|

The

Civil

Air Patrol (CAP), being made up primarily of volunteer, unpaid airmen and officers,

has been serving the country since World War II, as highlighted in this 1957

Radio & TV News magazine article. Many members use (or at one time

used) their own aircraft and radio gear in the service of the country. Per the CAP

website, "In the late 1930s, more than 150,000 volunteers with a love for aviation

argued for an organization to put their planes and flying skills to use in defense

of their country. As a result, the Civil Air Patrol was born one week prior to the

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Thousands of volunteer members answered America's

call to national service and sacrifice by accepting and performing critical wartime

missions. Assigned to the War Department under the jurisdiction of the Army Air

Corps, the contributions of Civil Air Patrol, including logging more than 500,000

flying hours, sinking two enemy submarines, and saving hundreds of crash victims

during World War II, are well documented. After the war, a thankful nation understood

that Civil Air Patrol could continue providing valuable services to both local and

national agencies. On July 1, 1946, President Harry Truman signed Public Law 476

incorporating Civil Air Patrol as a benevolent, nonprofit organization. On

May 26, 1948, Congress passed Public Law 557 permanently establishing Civil Air

Patrol as the auxiliary of the new U.S. Air Force. Three primary mission areas

were set forth at that time: aerospace education, cadet programs, and emergency

services."

Operation Jupiter

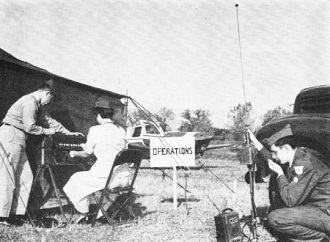

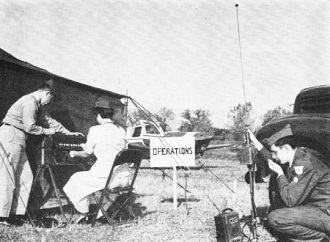

A CAP pilot uses his aircraft radio as a mobile control "control"

providing instructions to other CAP airplanes which are engaged in the air search

and rescue mission.

By Frank Burnham

Mobile radios in cars and planes, plus fixed stations at CAP headquarters, combine

in daring flood rescue operation.

Pelting rain continued to come down as it had for more than 72 hours. Three days

of downpour turned the brooks into creeks, the creeks into rivers, and the rivers

into seas of raging destruction in western Virginia, southern West Virginia, and

southeastern Kentucky. Rising water forced the Guyandot, Clinch, Kentucky, and Cumberland

rivers out of their banks. And the rain kept up.

In a 15,000-square-mile area dominated by rugged hills, narrow valleys, and scores

of soft coal mines the cry "flood" threw terror into the hearts of the mining folk.

For the next five days they lived with terror. Death and destruction reigned in

the shadow of the Clinch Mountains.

Almost immediately state and federal relief agencies swung into action. The American

Red Cross marshaled its forces. The Federal Civil Defense Administration ordered

its field office to give all possible support. Governor A. B. "Happy" Chandler of

Kentucky and Governor Cecil H. Underwood of West Virginia asked President Eisenhower

to declare the region an emergency area.

Even earlier, however, a relatively unknown and unrecognized group began emergency

operations - operations which later were to prove vital to the overall relief effort

in "Operation Jupiter" as the flood mission was to be called.

This group was made up of civilian volunteers wearing the familiar blue uniform

of the United States Air Force. Only the insignia was different. The volunteers

were members of the Civil Air Patrol, official USAF auxiliary, and their part in

"Operation Jupiter" was to be a big one.

Lt. Col. Huston H. Doyle, 43-year-old CAA chief airways operations specialist

who commands the Civil Air Patrol's Kentucky Wing in his spare time, prepared a

message to all CAP units in Kentucky. Especially to London and Hazard, in the path

of the flood waters, he signaled:

"Request your squadron provide all possible assistance ...."

The rolling tide of disaster unleashed by the heavy rains moved faster than expected.

