|

May 1946 Radio News

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Radio & Television News, published 1919-1959. All copyrights hereby

acknowledged.

|

By 1946, radio and television manufacturers

were scurrying to supply the huge, pent-up demand for communications and entertainment

systems that accumulated during World War II. Fortunately, the dearth of electronics

components, raw materials for chassis fabrication, and available labor was suddenly

and significantly turned around by late 1945. Wanton destruction of entire cities

in Europe left citizens without many basic creature comfort items like radios, televisions,

refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, toasters, automobiles, and other things taken for

granted a decade earlier. As with any well-executed plan, manufacturers endeavored

to survey the market demand for such products and then devised a way to satisfy

that demand. Radio News magazine published a synopsis in mid-1946 of the

state of the radio and television industry in Europe so that companies in both the

U.S. and in Europe could gauge the effort that would be required.

Report on the European Radio Industry

By Leon Laden By Leon Laden

London, England

United States manufacturers, anxious to evaluate the absorption capacity

of overseas markets for their postwar production outputs, are presented here with

a factual and up-to-date picture of Europe's present-day supply and demand position

in the radio and television field.

In Europe, as much as in the United States, manufacturers of radio equipment

are making prodigious efforts to catch up with accumulated demands for domestic

radio and television receivers created by the long years of scarcity.

But while the volume of American radio production is slow in starting it may

by the end of the year reach a staggering total (completed units) topping the 10

million mark recorded for 1939.1 The necessarily incomplete figures available

for measuring, with any degree of reliability, the current output of European radio

production leave but little doubt of its utter incapacity to surge ahead and approach

the comparable figure of 8 million receiving sets.

This divergence in the respective levels of output between the U. S. and European

radio production is partially accounted for by the disruption of all types of civilian

production due to hostilities, and the overriding needs for housing, food, clothing,

and other necessities.

At the same time, however, it is also due in part to the fact that the American

radio industry is a highly concentrated and efficient industry with an enormous

home market, while the European radio industry, dispersed over many countries and

forced to purchase parts in a closed market from firms with a monopoly position,

is one of the most woefully backward and grossly inefficient industries in existence

over here.

The Philips' factory at Eindhoven, Holland. Before the war this

plant produced a high percentage of the European radio tubes.

In fact, according to investigations conducted recently by Ian Mikardo, a well-known

British production expert and member of Parliament, European radio production costs,

despite considerably higher American wages, are invariably well above those in America,

but comparable manpower efficiency figures average out nearly five times lower in

the U. S. than in Britain, eight times lower than in France and much lower still

than in Russia.

Of course, the economic utilization of labor cannot be regarded as the sole criterion

of industrial efficiency and figures comparing output per operator, necessarily

and admittedly compiled on the basis of approximations and conjectures, must be

taken with a good many reservations even in an industry such as the radio industry

where undoubtedly a high proportion of the final production cost is represented

by labor cost.

In particular, it must be borne in mind that the American radio industry managed

to increase its output per operator-hour through the installation of special mass

assembly line machinery, geared to produce enormous quantities of standardized midgets,

car radios, pocket radios, portable radio-phonographs, personal portables and similar

items which are of a design, size and shape less cumbersome to make and offering

greater economy in production than table and console models which are principally

in demand in Europe.

Moreover, apart from the quantity of sets turned out per operator, quality, durability

and the differing marketing conditions operative in European countries must also

be taken into consideration. If this is done, it might appear perhaps less inefficient

than sometimes assumed to make receivers that take longer to construct but strike

a balance between production requirements and the consumers' demand for radios lasting

longer and needing less repair or maintenance.

Nevertheless, it is fully realized over here that if the radio industries of

the various European countries wish to take the brake off production and hold their

own against outside competition, their efficiency levels will have to be raised

substantially and slackness, incompetence, obsolete plant or outdated methods done

away with.

That this is generally understood is evidenced by the present planning trend

sweeping the continent and changing the traditional production patterns of its industries.

This trend, engendered, guided and financed by the governments of most of these

countries, notably Britain and France, aims at creating centralized, state-controlled

agencies canalising the allocation of factory floor-space, stocks of machine tools,

raw materials, labor and capital investment to manufacturing groups producing drastically

reduced types of standardized and stereotyped models from single factory units.

