|

Deadbeat customers have been

a problem since time immemorial. Said dirt bags ask you to perform a service and/or

provide a product and then either try to cheat you out of full payment or refuse

to pay at all. Back in the days when repairmen made in-home visits for radio and

television sets, evidently the problem could be really bad. Art Margoli wrote this

article for Radio & TV News magazine in 1957 describing methods he devised to

handle, and most importantly avoid, uncomfortable situations and stave off ugly

confrontations with customers. One such scheme was to have customers sign a "cognovit note," which is an extraordinary document by which a

debtor authorizes his or her creditor's attorney to enter a confession in court

that allows judgment against the debtor. Of course litigation would probably cost

more than the bill was worth and therefore would not likely be pursued, but the

cognovit note appeared intimidating with sufficient legalese to give pause to the

seasoned feckless homeowner. If you are in business for yourself and have similar

issues, maybe something here will work for you. Fortunately, I have only had a couple

incidences of companies not paying according to my very lenient terms.

Strategy for C.O.D Service

By Art Margolis

The chief customer types who try to defer

prompt payment and the techniques for discouraging them.

About a year ago the owner of a busy three man TV service organization, a

friend of the writer, was handed an ultimatum from his accountant. The accountant stated,

"You either raise your service charge or cut out your credit business."

Delinquent accounts had reached a new high of twelve-hundred dollars. The expense

of billing and special collection trips were eating deeply into the profits. Since

his service charge was considerable already, the TV expert decided to go on the

C.O.D. standard.

He quickly discovered there was one big problem with being strictly C.O.D. What

do you do with the customers who still ask for credit? A strict adherence to refusal

of credit was sending a percentage of his clientele elsewhere for TV service. He

was faced with the enigma of how to give some customers a form of credit yet remain

essentially on the C.O.D. standard.

Since the author's service outfit has always been C.O.D., the technician called

on the writer with his problem. A long conference ensued and the harried operator

was given a detailed description of a C.O.D. strategy that has been used successfully

for years.

Experience shows that there are four definite types of set owners who ask for

credit even though they know that business is transacted strictly on a C.O.D. basis.

The Careless Type

The writer ran into one of these only a couple of days ago. The TV was a three-way

combination Philco. The set owner was a well-to-do elderly lady. The home was on

the outer fringe of the service area. There was no audio, a weak picture, and slight

vertical foldover.

A new 12BH7 vertical-output amplifier fixed the vertical foldover. A new 12AV7

perked up the picture, but that's all tubes would do: the audio still remained silent.

The r.f. chassis was pulled out of the cabinet and the audio section inspected.

Visually a slightly charred resistor was spotted. It was the "B+" dropping resistor

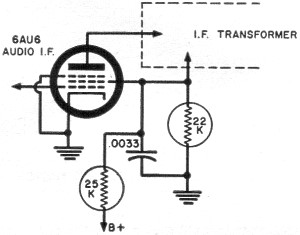

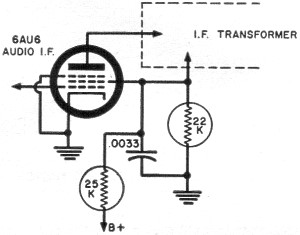

in series with the screen of the 6AU6 audio i.f. (see Fig. 1). The ohmmeter

read it as 6000 ohms instead of its called - for 25,000 ohms. It was replaced.

The chassis was hooked up and the TV turned on, still no audio. Evidently something

else had burned up the resistor. A screen-to-ground resistance reading was taken.

The meter read 4000 ohms. The schematic (Fig. 1) showed a 22,000-ohm resistor

to ground and, in parallel with the resistor, was the power supply through the new

25,000-ohm resistor. The meter should have read no less than 10,000 ohms under these

circumstances. The 22,000-ohm unit was disconnected. It was the culprit. It read

4000 ohms.

The "B+" dropping resistor had been electrocuted because the 22,000-ohm unit

had shorted down, thus dragging a lot of current through both units.

The r.f. chassis was replaced and the audio sounded off. However, the damper

was also replaced for arcing. The bill was unavoidably high. When the little old

lady received the bill she said helplessly, "All I have home is five dollars. Whatever

are we going to do?"

Fig. 1 - One defective component caused another in this circuit.

The writer carried out the strategy for the "careless" type. He collected the

five and marked on the receipt the balance due. Under that sum he printed in large

letters. "WILL MAIL IN 48 HOURS" and had her sign beneath it. He gave her the carbon.

Then he handed her a stamped, addressed envelope and smilingly instructed her simply

to put the cash, check, or money order in the envelope and drop it in the mailbox.

The click-click efficiency and tactful concern over the unpaid balance worked

as it usually does. A check arrived. the next morning. For these people who are

simply careless enough not to have enough money around to meet their daily requirements,

the collection message must be brought home strongly but not offensively. The readied

envelope eliminates the obstacle of the customer having to make one up, and the

signature imparts a strong sense of obligation and urgency. In the great majority

of cases, the money arrives in the mail quickly.

The Suspicious Type

A second type of individual who asks for credit under all circumstances are those

people with suspicious natures. They feel that if they can hold back payment for

a length of time they have a weapon by which they can force a TV technician to stand

behind his work. The suspicious types are hard nuts to collect from, but it can

be done. The technician has the job of instilling enough confidence in the customer

to enable him to waive his hard rule of holding back payment.

