|

December 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Parts 1 and 2 of this

series covered the theory of nuclear physics and laboratory investigation devices.

This final installation talks about commercially available test instruments for

detecting and measuring nuclear radiation levels. My introduction to Geiger counters

was in the old The Adventures

of Superman television show (the originals with George Reeves) where they

were used by villains to verify that their stash of

Kryptonite

would be sufficient to disable our superhero. I could not find anywhere whether

Kryptonite's emission type is alpha particles (helium nucleus; i.e., 2 protons and

2 neutrons), beta particles (electron), gamma rays (electromagnetic waves), or some

other form. Multiple designs of detectors are used based on radiation type and strength

to be measured.

Side note: Did you know there are various

colors of Kryptonite, all with unique effects on former dwellers

of the planet Krypton?

Parts

1, 2, and

3 of this series appeared in the October, November. and December

1972 issues of Popular Electronics, respectively. See also "Nuclear

Radiation ... Insidious Polluter" in the February 1972 issue.

Part 3: How the Ionization Chamber, Proportional Counter,

and Geiger-Muller Tube Operate

Fig. 1 - Ionization chamber.

By J. G. Ello,

Radiation Measurements and Instrumentation Electronics Division, Argonne National

Laboratory

So far, we have discussed the phenomenon of radioactivity and found that the

three types of radiation are alpha and beta particles and gamma rays. Radiation

can ionize atoms. Since the ions have an electrical charge, they can be directed

in an electrical field to a positively-charged anode (collector) where they are

neutralized by supplying the positive ions with electrons from a battery, thus providing

a measurable current.

To make use of this detector current, a unit of measurement must be established.

Radiological survey meters measure radiation intensity in roentgens per hour (R/hr).

A roentgen is the intensity of gamma radiation that will reduce one electrostatic

unit of ions/cu cm of dry air, or the intensity of radiation that will produce a

little over 2 billion ion pairs/cu cm of dry air. The unit of measurement for detectable

radioactivity is called the roentgen, the order of magnitude most commonly used

is the milliroentgen, or mR.

As an example, a radioactive source is emitting an intensity of 2 mR/hr at a

point a certain distance from the source. If you were to stand at this distance

for one hour, you would receive a 2 mR/hr exposure. If the intensity were only 1

mR/hr and exposure time were extended to two hours, the radiation would be the same

since (1 mR/hr) (2 hr) = 2 mR.

Fig. 2 - Two views of ionization survey meter.

Fig. 3 - Schematic of ionization survey meter.

Ionization Detector

The construction of an ionization chamber

is quite simple. As shown in Fig. 1, it consists of an insulated central anode

enclosed by a shell of conducting material with an alpha window. The ionization

chambers used in many commercial survey meters are designed for only beta/gamma

radiation If alpha particles are to be detected, a very thin window is incorporated

into one end of the detector to allow the particles to pass into the detector. Most

alpha windows are made from 1-mil (0.001") thick Mylar with a coating of conducting

material on both sides. In some ionization survey meters, slide-type alpha and beta

absorbers are used to permit measuring beta particles in the presence of alpha particles

and gamma rays in the presence of beta articles.

An ionization survey meter is shown in Fig, 2. Through use of its built-in absorbers,

it can detect and measure alpha, beta, and gamma radiation. This is a self-contained

unit, powered by internal batteries. It consists of an ionization chamber, range

selector, amplifier, and dc microammeter. The alpha absorber is a 0.01"-thick cellulose

sheet, while the beta absorber is a 0.102"-thick plate of aluminum. Its range may

vary from about 5 mR/hr to 50 R/hr.

A simplified block diagram of the ionization survey meter is shown in Fig. 3.

The ionization detector is maintained at the proper voltage for operation in the

ionization-chamber region of the pulse-size/detector-voltage curve. As ions are

neutralized at the collector, a small ion-chamber current flows through the selected

range resistor. The pulse developed across this resistor is applied to the grid

of the amplifier tube or gate of a field-effect transistor. This minute current

is amplified and passed through the meter movement which is calibrated in mR/hr.

In use, the ionization chamber is located in the bottom forward position of the

instrument with the window on the bottom surface. To detect beta and gamma radiation

simultaneously, the aluminum absorber is pulled up; to detect alpha, beta, and gamma

radiation simultaneously, both absorber tabs are pulled up.

To check the unit's operation, an alpha or beta source is held close to the Mylar

window. With the survey meter adjusted to a suitable range, a reading should be

indicated on the meter. When making surveys, the unit would be moved across the

suspected material at about a 2 in./second scan and close to the material's surface

to obtain a true reading. Whenever a rapid jump of the meter pointer is observed,

radioactivity is most likely present in the material. To determine if it is gamma

radiation, both the alpha and beta absorbers should be in place. To read beta radiation,

the alpha absorber is left in place and the beta absorber is removed. To determine

beta intensity, the gamma reading is subtracted from the new reading. To check for

alpha radiation, both alpha and beta absorbers must be removed. Alpha intensity

is determined by subtracting the reading obtained for beta only from the new reading.