Comparison Between U. S. and European Standards

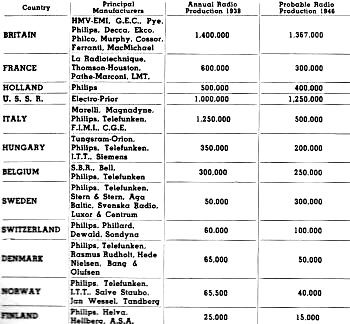

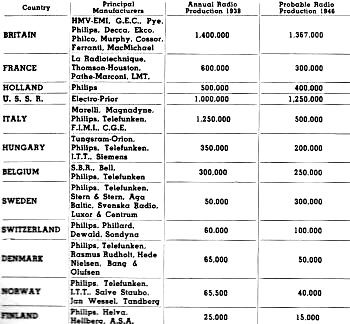

These comparative production figures for radio receivers are

indicative of Europe's 1946 production potential as compared to their pre-war output.

In a way, this continent is effectively enlarging upon a trend of production

policy which originally started at the time of the American invasion of the European

radio market after the economic crisis of 1930, when such U. S. manufacturers as

HMV, Philco, and I.T.T. established branch factories overseas, and the U. S., due

to her superior production facilities, began to exercise a rapidly growing influence

on European radio production standards by providing the lion's share of radio importations

in the different countries. This resulted in U. S. receiver construction ideas,

methods, and techniques being studied and copied so assiduously and faithfully over

here that it is hardly possible nowadays to discern any marked difference between

domestic radio sets manufactured in the U. S. and in Europe; especially since new

developments on one side of the Atlantic have always been followed, almost immediately,

on the other side, producing in time a uniform design and construction pattern irrespective

of the country of origin.

Obviously, there do exist salient features distinguishing radio sets made in

either of these two hemispheres, conditioned as much by the differing transmitting

facilities (with one or two exceptions, all European broadcast transmitters are

state-controlled or semi-state-controlled) as the different listening habits of

the public. These features, however, can be summarized as being primarily related

to practical issues and, apart from comprising such minor internal layout and build-up

differences as the presence or absence of tuned high frequency bands, the number

of intermediary stages or the sizes of loudspeakers, concern the more exacting requirements

of European listeners for outward appearance, safety of operation and length of

service as opposed to the American listeners' demand for ease of operation, accessibility

or streamlining.

Especially the "life" expectancy of sets are different over here, and a European

invariably expects a receiver, once bought, to give satisfactory service for a period

of time varying from anything up to eight or ten years, while the U. S. citizen

normally is accustomed to discard his radio after a couple of years of service,

and then replace it with a more up-to-date model.

In contrast to the American public, people in Europe are averse to investing

in eye-catching or ornamental receivers and are against buying radios with frequency-numbered,

clock-like scales, as well as being almost totally indifferent about internal construction

or tube types. Again, push-button and remote-control refinements and similar gadgets

are hardly of the same commercial value in attracting the dilatory radio purchaser

in Europe as in the States. Rather, of far greater and more decisive importance

is the possibility of using a second loudspeaker, the provision for waveband changers,

adaptability to different current supplies, a linearly arranged scale with readable

station names, a housing built in good taste architecturally, and the color of the

cabinet.

Europe's Manufacturing Potential

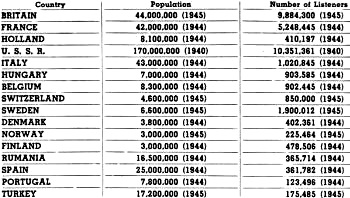

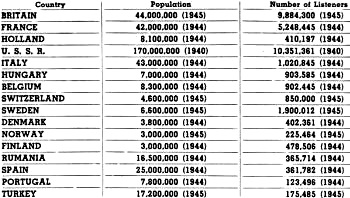

Breakdown of European population, by country and number of radio

listeners.

Estimated 1946 television receiver production as compared to

the number of sets in operation pre-war. Figures available for only those countries

listed.

European map broken down into four distinct areas (East, South,

North, West). Radio receivers designed to be marketed in each of these areas must

meet certain specific economic as well as technical requirements in order to be

acceptable to the populace.

