|

July 1948 Radio News

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early

electronics. See articles from

Radio & Television News, published 1919-1959. All copyrights hereby

acknowledged.

|

Benjamin Franklin is famous for his kite-flying experiment whereby he "discovered"

not electricity (as many people believe), but that lightning is a form of electricity

(most people thought it was a jet of gas). A lesser known fact about Mr. Franklin

is that he invented the lightning rod after realizing the electrical nature of lightning.

His understanding of electric fields facilitated an implementation whereby hefty

iron cabling interconnected a tall, pointed rod installed at the tallest point on

a building and a spike driven into the ground. Lightning typically strikes the object

that is the shortest distance (in terms of electrical field strength) from it because

the discharge can begin at the lowest voltage. The presence of the grounded lightning

rod above the highest point on a structure effectively brings that point all the

way down to ground level, rendering it no longer as electrically tall, thereby reducing

its likelihood of being struck by lightning. Contrary to common belief, the purpose

of a lightning rod is NOT to attract lightning and provide a discharge

path for the bolt. Benjamin (he insists I call him "Ben") was a hero in Philadelphia

where his invention almost totally stopped the rash of fires that occurred all around

the city whenever a major lightning storm occurred. Word quickly spread and soon

thereafter cities all over the world were being spared similar catastrophes after

installing their own lightning rods. Chalk another one up for American ingenuity

(which might be politically incorrect to point out these days).

Mac's Radio Service Shop: A Little Lightning

By John T. Frye By John T. Frye

The static crashes in the receivers Mac and his red-headed assistant, Barney,

were working on had been growing steadily louder and closer together; and when there

came a sudden sharp peal of thunder, Mac laid aside his test prods.

"Let's take a break, Red," he suggested as he started closing the switches that

grounded the AM antenna, the FM dipole, and the TV three-element beam; "that is,

if you think you can tear yourself away from your work."

"W-e-l-l-l, boss, if you insist-" Red said with a very phoney-sounding reluctance.

Mac tripped the circuit-breaker that opened both power leads going to the receiver

outlets and the test equipment and settled himself comfortably on the end of the

bench. Just then there was a brilliant flash of light accompanied by the vicious

"sn-a-a-a-p!" of a near stroke of lightning, and Miss Perkins, the office force

of Mac's Radio Service Shop, sailed through the door of the service department with

rather unlady-like haste.

"I-I just happened to think you boys might like some of these chocolates I picked

up during lunch hour," she said holding out the open box in hands that were noticeably

shaking.

Barney hopped off the stool on which he had been sitting and offered it to her

with a sweeping bow.

"You feed us candy, and we will protect you from the thunder," he promised as

he stretched his lanky frame on the floor and began to open and close his mouth

suggestively like a three-day-old robin.

"I don't think we need expect any customers for a few minutes," Miss Perkins

said as she looked through the door at the rain slashing down across the plate glass

windows of the shop; "and as for you, Mr. Smarty," she explained as she seated herself

primly on the stool and dropped a chocolate into Barney's gaping jaws, "I am not

afraid of lightning; I just don't like it."

"Anyway, you had better save your strength for answering the 'phone when this

is over," Mac told her as he helped himself liberally to the candy.

"How's that?" Barney asked,

"The lightning," Miss Perkins explained. "It always knocks out several sets.

"How, Mac?" Barney inquired. Before answering, Mac lazily sketched with his left

hand - it was the one with no candy in it - the diagram of Fig. 3 on the little

wall blackboard at the end of the bench.

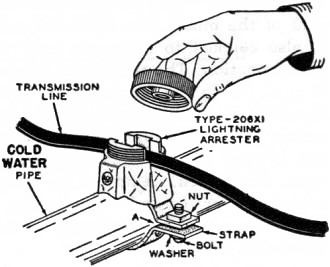

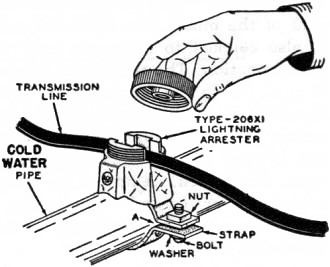

Fig. 1 - General Electric lightning arrester for use with

FM antennas.

"There you have the two circuits by which lightning can get into a radio - excepting,

of course, the remote possibility of a direct stroke, which is a fate that I wouldn't

even wish on a three-tube midget. You will recognize 'A' as the antenna circuit;

'B,' the 110 volt input circuit."

"Let's talk about 'A' first. If lightning strikes near the antenna, it induces

a voltage in the antenna wire which flows down through the lead-in, the antenna

coil, the chassis, and the ground lead to the earth. If the current is high enough,

it will burn out the antenna coil; if the voltage is sufficient, it will jump to

other parts of the receiver and may damage them."

"How much voltage and current does a stroke of lightning have?" Barney wanted

to know.

"That varies, of course, with different strokes. It is estimated, though, that

the voltage is around 100,000 volts per foot. That means that if the discharge leaps

from a mile-high cloud to the earth, the voltage is equal to 5280 times 100,000,

or more than five hundred million volts. The current varies from a few thousand

amperes to a few hundred thousand amperes."

Barney whistled. "If lightning strikes the antenna, then, about all you can do

is pick up the pieces - if there are any pieces."

Mac nodded agreement. "Yes, the things to protect against are static charges

and induced voltages. Even these are pretty hefty. It has been figured that the

voltage induced in a clothesline six and a half feet off the ground by a stroke

of lightning three miles away is often around 30,000 volts, and this voltage would

be increased by 4600 volts for every foot you raised the line. In an antenna with

considerable capacity, this induced current can become high enough to do great damage."