If no change is observed, there is no detectable alpha radiation present.

Proportional Detector

Although the ionization detector is ideal

for detecting the three types of radiation, it needs a very sensitive electrometer

tube or field-effect transistor amplifier stage. To eliminate the need for sensitive

amplifiers, detectors in which internal amplification takes place have been devised.

This amplification is referred to as the proportional region on the pulse-size /

detector-voltage curve. In this region, it is possible to differentiate between

alpha-, beta-, and gamma-generated pulses.

The internal amplification within the detector is caused by increasing the detector

voltage and, hence, the electrical field between the anode and cathode which causes

the electrons produced in the primary ionization of the atom to travel at higher

velocities. The primary electrons also have sufficient energy to dislodge other

electrons in their path and thereby generate larger pulses.

Fig. 4 - Air proportional detector.

Fig. 5 - An air proportional survey meter.

Shown in Fig. 4 is a basic sketch of an air proportional detector. It consists

of a 1-mil diameter center anode wire mounted on Teflon insulators. The alpha particle

window, fastened to the shell by an adhesive, is made from 0.25-mil thick Mylar.

The detector may consist of one center wire or as many as ten wires.

A battery-operated count-rate survey meter and its air proportional detector

are shown in Fig. 5. The detector has a metal screen to protect the alpha window

against punctures. It is called air proportional because it contains air instead

of a counting gas like that used in Geiger-Muller detectors. The detector is capable

of responding to all three types of radiation and, through the use of a discriminating

control, identify pulses produced by alpha particles and those produced by beta

particles.

The survey meter consists of an adjustable detector, high-voltage power supply,

range selector, amplifiers, discriminator, and count-rate circuit which supplies

current to the dc microammeter. The meter is calibrated in counts/minute instead

of mR/hr as in the ionization and Geiger-Muller survey meters.

The simplified block diagram of the survey meter is shown in Fig. 6. The

detector is set to operate in the proportional region by means of the detector voltage

supply. Pulses produced at the center wire (anode) are coupled to the grid of the

first amplifier stage and are then coupled to the second amplifier through the range

selector circuit. At the discriminator control, pulses of proper size are selected

and fed to the count rate circuit which supplies the dc current for the meter.

The average efficiency of an air proportional detector is about 10-15 percent;

the detector, therefore, is affected by only 10-15 percent of the total disintegration

taking place. For example, if a radioactive source disintegrates at a rate of 1000

disintegrations/minute (d/min), the detector "sees" about 100-150 d/min.

The surveying technique is the same as for ionization survey meters. The proportional

survey meter is used mainly in the field for alpha detection and measuring. If beta

and/or gamma radiation are to be measured, the discriminator control must be adjusted

to pass the smaller pulses they produce. In addition to gamma pulses, beta and alpha

pulses, if present, will also be indicated under these conditions. Hence, the unwanted

reading (in this case, the alpha reading) must be subtracted from the total reading.

Absorbers can also be used as in the ionization survey meters.

Fig. 6 - A simplified circuit diagram of an air proportional

survey meter.

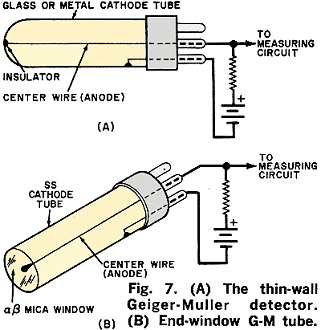

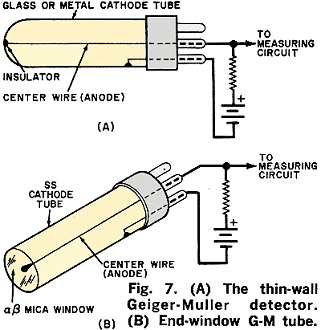

Fig. 7 - (A) The thin-wall Geiger-Muller detector. (B) End-window

G-M tube.

Geiger-Muller Detector

Often referred to as the "G-M tube,"

the Geiger-Muller detector is the most often used radiation detection instrument.

It operates in the Geiger-Muller region of the pulse-size/detector-voltage curve.

The main difference between the proportional detector and the G-M tube is that in

the former, the incident radiation produces an avalanche of electrons at only one

point in the detector, while in the latter, the electron avalanche spreads along

the entire length of the wire anode. The pulse size in the proportional detector

varies with the number of secondary electrons produced. In the G-M tube, electron

amplification is much larger so that the pulse size is practically independent of

the number of electrons produced per nuclear radiation incident. The G-M tube, therefore,

cannot discriminate between types of radiation.

The larger pulse size is due to the high electrical field and the fact that the

G-M tube is filled with a counting gas, such as neon plus halogen, instead of air.

This provides an additional electron amplification factor, referred to as "gas amplification."

The main advantage of gas amplification is that the detector itself requires less

external amplification.