As Doyle was preparing his message, Middleground One Six, communications station

of the Hazard Squadron, came on the air with a desperate plea for help.

CAP cadet ground rescue team boards Eighteenth Air Force "Vertol"

(H-21) helicopter to answer a distress call broadcast by a Civil Air Patrol radio

station during a recent flood disaster. This is a typical CAP function.

Lt. Bill Roll, 26-year-old Army veteran who wins the family bread as an LP gas

serviceman, was at the microphone. The building at the Hazard airport which housed

both the CAP headquarters and the State Police was already under water. Roll was

operating from his home on high ground and on power supplied by a small, gasoline

generator kept for emergencies. His message, which was picked up as far away as

Atlanta, Ga., said:

"Hazard business district completely wiped out. Four feet of water in Peoples'

Bank. Five million dollars damage. Several hundred people out of homes. Will be

several days before contact possible by any other means than CAP radio net."

The message was signed by Dewey Daniels, Kentucky state Republican chairman.

The Kentucky Wing immediately forwarded it to the office of Governor Chandler. Meanwhile

CAP communicators Capt. J. R. Patterson and Lt. Peggy Wade, who had picked up the

call in Atlanta, Ga., were also forwarding it to the Kentucky governor.

During the next four days Middleground One Six was the only contact with the

stricken community. When Army engineer companies from Fort Knox broke through 48

hours after the first desperate message they found Roll still on the job.

Meanwhile in Louisville Colonel Doyle was busy arranging for a high-priority

airlift of serum and vaccine to the flood area. CAP light planes, picking up the

life-preserving fluid at Lexington and Louisville, transported it to London where

a combined disaster operations headquarters had been set up. Here the precious vials

were put on helicopters for the last leg of the journey into the area where nature

had run wild.

The first two days of the emergency Colonel Doyle made his headquarters at the

London, Ky., airport where CAP Maj. Roscoe Magee and the London squadron had been

on duty since Lieutenant Roll's dramatic message went on the air. Through Lt. B.

L. White, the squadron chaplain and a ham operator (W4UVH), the London CAP communicators

maintained contact with Kentucky hams who also pitched in with an assist to their

troubled state.

Going on the air at 1930 CST on January 29, Middleground Eight, the London Squadron

headquarters station, stayed on the air continuously until 0245 CST February 2.

At times atmospherics prevented direct contact with Hazard and a relay was set up

with Blue Chip One Three, Tennessee Wing, and Red Star Five, Georgia Wing.

"Operation Jupiter" turned out to be one of the largest missions in the history

of the CAP's Kentucky Wing. At its peak several hundred CAP civilian volunteers

- each one taking time off from his job or business, mostly without pay - were manning

the 18 fixed and mobile radio stations, the relief teams, and the aircraft. They

weren't alone, however. In Virginia and West Virginia their counterparts were doing

their share to stem the tide of death and destruction.

At almost the same time Bill Roll was telling of the plight of Hazard, the first

word of immediate danger in Richlands, Va., was coming in from Senior Member Mack

Blankenship (Blue Flight Seven) of Bandy, Va., six miles from Richlands in the heart

of the soft coal fields. Relayed by other Blue Flight stations, it. was received

at Hampton by Capt. Mildred Hicks, attractive wife of CAP Maj. Douglas Hicks, Virginia

Wing director of Communications. Mildred, who admits to some "30-odd" years, is

an ardent CAP communicator and keeps Blue Flight Three-Virginia's alternate net

control station - on the air when her husband is working at his full-time civilian

job as an electronics engineer with the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics

at Langley Air Force Base.

A radio-equipped CAP jeep and a radio-equipped ambulance aircraft

work as a team evacuating simulated casualties from an atom-blasted house situated

less than a mile from "Ground Zero" following a recent atomic test at Yucca Flat.

Nevada.