The state in which the respective radio industries of the European Continent

find themselves today differs, naturally, with the differing political, social,

economic or industrial conditions existing in the countries in which they are located.

Thus, for example, the once powerful German radio industry, which at one time

claimed to have provided 75 percent of Germany's population and approximately one

quarter of that of the rest of Europe's listening public with radios, and the less

substantial and efficient Italian and Hungarian radio industries have all three

made their exit for the time being.

On the other hand, vigorous radio industries, capable of ministering to their

own needs on an almost self-supporting basis, have sprung up during the war in some

countries, once almost entirely dependent on foreign importations, i.e., Switzerland.

A worthwhile radio industry has been created in Sweden, a country with a long

tradition in the manufacture of low-current apparatus, and is now making speedy

headway as an exporter, on a limited scale, to other Scandinavian countries like

Norway, Denmark and Finland, in which special safety regulations prohibit the sale

to the public of sets not officially approved.

In predominantly agricultural countries and countries in which the general process

of industrialization still remains in its infancy (Czechoslovakia, Poland, Rumania,

Yugoslavia, Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece or the two countries on the Iberian Peninsula,

Spain and Portugal), the pre-war picture has hardly changed at all and radio production,

virtually non-existent before the war, has not materially developed beyond the original

stage of making crude crystal detectors of the cat-whisker type and simple amplifying

devices.

Great Britain

Of all these countries, Great Britain is probably the most important radio manufacturing

country in Europe today with the largest number of receivers per capita and a manufacturing

potential which, increased proportionally with war-time demands and based on a home

market expanded to 10,000,000 sets, is qualitatively, as well as quantitatively,

fully geared to compete for the $480,000,000 worth of radio and television purchases

and re-placements this country will need during the next five years, according to

Sir Raymond Birchall, Director-General of the British Post Office.

Moreover, Britain's radio equipment manufacturers, who once exported their surplus

output principally to British Dominion and Empire countries, and neglected or paid

very little attention to the possibilities of marketing in Europe, are today making

a determined bid to capture a fair share of the continental market with cooperatively

produced, commercially profitable, radios and a coordinated export merchandising

policy supplemented by improved overseas marketing.

It certainly looks as if the British radio exporters mean business, because at

a time when nearly every set in the country needs a repair of some kind and BBC

estimates show that 1,300,000 receivers are completely out of commission and 2,500,000

partially inoperative, the British Board of Trade has announced. that of the 1,367,000

radios which are scheduled to be made by the end of 1946, 878,000 will be earmarked

for the home market and 489,000 exported as against the average annual output of

1,400,000 sets before the war of which 66,000 only were exported.

Presumably with an eye on this market there are now rolling off British production

lines well proportioned medium-class, push-buttoned table sets with carefully arranged

amplification stages, excellent tonal output and well-matched loudspeakers; more

expensive cabinet type receivers with automatic recorders and record players; as

well as low-priced, multi-band superhets of restricted range. Invariably, these

new models contain improved tubes, components and frequency-stabilized tuned circuits

and are housed in plastic cabinets.

The prices charged for these radios are at present between 25 and 30 percent

above pre-war levels but decreased production costs, combined with design simplifications,

are expected to bring down overhead expenses and make them available to Europe's

lower income groups.

France

In spite of an almost equal population, France's listening public is way behind

Britain's and her radio industry - today gradually recovering from the effects of

the war - smaller and less organized.

This is due mainly to the fact that the French radio industry - apart from such

Dutch, American or British controlled concerns as La Radiotechnique, French Thomson-Houston

or Pathe-Marconi - consists literally of thousands of independent workshop-like

factories making custom-made receivers differing in little else but scale formations

and similar minor details.

In order to put this radio industry on a sound basis, a comprehensive plan has

been worked out and is now being brought into operation under the patronage of the

French Government's overall industrial $800,000,000 "Plan Council" scheme, entailing

the rejuvenation of the industry within five years through the concentration of

its manufacturing potential in groups of factories that will make strictly standardized

sets of a limited number of types. To satisfy the taste of the French, renowned

for their individuality and reluctance to uniformity, a small number of radios will

continue to be imported from abroad.