Shown in Fig. 7 A is a basic thin-wall G-M tube, while Fig. 7B depicts

a basic end-window G-M tube. The cathode is stainless steel or glass tubing with

a conductive coating on the inside.

To detect alpha radiation, the wall of the tube must be very thin. For this application,

the G-M detector is fabricated with a very thin window as shown in Fig. 7B.

The cathode material, usually made from stainless steel, is about 0.003" thick,

mainly for strength. The end window is made from very thin mica. The center wire

is supported only at the base end, while the free end is tipped with a glass bead

to prevent spurious internal discharges.

In Fig. 8 are shown two battery-powered G-M survey meters. The end-window

G-M survey meter is at the left; a thin-wall G-M meter is on the right. Both instruments

contain a high-voltage detector supply, amplifier and trigger stages, and a drive

circuit for the dc microammeter. Like the proportional survey meter, an audio jack

is provided for aural monitoring.

A simplified block diagram of a G-M survey meter is shown in Fig. 9. The

detector is maintained at a fixed voltage to operate in the Geiger-Muller region

of the pulse-size/detector-voltage curve. Due to the detector gas electron amplification,

a pulse amplifier is not required; detector pulses are coupled directly to a two-tube

trigger circuit which modifies the pulse sizes and feeds them to the metering circuit

which is calibrated in mR/hr. The coupling between the trigger tubes serves as the

range selector.

The walls and mica windows of the G-M tube are very thin; so, care must he exercised

to avoid any physical shock to the detector. Unlike an ionization survey meter which

can work if the detector's window is ruptured, G-M detectors become inoperative

if the wall or window is damaged.

Another limitation of G-M detectors is their inability to respond indefinitely

to radiation, which can be done by ionization and air proportional detectors. The

normal life of a G-M tube is about a billion counts, after which efficiency drops

off. Many G-M tubes cease to give any indication and may read zero mR/hr when exposed

to a very high radiation intensity.

Fig. 8 - (Left) End-window and (right) thin-wall Geiger-Muller

survey meters.

Fig. 9 - Basic diagram of G-M survey meter.

Scintillation Detector

Another type of detector used in surveying

radioactivity is known as the "scintillation detector." It is made from a phosphorescent

material which gives off flashes of light called scintillations, when exposed to

nuclear radiation. Modern scintillation materials are in the form of crystals, liquids,

or gases. The most widely used at the present time is a sodium iodide crystal, optically

coupled to a #6292 photo-multiplier tube.

When exposed to nuclear radiation, the. scintillator gives off a glow which is

converted into electrical pulses by the photo-multiplier tube. The scintillation

detector consists of an optical coupling system contained inside a light-tight package.

To detect alpha and beta particles, the housing must have a very thin opaque window

to exclude all outside light while passing only the radiation particles.

The magnitude of the electrical pulses generated by the scintillations is proportional

to the energy of the radiation. In most cases, the pulse information is analyzed

in a multichannel pulse-light analyzer to identify nuclear radiation by type. In

addition, the scintillation detector can operate in counting ranges many times higher

than the G-M detector.

Solid-State Detector

One of the newer developments in radiation

detection is the solid-state detector. It operates on basically the same principle

as the G-M tube and ionization detector except that it employs a semiconductor material

such as silicon instead of a gas for the counting material. When employed as a detector,

the silicon is in a highly purified state and, like other detectors, is sensitive

to and can measure energy levels of alpha, beta, and gamma radiation.

Silicon diode detectors can be made very small, so small in fact that they can

be mounted in hypodermic needles. Most detectors, however, measure about 1" in diameter

by 1/16" thick. They are used mainly in the health physics field for counting airborne

radioactive particles.

Non-electronic Detectors. Radiological survey meters discussed above are electronic

instruments used for measuring radiation intensity at a given moment in time. There

are, however, devices which measure the total accumulated radiation dosage to which

an object is exposed over a period of time (as short as a few minutes or as much

as a week or more).

The self-indicating dosimeter is basically a miniature ionization chamber made

in the form of a fountain pen. It contains a capacitor which is originally charged

up to a fixed voltage. When exposed to radiation the ions formed in the chamber

remove some of the capacitor's charge and reduce the voltage. The voltage charge

remaining is measured by a movable quartz fiber built into the unit. An internal

scale, when held to the light and viewed through a lens magnifier, indicates this

voltage drop in mR/hr.

Another type of dosimeter employs the radioluminescence phenomenon. Called a

thermoluminescent dosimeter, it works in a manner similar to the scintillation detector.

However, external equipment is needed to "develop" the indicating medium and to

count the accumulated radiation intensity received.

One of the oldest known types of detectors is the film badge. The radiation received

on exposure causes the film to darken in proportion to the amount received. Special

film badges have been developed for low-energy beta, gamma, X-ray, and neutron types

of radiation. Detection of alpha particles is virtually impossible due to the fact

that the film must be packaged in an opaque container. External equipment is needed

for developing and interpreting the film's information.

Posted July 5, 2024

(updated from original post

on 7/20/2017)

|