The message which began "Operation Jupiter" for Virginia read:

"Richlands under water. Severe damage except in business district. Need blankets,

food, and shelter."

Lt. Col. Alfred Nowitsky, deputy wing commander for Virginia, immediately ordered

the entire statewide CAP organization on 24-hour alert.

In Richlands Maj. Grady Dalton, commander of the Richlands Squadron, who in private

life is the vice-president and cashier of the Richlands National Bank, already had

his unit at work aiding in the evacuation of citizens from flooded areas of the

town. Two of Dalton's mobile cars were on the air maintaining contact with CAP stations

outside the flooded region.

Another of the Richlands mobile cars, operated by Lt. Burkley Whited, was on

its way from the Whited home in nearby Swords Creek. It was some time, however,

before the 48-year-old carpenter reached Richlands. Whited got as far as Reven,

Va., when he found his way blocked by flood waters. Turning back he found the flood

had cut him off from behind. Some minutes later other CAP stations in the area heard

Whited report:

"I've got a mile and a half of road and no place to go."

A Cadet operates an SCR-511 "Pogo Stick" high-frequency transceiver,

relaying instruction to CAP aircraft engaged in disaster relief training mission.

Cadets at left operate a telephone switchboard tied into the local Civil Defense

agency.

He spent the night on a low ridge between two roaring torrents of water relaying

messages for other CAP stations that were maintaining the long vigil.

One of the first orders issued by Colonel Nowitsky was to the Tazewell Squadron

- the CAP unit closest to Richlands. Immediately three mobile radio cars operated

by Lt. Sam Evans (Green Flight One Two Three), Senior Member Aubrey McCracken, and

Lt. Carless Chaffin were dispatched to the aid of beleaguered CAP forces in Richlands.

Senior Member Walter Blankenship (Blue Flight Nine) was assigned to coordinate the

activities of the mobiles. During the periods he was to be off duty in his capacity

as a Virginia State Trooper another CAP communicator, Lt. Luther Mercer, was to

back Blankenship up.

None of the three mobiles was able to find a surface route open into the stricken

community. After several tries it was decided that Chaffin and McCracken would return

to their base of operations. Evans planned to continue his search for a way into

Richlands.

Over the radio Evans told Blankenship he would stock his outboard motor boat

with food and other supplies and would make another try. At home Mrs. Evans overheard

the conversation on their monitor receiver. By the time he arrived at the house

she had stripped the family pantry, loading every available item of food into the

boat along with blankets and warm clothes. Stopping only for a word of thanks, Evans

hitched the boat trailer to his mobile radio car and headed back toward the swollen

Clinch River.

He might have a chance, he reasoned, to get through overland if he tried the

many narrow, winding mountain roads in the area. Perhaps one of them would be open.

Heading down Baptist Valley, he found the bridge under water. Another road, another,

and still another was under water when he tried them. On his last try before taking

to the boat he found an open road. Reporting to Grady Dalton in Richlands, Evans

found it had taken him two hours to go 17 miles. He found also that the route he

used became impassable almost immediately after he used it. It was two days before

Chaffin, McCracken, and the Tazewell CAP land rescue teams got through to relieve

him and Dalton's weary men.

Meanwhile Sam Evans' relief after 48 hours of duty in Richlands was short lived.

Sam went home and dropped exhausted into bed. The next day he planned to return

to his job as a telephone inspector for the Pocahontas Fuel Co. At Bluefield, W.

Va., however, a chain reaction was beginning that was to demand more hard work and

personal sacrifice from Evans.

Most of that night CAP Capt. Jim Cheek, a 32-year-old Army veteran, and his wife,

Lt. Norma Jean Cheek, were busy moving emergency traffic. Their powerful Lowland

Four Four, alternate net control for the West Virginia Wing, blankets most of western

Virginia also with a strong signal. It proved a perfect relay station carrying traffic

also for the Kentucky and Tennessee wings. Cheek is a salesman for the Meyers Electronics

Go. of Bluefield and the next morning, leaving his wife to operate the station,

he began a business trip to nearby Grundy, Va., just across the state line.

