|

November 1965 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

You probably won't find too many people stacking

television antennas these days, but many Hams still do it. Vertical stacking is

used primarily to increase overall gain without appreciably altering the azimuth

beam, while horizontal stacking forms a tighter azimuth beam without appreciably

affecting the overall gain. When it comes to optimizing antenna designs installations

for operations below about a gigahertz, Amateur Radio practitioners have pretty

much written the book on the subject - actually, they have written hundreds of books

on the subject. Antenna stacking is often used in areas where space and/or neighborhood

covenants restrict the size and placement of external structures, but as pointed

out in this article, it also may be the only solution for getting consistent performance

in the presence of widely varying signal path conditions. Note that the TV channel

/ frequency table does not include the UHF band. That is likely because UHF at the

time (1965) was not where the major broadcast stations transmitted, so not as many

people would have been concerned with them. It wasn't until the mid to late 1950's

in the U.S. that

UHF started becoming widely used. You probably won't find too many people stacking

television antennas these days, but many Hams still do it. Vertical stacking is

used primarily to increase overall gain without appreciably altering the azimuth

beam, while horizontal stacking forms a tighter azimuth beam without appreciably

affecting the overall gain. When it comes to optimizing antenna designs installations

for operations below about a gigahertz, Amateur Radio practitioners have pretty

much written the book on the subject - actually, they have written hundreds of books

on the subject. Antenna stacking is often used in areas where space and/or neighborhood

covenants restrict the size and placement of external structures, but as pointed

out in this article, it also may be the only solution for getting consistent performance

in the presence of widely varying signal path conditions. Note that the TV channel

/ frequency table does not include the UHF band. That is likely because UHF at the

time (1965) was not where the major broadcast stations transmitted, so not as many

people would have been concerned with them. It wasn't until the mid to late 1950's

in the U.S. that

UHF started becoming widely used.

Update: See

Mr. Dave Jones' stacked TV antenna project that used information

in this article for phasing dimensions.

How to Stack TV Antennas to Increase Signal Strength and

to Reduce Ghosts

By Lon Cantor, Jerrold Electronics Corp.

If one antenna is good, why aren't two better?

They are. Two properly stacked antennas will bring in about one-and-a-half times

more signal voltage than a single antenna; a stack of four can almost double the

signal voltage. Of course you can't just keep doubling the antennas indefinitely.

Beyond eight, there is no appreciable increase in signal pickup. If one antenna is good, why aren't two better?

They are. Two properly stacked antennas will bring in about one-and-a-half times

more signal voltage than a single antenna; a stack of four can almost double the

signal voltage. Of course you can't just keep doubling the antennas indefinitely.

Beyond eight, there is no appreciable increase in signal pickup.

However, increasing signal strength isn't the only reason for stacking antennas.

In fact, it isn't even the best reason. If you need more signal pickup, you may

be better off buying a more expensive, higher gain antenna than stacking two antennas.

And, if even the best antenna you can find doesn't do the job, you should probably

add a good mast-mounted preamplifier.

When should you stack antennas? When you are faced with certain reception problems

that can't be solved in any other way. There are two ways to stack antennas: vertically

and horizontally.

Vertical Stacking. There are three reasons for stacking antennas

vertically:

(1) To reduce signal fading from distant TV stations;

(2) To reduce airplane flutter;

(3) To increase signal pickup.

Because TV signals are so high in frequency, they are limited primarily to line-of-sight

distances. However, by various means, they do manage to get to "blind" areas and

regions a short distance over the horizon. While lower frequency radio waves do

follow the curvature of the earth and TV signals don't bend very well, a small portion

of the TV signal does bend around obstructions to get to the antenna. This can take

the form of a knife-edge type of diffraction as from the roof-edge of a building,

or a gentler slope as from the top of a hill.

Television signals also reach the fringe antenna by reflection-bouncing off of

atmospheric interfaces, and refraction-bending caused by atmospheric layers with

different densities.

Let's suppose you're putting up a fringe antenna. You won't get the most signal

just by mounting the antenna as high as possible. Instead, you must carefully probe

for the height that gives you the best possible TV pictures. Because of the methods

of signal propagation, this height is quite critical. It is the height at which

most of the diffracted, reflected, and refracted signals that are present arrive

in phase. At heights at which these various signals arrive out of phase, they actually

subtract from each other.

The trouble is that the signals that reach the antenna by atmospheric reflection

and refraction are not stable. They change as the atmosphere shifts. This is the

main reason for signal fading in fringe areas.

The solution to this problem is the vertical stack. You put the two antennas

at different heights. Thus, when one antenna is receiving out-of-phase signals,

the other is receiving in-phase signals. If you combine these two antennas properly,

you wind up with an average signal that doesn't vary much. This is a form of diversity

reception.

Fig. 1. Hybrid splitter allows signals from each antenna

to add to each other, and minimizes loss when one antenna acts as a load on the

other. Leads to transformers and splitter should be equal.