A perfect "suspicious" type lugged his receiver into the shop the other day.

He left his name, address, and telephone number and departed. After the set was

repaired, the customer was called and arrived promptly.

He tried to pick up the TV but was handed the bill first. He said, "I'll mail

the money in." When reminded of the shop's C.O.D. policy he blurted, "If the set

works okay for a while you'll get your money; don't worry."

The writer tactfully went all through the facts that the work is guaranteed,

that the company is bonded, and that even though the bill were paid the guarantee

would be just as good. The gent stood firm. Since the TV was still in the shop,

there was no problem - possession is "nine tenths!" However, insistence would have

meant irritation and the loss of good will. The writer went into the strategy for

suspicious customers.

"Sir," he said slowly, "You are going to mess up our bookkeeping by holding back

the money." He took off his wrist watch. "If you don't trust me sir, here is my

wrist watch. When you are satisfied with the repair you can bring it back."

The beefy fellow lost all his belligerency, paid the bill, shook hands amicably,

and left with his set. This wrist watch has been offered many times - it has never

been accepted yet.

The Professional Beat

Unfortunately there is a small percentage of people who believe that the word

"credit" is synonymous with "free gift." They feel that if any firm is fool enough

to give them an open account, that firm will just have to suffer the consequences.

A TV technician can spot these professional "beats"; they all tip their hand

with the same routine. They do not mention a word about payment until the technician

has fully completed his work. Then, after all the screws are back, the set is perking

nicely, and the tool box is closed tight, they say, "I don't have no money."

The writer's outfit has a strategy reserved for this set of circumstances. It

was used recently by one of the outside men. All of these outside men carry with

them copies of a certain type of contract - an impressive looking legal paper -

known as a "cognovit note." It is used only in extreme cases where it is obvious

that the intentions of the customer are not honest. A copy of this document is shown

in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 - Those who appeal for credit

with dishonorable intentions usually can be discouraged with the stringent legal

form shown here.

The cognovit note is an iron-clad note of indebtedness. It is a promise to pay a

certain sum by a certain time. If the money is not paid, the undersigned confesses

an automatic judgment in favor of the holder, waiving all legal rights. The undersigned

also agrees to pay all costs and interests that accumulate in satisfying the note;

If the note is signed and payment is not forthcoming on time, all that is necessary

is to turn the note over to a constable, justice of the peace, or a collection agency.

In this case the set owner, after reading what she had to sign, managed to get the

money together. They usually do.

Honest Embarrassment

The fourth type of credit-seeking customer is one who honestly doesn't have the

money to pay his bill. There is a method to extend these people a form of credit

and practically eliminate all risks.

The writer used it this week on a 16" Emerson repair. One of the field men pulled

it into the shop for lack of horizontal sweep. There was a bright, jagged stream

of light that extended top to bottom on the screen. A schematic was pulled and troubleshooting

started.

The horizontal circuits were examined first. They passed all resistance, voltage,

and waveform tests. The trouble seemed to be somewhere past the horizontal output

amplifier. The yoke and high voltage transformer were checked by tacking in new

replacements. The new replacements didn't change the trouble in the slightest. All

the components in the damper circuit were checked; every part was good. This one

was weird.

The boosted "B+" was investigated. Everything checked satisfactorily. The only

circuit that was left that could possibly cause this condition was the power supply.

The schematic was perused to find a clue. It revealed there was an isolated filament

winding in the low-voltage transformer for the damper. That is, it was supposed

to be isolated.

A resistance check showed there was an 800-ohm short from this winding to ground.

The transformer had to be replaced.

The bill was high. The set owner, after hearing the sad news said, "It's going

to take me a month to pay the bill." Then he asked, "Is there any way I can get

the set now?"

The set owner was asked if he had a checking account. He answered yes. The customer

was then instructed to make out a check. He was informed that the check would be

held a month before cashing it. All he had to do was cover the check by the time

the month had elapsed.

The TV was then delivered, a check was paid for it, even though the check lay

in a drawer for thirty days, and everybody concerned was happy.

It's been a year now since the owner of that three-man organization, mentioned

at the beginning of this story, has been on the C.O.D. standard. Actual results

show it has been a wise move. In comparison to the previous year's $1200 in delinquent

accounts, this year's record didn't reach fifty dollars, and these few lost dollars

can be directly traced to professional beats.

The volume of calls has increased. The owner attributes part of the increase

to the "no-credit" policy. First of all, he claims that he has gained customers

because he no longer loses his clientele by having to hound them for money. Also,

he no longer loses clientele because they are ashamed to call him when they owe

him money.

The fact that a TV service outfit is on the C.O.D. standard doesn't mean there

are no longer any forms of credit. An outfit must bend a little to cater to the

few inevitable requests. But each request will fall into one or overlap into a couple

of the four types noted. If a TV company is prepared with stamped envelopes, a bit

of dramatic salesmanship, official cognovit notes, or the holding check gimmick,

the credit requests can mostly be satisfied without a loss of customers.

Posted June 2, 2022

(updated from original post

on 12/23/2013)

|