At Oakwood, Va., Cheek was turned back by State Police who said that the route

was closed by flood waters.

Checking the situation, Cheek found that there were apparently no open routes

to Grundy. Returning to Bluefield, he went on the air with a report of the situation

to Blue Flight Three.

Civil Air Patrol communicators operate a high-frequency rig installed

in a surplus Air Force bus which has been converted into a combination mobile communications

station and a mobile operations headquarters for directing rescue work.

Colonel Nowitsky, Virginia Wing mission commander, immediately checked with all

state agencies in Richmond and found that there was no contact with Grundy nor had

there been contact for more than 12 hours. In a matter of minutes Sam Evans was

under orders to proceed toward Grundy keeping wing headquarters advised of his progress.

The State Director of Civil Defense asked Evans for an evaluation of 'the situation

if and when he got into the isolated community.

Lt. Chaffin (Green. Flight Four Five) was sent to Short Gap, Va., a high point

on the Buchanan County Line, to act as a relay. McCracken and Mercer were detailed

to assist Evans and another relief mission was on. It took the mobile radio cars

and the accompanying ground rescue team vehicles until 10 that night to get into

Grundy and then only with the aid of heavy equipment of the State Highway Department.

Evans reported immediately to the office of Mayor W. B. Raines and asked for an

assessment of the situation. He then sent this message - the first contact between

Grundy and the outside world in two days:

"One road now open one way. The one we used to come in on. Need clothing and

bedding for 100 families. Water not contaminated. Power back on. Water dropped from

30 feet above normal to 10 feet above normal. Ten thousand miners out of work. Need

Bailey bridges to mines. No loss of life. No other communications available."

When Cheek asked Evans if he could handle the situation in Grundy, the CAP citizen-turned-rescuer

replied:

"Just tell my wife I'll be here until Sunday and that I'm all right."

Meanwhile West Virginia was having its own troubles with the Guyandot River in

Logan County. CAP Maj. James Singleton is the coordinator for Civil Defense for

the West Virginia Wing. He also is Logan County CD director.

"We have had experience with disaster in Logan County for a long time," he explains,

"mine explosions, floods, complete disruptions of all types of communications caused

by forest fires, and snow and ice storms which cut us off from the world completely.

"Because of the continual rainfall for a 72-hour period we - the CAP- dispatched

a mobile radio car to the headwaters of the Guyandot. We checked rainfall and water

level in the tributaries also. This was Monday. From past experience we determined

that the river would begin approaching flood stage about 10:30 Tuesday morning.

The Logan Squadron immediately made plans to meet the emergency.

"Communicators were alerted and were warned to have their mobiles moved to high

ground out of danger from the water so that they would be usable if and when the

flood struck. Four fixed stations and 14 mobiles went on the air.

"We sent CAP mobile cars through the probable high-water areas warning citizens

to evacuate to high ground and assisting in evacuation wherever possible. Lt. Raymond

Chapman (Overland Two Six) alerted this area - Champanville. Man, W. Va., was alerted

via radio and CAP members there began warning the population."

Now the Red Cross, Civil Defense, State Police, and county law enforcement agencies

took over the actual disaster assistance work while CAP stood by to provide emergency

communication.

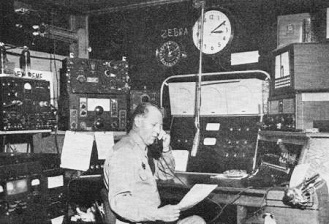

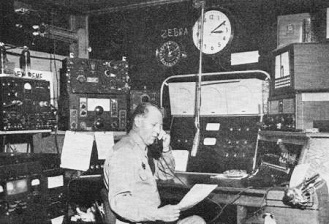

Typical of the more than 5000 fixed stations used by the CAP

is this installation being operated by CAP 2nd Lt. Kenneth Lofstedt, exec of the

CAP Squadron 90.

