January 1961 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

This 1961 Popular

Science magazine article demonstrates that lightning protection

fundamentals remain unchanged: ungrounded antennas attract strikes rather than

prevent them. Modern understanding confirms that lightning seeks the path of

least resistance to ground, and protection still relies on providing that path

through low-impedance conductors. While 1961 specifications called for #8 copper

cables and deep ground rods, today's National Fire Protection Association (NFPA

780) standards maintain similar principles with updated materials and

installation practices. Modern systems still use air terminals, down conductors,

and grounding networks, though we now incorporate enhanced bonding techniques

and surge protection devices for electronics. The physics of "hot" versus "cold"

lightning and streamer formation described in 1961 align with current models,

confirming that proper grounding remains the absolute requirement for diverting

lightning's destructive energy safely into the earth.

Lightning - Nature's mysterious display of pyrotechnics

By Art Zuckerman By Art Zuckerman

After putting the finishing touches on a guy wire, Bill Robbins climbed down

from the roof. Once back on the ground, he looked proudly at the several, antennas

rising up from the roof of his new suburban home. With all that stuff up there,

Bill thought, this is one house that doesn't have to worry about lightning!

But a week later the granddaddy of all thunderstorms struck. One colossal bolt

made a direct hit on Bill's house, starting a roaring fire it the wood-frame structure,

and at the same time knocking out the phone. A grimy Bill watched dazedly as his

home went up in flames. And he dumbfoundedly asked, "How could it happen? Those

antennas...

If anything, those antennas had probably guaranteed that the house would take

a damaging lightning strike. Their presence on a building that was already the tallest

thing for miles around provided a natural pathway for lightning. And the fact that

the antennas weren't tied in with a good lightning protection system meant that

the lightning, once it struck, had nowhere to go but into the radio and TV gear

and into the non-conducting structure of the house.

Actually, had the antennas been connected to a protection system - or at least

been properly grounded - they could have made a very effective contribution to the

safety of the house.

What Is Lightning?

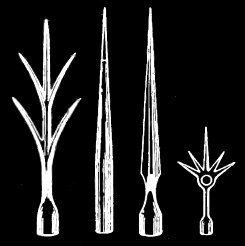

Air terminals, commonly called "lightning rods,"

are an important part of a protection system. Properly installed, they are the highest

points on protected structures, wired to dump thousands of amperes of static electricity

harmlessly into the ground.

Just how lightning is generated we can't say for sure. But we know that it's

the world's most colossal spark, created by the discharge of stupendous amounts

of static electricity. It can carry a punch of hundreds of millions of volts, a

current of 1000 to 100,000 amperes or more.

We also know that there are two basic types of lightning. The so-called "cold"

variety has extremely high voltages, combined with relatively low amperages. It

hits and disappears within 1/10,000th of a second. It doesn't often start fires,

but the enormous pressure of its passage can literally explode whatever it hits.

"Hot" lightning, on the other hand, has extremely high amperage but relatively low

voltage. With a core path temperature as high as several thousand degrees, this

is the type that almost invariably starts fires.

Like all electric sparks, lightning results when the potential between negative

and positive charges becomes great enough to cause arcing. In some cases, the arcing

goes through a barrier of air between the negative charge in a storm cloud and the

positive charge of earth. While we don't know the exact mechanics by which this

potential is built up, we do know the rough sequence of events.

A thunderstorm is generated when a layer of cool air overruns a mass of low-lying,

moist, warm air. The warm air tends to rise through the cool air, causing its moisture

to condense into water droplets. This movement of air current against air current

- and possibly of droplet against droplet - generates staggeringly large quantities

of static electricity.

For some reason, negative charges tend to collect in the lower layers of a storm

cloud and positive charges in the upper layers. One theory is that raindrops falling

through the cloud pick up negative ions and deposit them as they pass through the

lower layers. In any event, the massive negative potential of the lower cloud layers

induces a matching positive potential in the earth below. As our highly-charged

thundercloud scuds across the skies, the corresponding positive charge on the earth

follows along below, chasing after the airborne source of negative potential. The

attraction between the opposing charge causes corona-like negative streamers, or

stroke leaders, to descend from the cloud. As they approach the ground, these negative

streamers become the focal point for the earth's positive charge.

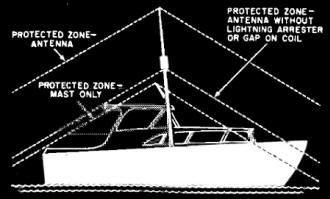

Lightning Protection Afloat

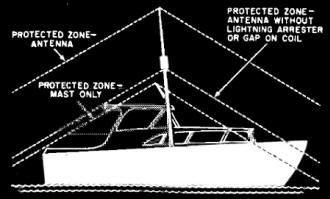

If you're a boating enthusiast, you'll be concerned with lightning protection

afloat. The marine radio antenna of a small boat, if it's a metal rod type, can

generally be depended on to do a bang-up protection job - provided that it's linked

to a metal hull or connected to a ground plate in a wooden hull by No. 8 copper

cable. If a wooden hull has no ground plate in contact with water, the cable can

be run over the side of the boat, into the water.