It is estimated that during the five years' period, a target figure of 6,000,000

sets will be reached, and the 1938 output within two years.

The cost of these receivers will probably be, in the initial stages, higher than

before the war due to higher wages, increased raw material prices and inflated overheads.

Holland

With its international ramifications in Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Hungary,

Sweden, Finland and most other European countries, as well as branch factories in

the U.S.A., Australia, Argentine, and elsewhere, the Dutch Phillips concern of Eindhoven,

has undeniably contrived to make Holland, in spite of its physically limited home

market, one of the most important radio manufacturing countries in the world.

Still hampered by lack of essential raw materials, a depleted labor force and

the destruction wrought to buildings and machinery, the Eindhoven works, the biggest

of its kind in Europe, is today swinging into production at a steep pace and probably

soon will have reached pre-war levels of output.

The Soviet Union

Sprawling across nearly one-sixth of the world's land surface, a sweep of the

earth containing all the raw materials required for the production of radio equipment,

the U.S.S.R. occupies a special position among Europe's radio manufacturing countries,

due as much to her geographical location as to the fact that the Russian radio industry

is conducted along strict state-monopoly lines.

At present, this relatively small industry is concentrating on the mass production

of single-band, 3 tube, straight receivers, 4 tube, 3 band, t.r.f. sets and 4 tube

superhets, all housed in wooden cabinets. Technically, these radios follow American

construction and layout more than European and tubes and components are usually

either direct copies produced in the country under license or else adaptations of

other versions.

Measured in relative purchasing power, prices of sets are rather high just now,

due to the supply lagging far behind the demand, and despite enormously increased

production programs for the future, will continue to be so until more pressing needs

are met and a measure of normality has returned to this Nazi-seared country.

Television in Europe Today

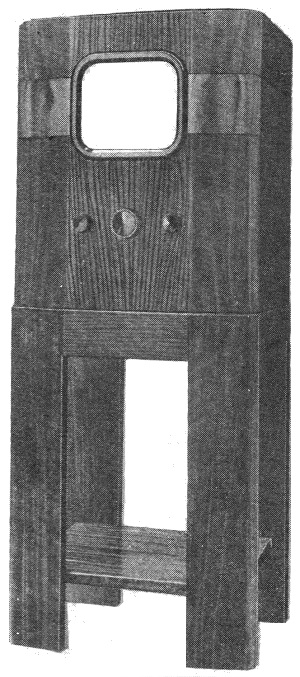

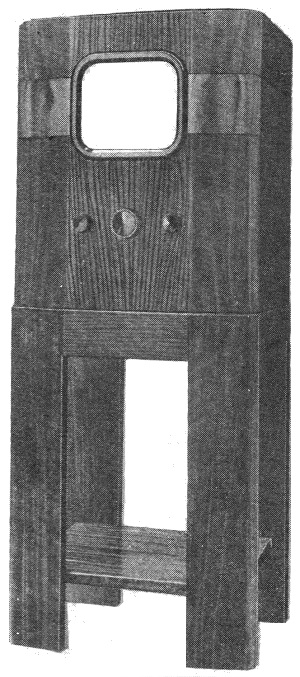

Television adapters of the type popular in England. Ordinary

broadcast receivers are used in conjunction for the sound.

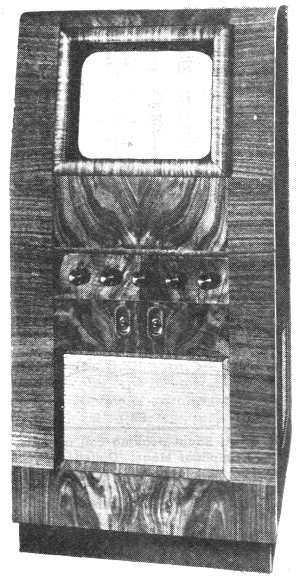

A modern British television receiver.

Complementary to manufacturing sound broadcasting equipment, the European radio

industry, like the radio industry of the U.S., early embarked upon the making of

domestic television receivers.

Of all European countries, however, Great Britain alone maintained regular television

transmissions, relayed to some 20,000 set-owners, before the war; neither France,

Germany, Russia nor Italy could claim similar services at that time and the number

of sets in operation in any of these countries never rose above 10,000.