The work these civilian volunteers, like Singleton, performed in "Operation Jupiter"

isn't new. The precedent was established in the early months of World War II when

Nazi U-boats prowled our Atlantic and Gulf coasts sinking Allied shipping within

sight of the shore. For several months tiny, light planes piloted by CAP's unpaid

volunteers ranged out to sea spotting the submarines and reporting them by radio

to the Army and Navy bombers which at that time were few and far between.

For its wartime work the Civil Air Patrol was chartered by a grateful Congress

(Public Law 476, 79th Congress) to continue serving the people of the United States

- this time as a non-profit corporation dedicated to furthering the principles of

airpower and to using the airplane as an instrument of help and succor.

For the past six years these civilians have performed more than half of all the

search hours recorded by all participating agencies in aerial search and rescue

missions flown at the direction of the USAF.

In California's disastrous 1955 Christmas floods; in the wake of Hurricanes Hazel,

Diane, and Connie; in the Michigan tornados; and in "Operation Jupiter" CAP's emergency

communications capability was demonstrated.

At first communications in the Civil Air Patrol was a support function to the

aircrews just as it was in the Air Force. Today, however, emergency communications

is one of the CAP's assigned wartime missions and from all accounts it is a mission

in which CAP excels.

Operating on both high and very-high frequencies loaned by the Air Force (Public

Law 557, 80th Congress gave CAP auxiliary status), the Civil Air Patrol today has

nearly 14,000 stations in the 48 states, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth

of Puerto Rico, and Alaska and Hawaii.

High-frequency stations include 2605 fixed, 4351 mobile, and 254 airborne. The

v.h.f. facilities include 2510 fixed, 3926 mobile, and 438 airborne. Frequencies

used by CAP include 2374, 4467.5, 4585, and 4507.5 kc. At present only one v.h.f.

frequency - 148.14 mc. - is authorized. Only A3 emission (voice) is permitted and

all CAP transmitters must be crystal controlled. All CAP stations are FCC-licensed

and all CAP operators must have at least a restricted radiotelephone operator's

license.

At wing level (equal to the states and territories) 400 watts h.f. transmitter

power output is permitted, 150 watts at group level, and 75 watts at squadron level.

On v.h.f. 50 watts is permitted at all echelons. Mobile output is restricted to

the power output of the respective headquarters.

CAP communicators employ a conglomeration of equipment. Some of it is surplus

military equipment, mostly from World War II. The majority of it, however, is commercial

equipment purchased and maintained at the expense of the individual member. "Globe

Scout" and "Champion," Heath, Johnson "Viking," Gonset, and Aerotron are among the

nameplates to be found in CAP communications rooms. There you find BC-669, ARC-5,

ARC-4, BC-640, and SCR-522 equipment and perhaps even a few sets you never knew

existed. The important thing is that when the chips are down the Civil Air Patrol

always seems to turn in a whale of a job no matter what it has to work with or what

price must be paid.

The value of their work in "Operation Jupiter" can best be told in the words

of people who watched the CAP in action - people like Kentucky Governor A. B. "Happy"

Chandler. In a telegram to Maj. Gen. Walter R. Agee, USAF, CAP National Commander,

Governor Chandler said:

"Kentuckians are deeply grateful to the Civil Air Patrol for its assistance during

the recent disastrous flood in eastern Kentucky. CAP members and their radio communications

system performed nobly in helping protect lives and property. CAP radio at Hazard,

using emergency generators when the city's power system failed, sent out first calls

for help from the stricken community. Then Hazard radio working with CAP radio units

in London, Middlesboro, and Louisville, dispatched messages which brought in food,

clothing, and medicines. Throughout the flood crisis every Civil Air Patrol member

involved performed magnificently and they have certainly earned our undying gratitude

and esteem."

Posted January 7, 2022

(updated from original post on 11/19/2013)

|