A word of caution: the above does not apply to a non-conducting antenna mast

with a spirally-wrapped conductor. But any mast can give protection if you put an

air terminal on top and link it with No. 8 copper wire conductor down to ground.

Any elevation or structure that will tend to shorten the gap between stroke leader

and ground is climbed by this positive charge. Reaching the top, it sends positive

streamers up from the elevation. The take-off point for these positive streamers

can be anything - an antenna, a flagpole, a silo, a house, or - if he is out all

by himself in open country - a man.

When negative and positive streamers meet, a tremendous current flow occurs at

the meeting place, and a huge return stroke races back up the path created by the

descending streamer. At the same time, an immense quantity of raw electrical power

is released into the earth. Whether damage will result depends on what physical

objects this power must pass through to reach the earth proper.

Obviously, lightning going through such non-conductors as wood or brick meets

with tremendous electrical resistance. But the massive electrical energy contained

in the lightning will not be denied; it smashes through this resistance. In the

process it generates enough heat to set fire to - or perhaps even melt - the structure

it hits.

Protection System

If the lightning hits a good electrical conductor, however, it takes this path

of least resistance, and its energy is carried harmlessly into the ground. In essence,

a lightning protection system is nothing more than a good conductor, designed to

provide the most likely target for lightning and offer a safe pathway to ground

for the lightning when it does strike.

Since objects which shorten the gap between the descending negative stroke leaders

and the earth's positive potential are the most likely lightning targets, they form

the ideal basis for a protection system. In fact, the obvious thing to do is to

make part of that system the highest point on the house.

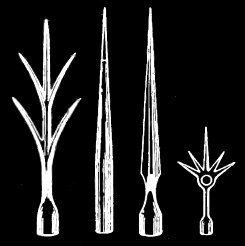

This highest point is familiarly known as the lightning rod. The modern version

of Benjamin Franklin's invention is a far cry from the large, often ornate creations

of earlier days. It even goes by a different name - the air terminal. Today's air

terminal is pencil-thin and pointed, deliberately designed to be as unobtrusive

as possible.

An air terminal by itself is a pretty useless item. In fact, as the initial point

on an electrical conduction system, it is a hazard, an open invitation for lightning

to pay a visit. The vital part of the system is a network of cables terminating

in a ground rod, buried deep in moist earth.

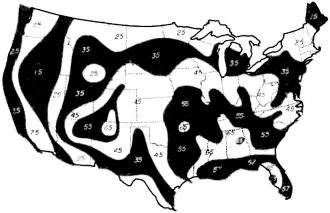

How About You?

Is it really necessary to have a full protection system? That depends primarily

on where you live. If your neighborhood is heavily built up and there are a lot

of tall objects in your immediate vicinity, danger is greatly reduced. But if you're

out in the relatively wide-open suburban or rural spaces - in an area that gets

a lot of storms - then it's a good idea to make the investment.

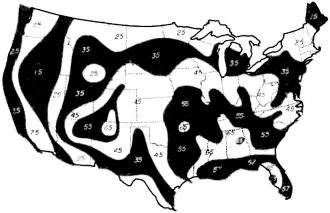

Number of thunderstorms per year varies with locale. Gulf coast of Florida tops

rest of nation with 85-95.

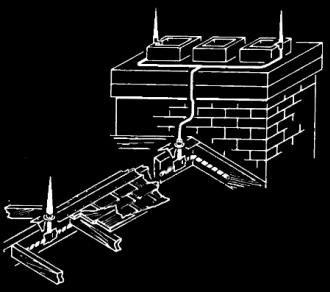

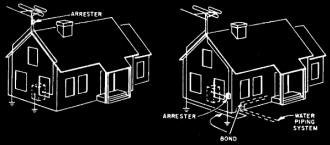

Any antenna can serve as an air terminal in a protection system.

The antenna mast should be grounded directly if a high-impedance lead-in is used;

lightning arrester should be mounted at same level as radio equipment as shown in

drawing above. Additional air terminals should be installed as shown below if antenna is not centrally located.

As a rule of thumb, for every thunderstorm that occurs within a square mile of

your home, you can figure on one or two lightning strokes hitting within said square

mile. If this adds up to, say, 50 storms a year, you have to reconcile yourself

to accepting 50 to 100 strokes annually within half a mile of your house.

Though lightning invariably strikes the tallest object handy, it is a temperamental

phenomenon and has been known to hit a small house sitting smack between two tall

buildings. This is so much the exception, though, that there isn't much point in

worrying about it. Actually, if you're near a tall, grounded metal structure, you

will benefit from the umbrella of protection it provides. A 100-foot grounded steel

tower, for example, should give complete protection to everything within a 50- to

100-foot radius. If your house is no farther away than twice the height of a grounded,

conducting structure, you should be fairly secure.