The position is not materially changed today, and Britain is still well in advance

of other countries in the manufacture of television receivers as her manufacturers,

fully awake to the dangers of being scooped in the international television markets

by post-war competition, at an early date carried out the preliminary spade work

necessary for putting into production the blue-printed prototypes of the models

now coming into the market at the rate of a few dozen at a time. It has been confidentially

estimated that even present acute shortage of cathode-ray tubes will not prevent

the total number of telesets in operation in this country from increasing to at

least 50,000 by the end of 1946.

Basically, these receivers are of a similar quality as pre-war models, and are

sold at prices ranging from $180 for small-sized units to about $300 for full-sized

screens. The higher priced, four-in-one combination sets comprising sight and sound

with phonograph and automatic recording retail at approximately $700.

France, too, has made progress in television receiver manufacture in recent years,

and table models equipped with dual dials for vision/sound adjustment and synchronising/brightness

control are scheduled for release shortly to the public at popular prices.

Similarly, Russia, Switzerland, Italy, Holland and Belgium - countries which

have either resumed television production or else are contemplating its commencement

in the near future - are today making efforts to build up markets for telesets.

Since the popularity of television is governed to a large extent by the cost

of purchasing receivers, unit sales will be precluded from rising appreciably above

pre-war figures by the material impoverishment of Europe, as long as prices are

maintained at their present levels; a glance at the income structure of even Britain,

a country still enjoying the highest standard of living in Europe, shows that 85

per cent of her net national income is in the hands of families with incomes below

$2.000 per annum.

Accordingly, it can be taken for granted that the lower income groups of Europe

will not be able to command the use of television unless their purchasing power

is raised or prices reduced through large-scale production of low-priced sets.

The Current Market Outlook

Europe is today bulging with customers willing to buy radio and television receivers

at almost any price and no amount of stuff poured into this continent's markets

can possibly exhaust its absorption capacity without leaving a wide margin for additional

quantities.

Accountable for this state of affairs is, in the first place, the fact that in

spite of miracles of improvisations performed in the absence of proper tubes, accessories

and parts by radio engineers, technicians and manufacturers in some countries, few

receivers were made in Europe between the end of 1939 and mid-1945 apart from a

mere trickle of war-time civilian radios of the utility type in Britain and junked

sets and crystal detectors in France, Holland, Belgium and elsewhere.

The magnitude of the existing potential market can be best gauged, perhaps, if

it is realized that approximately one-third of Europe's 85 million odd radios in

use at the time of the outbreak of the war are today destroyed, damaged or otherwise

out of order and the number of sets of all types needed as replacements, as well

as to fill the demand for new receivers, is reliably put at least 50 million.

No matter how anxious manufacturers over here may be to restore the volume of

their production to pre-war levels or step up beyond it, this demand cannot be met

by the European radio industry single-handed for a long time to come; nor can it

be filled, of course, by unloading limited quantities of usable surplus radio equipment

from military stores.

Consequently, it can be anticipated that U.S.-made radios will figure prominently

in post-war European radio sales and millions of dollars' worth of sets, imported

from America, will find a ready market among would-be buyers, unable to obtain other

than inferior quality and second-hand models at fantastic prices.

However, any U.S. radio manufacturer who intends getting rich by pushing cheaply

produced radios overseas, irrespective of whether they are aesthetically acceptable

to Mr. Babbitt's opposite number across the Atlantic, will soon discover at his

cost that a stable export trade can only be built up when bearing in mind that a

sizable share of Europe's post-war radio market will be geographically occupied

as follows: -

1. Western Europe. Full-sized performance superhets and midget superhets combining

technically all the advantages of the normal superhet, including its superb acoustic

reproduction facilities, as the so-called second or auxiliary set in the bedroom

or kitchen.

2. Northern Europe. Economically-priced, workmanlike multi-band receivers of

medium and high-class performance.

3. Southern Europe. Low-priced, straight receivers, superhets and midgets of

effective range and satisfactory output.

4. Eastern Europe. Simple type receivers of single and double band range and

limited selectivity in which quality is subservient to price.

1Approximately half the world's .combined total radio production output

at the time without the U.S.S.R.

|