"What is the best protection against these induced voltages?"

"Grounding switches would probably be best if they were always closed during

electrical storms, but people either forget or are not around when the storm comes

up; so lightning arresters are the best bet. You have probably noticed that I keep

the shop key in that slot so I cannot get it out until the antenna grounding switches

are all closed. I forget, too!"

Barney waited until a window-rattling growl of thunder had subsided before asking,

"How are lightning arresters made?"

"There are dozens of different types. Resistor, horn gap, carbon pile, electrolytic,

coated pellet, oxide disc, neon gas - these are a few; but the important thing is

what they do. A lightning arrester is simply a device that has a high resistance

to the passage of current until a certain critical voltage is reached, at which

time it develops a low resistance that allows the high voltage to go to ground.

After this is done, it returns to its former condition. It is placed between the

lead-in and the ground, usually just where the lead-in enters the house."

"Most sets have built-in antennas now, though, don't they?" Miss Perkins asked.

"Outside of FM and TV sets, yes," Mac said. "But since these came along, people

are once again trying to get their antennas as high and as in the clear as possible

- right where the lightning likes to have them."

"I'd think a lightning arrester would upset the balance of a twin-lead lead-in,"

Barney offered.

Fig. 2 - RCA lightning arrester for use with FM and television

antennas.

Fig. 3 - If antenna terminal is connected to an external

ground, lightning surge may break down C1, thus shorting line through

the primary of the antenna coil.

"Ordinary ones would, but the engineers are bringing out new ones that don't."

Mac opened a drawer and tossed a couple of objects to Barney. "That long arrester

is made by G.E. and the round one is RCA. Both are made to clamp on a water-pipe,

and both are especially designed for use with twin-lead lead-ins from FM and TV

antennas. Some antennas of the folded dipole type are arranged so that grounding

the supporting mast also grounds the antenna itself at a voltage node and so affords

lightning protection without impairing the efficiency of the antenna."

"How about the damage done by lightning coming in over the line?"

"That is much more common in my experience than antenna damage," Mac said. "What

happens is that high voltages are induced into the power lines, sometimes at a point

some distance from the receiver, and it is piped right into the set by way of the

line cord. Once inside, it may raise all kinds of hob, such as arcing the line switch,

blowing condensers, burning out tubes, breaking down the insulation of the power

transformer - and I once saw where it had welded the tuning condenser plates into

a solid mass."

"Does it usually do all that?" Barney asked in awe.

"Fortunately, no. The most common damages are the blowing of line-filter condensers,

ruining of line switches and associated tone or volume controls, and burning out

of antenna coils."

"Wup! Wait a minute there!" Barney exclaimed. "How is lightning that comes in

over the power line going to hurt the antenna coil?"

Mac grinned approvingly at the boy's alertness and pointed at the diagram on

the blackboard. "Remembering that half the sets in town have the antenna posts attached

to the ground because the owners are too lazy to put up antennas, suppose a voltage

surge comes in on the ungrounded light wire and breaks through the insulation of

C1 to the chassis and proceeds through the chassis and the antenna coil

to the ground. The surge does not have to do all the work. All it has to do is break

down the insulation of C1, and then the line current will follow this

path and burn the fine wire of the antenna coil primary to a crisp."

"Tell him about the sets that turn themselves on," suggested Miss Perkins, who

was taking more interest in the conversation now that the thunder had subsided to

a distant growling.

"Well," Mac said, "suppose the surge does not puncture C1 but does

cause the insulation of C2 to break down. Then the line current can flow

right through the transformer primary, C2, the chassis, the ground lead,

and the ground back to the grounded side of the pole transformer, effectively bypassing

the receiver switch. People get pretty excited when their sets turn themselves on

during a thunderstorm and they cannot turn them off.

"What is the best protection against these line surges?"

"The best protection is for the customer to pull the plug out of the wall socket

during thunderstorms, and I warn all my customers to do that. One thing I have found

helpful is to put in d.p.s.t. switches in place of the usual s.p.s.t. type used

in receivers. By breaking both sides of the line, you increase the arc path, and

you remove the vulnerable line-filter condensers from the line except when the set

is turned on."

He was cut short by the shrilling of the telephone, and Miss Perkins ran to answer

it.

"Mac's Radio Service Shop; good afternoon!"

"You say the receiver started playing without anyone's touching it, and now you

can't turn it off? Well just pull the plug out of the wall socket and leave it out.

Do not try to plug it back in or you may blow a fuse. We will pick it up in a few

minutes."

Barney looked first at Mac's teasing grin and then at Miss Perkin's satisfied

smile.

"How smug can two people look?" he asked in mock disgust.

Lightning Protection Articles on RF Cafe

Mac's Radio Service Shop Episodes on RF Cafe

This series of instructive

technodrama™

stories was the brainchild of none other than John T. Frye, creator of the

Carl and Jerry series that ran in

Popular Electronics for many years. "Mac's Radio Service Shop" began life

in April 1948 in Radio News

magazine (which later became Radio & Television News, then

Electronics

World), and changed its name to simply "Mac's Service Shop" until the final

episode was published in a 1977

Popular Electronics magazine. "Mac" is electronics repair shop owner Mac

McGregor, and Barney Jameson his his eager, if not somewhat naive, technician assistant.

"Lessons" are taught in story format with dialogs between Mac and Barney. There

are 131 stories as of January 2026.

|

By John T. Frye

By John T. Frye