A good, properly-engineered protection system costs between $300 and $400 to

install, and there are good reasons for this seemingly high price tag. Let's examine

a properly set-up system in detail.

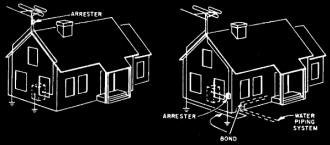

Air to Ground

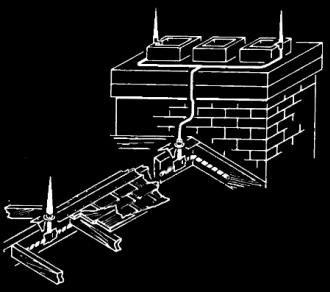

The air terminals at the top are usually made of copper for maximum conductivity,

and it generally takes several of them to do the job. They are installed at intervals

along every single high point of the house, such as gables, roof peaks, and chimneys.

In fact, a chimney whose diagonal measures more than four feet requires two air

terminals. On ridges, air terminals should be spaced no more than 20 feet apart.

The conductor cables are usually heavy affairs of copper - they weigh 187 1/2

pounds per 1000 feet, are made up of 17-gauge strands, and interconnect the air

terminals. Each air terminal must also have at least two down conductors, so that

it will have no difficulty dissipating a heavy lightning charge; generally, the

more down-running conductor cables, the better, since a multiple group of parallel

paths greatly reduces electrical resistance. All conductor cables must be free of

sharp bends that can encourage dangerous arcing; bends can have no less than an

8" radius and any turn must not exceed 90°.

Down conductors end in ground rods sunk deep into moist earth. These ground rods

must be either solid copper or copper clad, at least a half inch in diameter, and

10 feet long. A minimum of two ground rods are necessary, and they should be at

opposite ends of the house. In addition, every metallic object in and on the house

- radio -TV antenna masts, metal sidings, or eaves, plumbing and heating pipes,

ventilating systems - must be bonded together in the protection system and grounded.

This prevents side flashes, and it also guards against charges being induced in

these objects by a lightning strike, or even a direct entry by lightning.

Price Factors

Except for the ground rod, aluminum can be used in lightning protection systems

in place of copper. Aluminum is cheaper, but because it is less conductive, parts

made of this metal must necessarily be heavier and larger than similar copper parts

- making it harder to conceal the elements of an aluminum system. In any event,

clamps, connectors, and fasteners must be of the same material as the conductor

cables.

If you like, you can buy a kit and make your own installation. A copper kit for

a roof ridge running 60 to 80 feet costs between $100 and $200. An aluminum kit,

generally used only for metal roofs, is available for less than $100.

You'll want to consider the insurance angle. A lightning protection system with

a Master Label from Underwriters' Laboratories can earn you a lower fire insurance

rate. The only way to get such a Master Label is to have the system installed by

a UL approved contractor. In the long run, this may prove the more economical approach,

particularly when you realize that the standard guarantee runs 50 years and covers

free replacement of defective parts.

Antenna Protection

Although you may not feel a full investment in a complete lightning protection

system is justified in your particular case, you might find it worthwhile to protect

your antennas. As a matter of fact, if your antenna mast is spotted in the center

of your roof and there are less than 20 feet of roofing running out on either side,

an antenna can be rigged so that the entire house is adequately protected.

The rules are pretty much the same as with a regular protection system. A good

copper cable should be connected to the mast with an appropriate cable clamp. The

cable is then run along the roof ridge in either direction. If you have more than

one antenna mast, of course, they should be tied into the roof-spanning conductor.

The down-conductor and ground-rod setup is just the same as with a full-scale, standard

protection system.

Antennas call for additional protection - a lightning arrester which serves to

prevent lightning from entering the house via the antenna lead-in. Special lightning

arresters are also designed to protect power and telephone lead-in lines.

Actually, the term "arrester" is a misnomer, since the real function of this

device is to shunt lightning, or lightning-induced current, to ground. It makes

physical contact with the wires in your lead-in cable and is in turn connected directly

to a ground rod. An arrester can be attached to an antenna mast proper, but for

real protection one should be installed at the point where the lead-in begins. It

should be at least as close to ground as is the equipment connected to the lead-in

wire.

If your lead-in wire is a shielded cable, merely grounding the shield will serve

the same purpose as a lightning arrester. In fact, some authorities recommend running

shielded lead-in cable right into the ground before running it into the house.

Just what kind of protection system will best suit your needs is ultimately your

decision to make. But of this much you can be certain. With a system that is properly

installed and carefully engineered, the charge you get out of the next thunderstorm

will go safely to ground. And ground is precisely where it wanted to go in the first

place.

Lightning Protection Articles on RF Cafe

|

By Art Zuckerman

By Art Zuckerman