 1-megohm, 1-watt resistor which is wired to hold the tube in

conduction when the relay pulls in. This circuit might be used to open a gate or

garage door when the car's headlights illuminate the cell.

Fig. 1C is a good circuit to use to turn on signs or lights at dusk, and

to turn them off again at dawn. The cell load resistor is divided into two parts,

and an additional set of relay contacts is used to change the value of the load

when the relay drops out. This modification of the circuit is desirable to insure

positive operation of the relay at the time of day when the light is slowly fading

down to the operating value. R5 must be adjusted first so that the relay

pulls in, turning off the artificial light at the desired amount of daylight, and

then R6 is adjusted to turn on the light at dusk. The photocell must

be shielded from the artificial light, or the light will blink on and off in a form

of oscillation.

Fig. 2 - Average characteristics of the Clairex Type CL-2 crystal

photocell. See article.

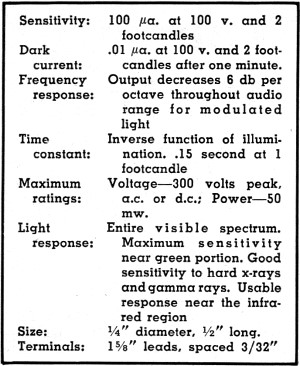

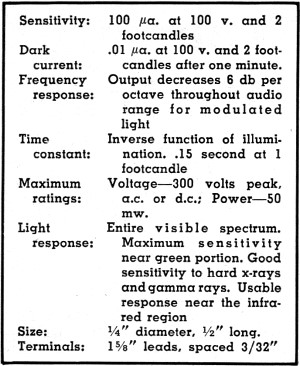

Table 1 - Specifications on CL-2 photocell.

The circuit shown in Fig. 1D is useful when high speed operation is required

at very low illumination levels. The value of cathode capacitor, C4,

depends upon the amount of light available. For .1 footcandle, C4 should

be 100 µfd. and for 1 foot-candle, 10 µfd. is adequate. 150-volt capacitors

should be used. If fast recovery from an overload of light is necessary. R7

must be shunted by capacitor C3, its value being determined experimentally,

under actual operating conditions. The relay pulls in when the cell is exposed to

light and drops out when the cell is dark. The wiring of the output receptacle is

governed by the type of operation required. V2 may be either a 6C4 or

a12AT7 with the sections connected in parallel. Higher operating speed is obtained

with the 12AT7 The relay must be capable of fast operation to take full advantage

of this circuit. In some applications, a counter may be used in place of the relay.

A simple circuit which will sound a chime when someone enters a doorway is shown

in Fig. 1E. For the direct operation of the 1 milliampere relay, a light intensity

of 40 to 50 foot-candles is required. This can be conveniently obtained by placing

a 25-watt lamp on the same side of the doorway as the photocell and reflecting its

light into the cell with a magnifying mirror placed on the opposite door jamb. A

shaving mirror is suitable for this purpose. A small magnifying lens should be mounted

in front of the cell, focused to obtain maximum relay current. When the light on

the cell is interrupted by someone entering the doorway, the relay will drop out

and the chime, plugged into SO1 will sound.

Many other circuits and applications will occur to the experimenter as he works

with light-sensitive cells. The graph of Fig. 2 and Table 1 provide a useful

guide to the operating characteristics of the Clairex CL-2. When working out other

circuits, care should be taken not to exceed the 50-milliwatt power rating of the

cell as operation tends to become unstable above this point.

The service technician might well be able to add to his income by building and

installing light-operated equipment in stores, doctors' offices, machine shops,

etc. Building the basic unit described in this article, or one of the other circuits,

is a good way to get started toward designing commercially profitable devices. In

a more frivolous vein, they can be worked into some amusing parlor tricks.

The Clairex type CL-2 photocell is available from the Allied Radio Corporation,

100 North Western Avenue, Chicago 80, Illinois; Sun Radio and Electronics Company,

650 Avenue of the Americas, N. Y. 11, N. Y., and from the Clairex Corporation, 50

West 26th Street, New York 10, New York. The net price is $3.50.

The author wishes to thank Mr. Al Deuth of the Clairex Corporation for his cooperation

in providing data necessary to the preparation of this article.

Posted April 5, 2021

(updated from original post on 6/21/2013)

|