Fig. 2. Select wavelength of lowest channel to adjust space

between stacked antennas to prevent mutual interference. Two-thirds wavelength is

minimum.

When the antennas are not delivering the same signal, the out-of-phase antenna

acts as a load to the in-phase antenna. Instead of getting additional signal, you

actually get less than the in-phase antenna alone can deliver, unless you effectively

isolate one antenna from the other.

Commercially available stacking bars won't do the job. Stacking bars are fine

when both antennas are delivering approximately the same signal. Obviously, this

is seldom the case in a fringe installation.

Figure 1 shows how antennas should be vertically stacked to minimize signal fading.

There are five important things to do to make a good vertical stack.

(1) Use identical antennas.

(2) If you use coaxial cable, such as RG-59/U, you should also use a weather-proof

300-ohm to 75-ohm matching transformer mounted as close as possible to each antenna.

(3) Use a hybrid type splitter. This type of unit is like a one-way valve. The

output contains the sum of the two inputs, with virtually no loss. Yet the two inputs

are isolated from each other. Even if the signal on one antenna goes down to zero,

it cannot subtract more than about 10% of the signal from the other antenna.

(4) Space the antennas at least two-thirds of a wavelength away from each other

on the mast. A full wavelength is preferred, but this is not always possible. In

calculating this distance, use the wavelength of the lowest channel in your area.

Figure 2 shows the wavelengths of all the VHF channels.

(5) Make the harness symmetrical. The lead run between each antenna and its matching

transformer must be identical. Similarly, you must use equal lengths of cable between

each matching transformer and the hybrid splitter.

Horizontal Stacking. It is foolish to use a horizontal stack

simply to increase signal pickup. It is easier, cheaper, and just as effective to

use a vertical stack for this purpose. Horizontal stacks, however, may be the only

possible way to do the following things:

(1) To reject ghosts;

(2) To minimize co-channel interference;

(3) To minimize adjacent-channel interference;

(4) To reduce man-made interference.

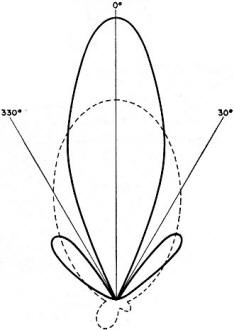

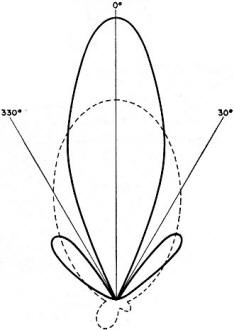

Figure 3 shows the reception pattern of one log-periodic antenna, compared with

that of two of them horizontally stacked. Notice that stacking not only increased

gain, but changed the pattern considerably. The stacked pattern shows two side lobes,

although there are others, with nulls in between. These nulls are important. You

can use them to get rid of unwanted signals.

The pattern shown in Fig. 3 is for one particular horizontal stacking situation:

when the antennas are stacked precisely one wavelength apart (center to center).

Notice that under these conditions nulls are produced at 30° to the right and

left of 0°.

Fig. 3. Angle of null points can be changed by adjusting

the spacing between horizontally stacked antennas (solid line) to drop out interference.

Dotted line is response curve of single antenna.

Now, suppose you had a tall tower reflecting a ghost signal from an angle 30°

away from the transmitted signal. You would simply aim the two antennas at the transmitter,

the ghost would conveniently fall into the null, and you'd never see it on the TV

screen. It is seldom, however, that you can count on unwanted signals coming in

from precisely one of those angles. Therefore, you have to find a method of varying

the angles of the nulls.

Fortunately, this is quite simple. All you have to do is vary the horizontal

spacing between the antennas. And you don't need any complicated formulas or measurements,

either. The trial and error method works best.

Before you start shifting the antennas, you should construct a symmetrical harness

- same type leads, lengths, and matching transformers - between the hybrid splitter

and the antennas.

Point both antennas directly at the transmitter. Keeping them parallel, slowly

move one antenna closer to, or away from, the other. While you are doing this, you

need someone to watch the TV set for a sudden, sharp reduction in the unwanted signal.

Secure the antenna in this position. The unwanted signal may still be noticeable

in spite of the sharp reduction. But, you're not through yet.

Remember that the unwanted signal must appear as equal and opposite polarity

voltages to cancel out. By finding the correct horizontal spacing, you've made sure

that the unwanted signal arrives at the two antennas 180° out-of-phase. Now,

you must make sure the signals are equal. To do this, simply move one antenna up

and down on the mast while someone again watches the screen. Secure the antenna

at the point where the unwanted signal is weakest.

Horizontal stacking is used to clean up master TV antenna systems, and it works

just as well in home TV installations - especially color installations.

Posted April 3, 2024

(updated from original post

on 4/17/2016)

|