|

November 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Part 1 of this 3-part

series discussed the basics of nuclear radiation, and now here in Part 2, author Ello delves into various

methods of detecting and measuring radiation levels. Ionizing radiation measurement

capability is needed for the safety of life forms due its ability to knock electrons

away from their host atoms, thus generating ions that cause molecules to form that

might not otherwise do so. If those molecules happen to part of a self-reproducing

living cell, then a mutant - or cancerous - cell is the result. With luck, body

defense cells will hunt down and kill it, but if not, a tumor will develop - maybe

benign, but maybe malignant.

Parts

1, 2, and

3 of this series appeared in the October, November, and December

1972 issues of Popular Electronics, respectively. See also "Nuclear

Radiation ... Insidious Polluter" in the February 1972 issue.

Nuclear Radiation & Detection - Part 2

Ionization and How Ionization Current is

Detected Ionization and How Ionization Current is

Detected

By J. G. Ello, Radiation Measurements and Instrumentation

Electronics Division, Argonne National Laboratory

In Part 1 of this series, the various types of radioactivity and the behavior

of each were discussed. Before getting into the details of radiation detection,

the topic of Part 2, a review of the characteristics of the three types of radiation

is in order.

In Part 1, it was stated that the alpha particle's large mass and high velocity

contribute to its good ionizing power. Because its penetrating power is weak, the

alpha particle is easily absorbed by a few sheets of newspaper. And, being a particle

with a positive charge, it can be deflected in a magnetic field.

The beta particle has more penetrating power and achieves a greater velocity

than the alpha particle. Because of its negative charge, it can be deflected in

a magnetic field, but in the opposite direction to that of the alpha particle. The

beta particle has less ionizing power than the alpha particle, but its penetrating

power is greater, a thin sheet of aluminum or Lucite being required to absorb the

particle.

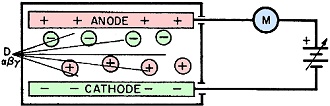

Fig. 1. Ion-pair production is the result of alpha particle

striking atom.

Because they are electromagnetic waves - not particles - and without an electrical

charge, gamma rays cannot be deflected in a magnetic field. Gamma rays travel at

the velocity of light and are highly penetrative. It may take several inches of

lead or 3 or 4 feet of concrete to absorb them. Of the three types of radiation,

the gamma ray has the least ionizing power.

Ionization

When it passes through matter or gases like air,

nuclear radiation produces ion pairs. The manner in which ion pairs are formed by

an alpha particle colliding with an oxygen atom is shown in Fig. 1. The electron

dislodged by the alpha particle becomes a negative ion, while the remainder of the

atom, now minus one electron, becomes a positive ion. Note that the collision forms

two oppositely charged ions; hence the term "ion pair."

The alpha particle continues to produce ion pairs until it has lost all its energy

through collisions. The process may result in more than 100,000 ion pairs in a cubic

centimeter of air. In a similar manner, a beta particle produces ions, but only

at a rate of about 300 ion pairs per cubic centimeter of air.

Gamma and X rays which are not particles also produce ion pairs, but in a slightly

different manner. Gamma rays can eject electrons from atoms with sufficient velocity

to make them collide with other atoms to produce ion pairs. The number of ion pairs

thus formed depends on the energy of the freed electrons.

Ion pairs made from neutral atoms move about in random paths until, through recombination,

they eventually become neutral atoms again. However, if ions are produced in an

electrical field, they are affected by the field.

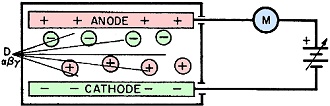

Consider a small chamber with one set of parallel plates (electrodes) on the

inside. It is being irradiated by a beta ray source as shown in Fig. 2. With

the power switch open as in A, no electrical field is applied to the electrodes.

In the absence of an electrical field, the ions will recombine to form neutral atoms

(as a result of the attraction of opposite charges). However, when the switch is

closed as in B, an electrical field is generated between the electrodes. This forces

the ions to move in opposite directions, the negative ions to the positive electrode

and the positive ions to the negative electrode. Eventually, as shown in C, the

ions become neutralized since the positive ions attract negative ions from the negative

electrode and the negative ions give up their charge at the positive electrode.

Fig. 2. Neutralization of ions is shown.

Fig. 3. Ionization current measurement.

Detecting Ionization Current

The basic scheme shown in Fig. 3

is an example of a radiation detector. Attached to the detector, in series with

a sensitive ionization pulse current meter, is a power supply which can be varied

from zero to some high voltage.

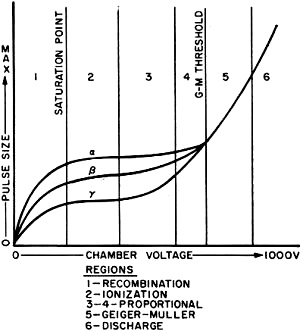

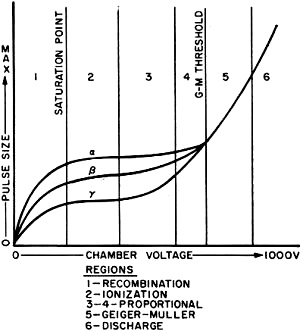

The effect of the detector voltage on neutralizing ion pairs in six different

regions is shown in the graph in Fig. 4. The three curves show that an alpha

particle ionizes more atoms in its path than do the beta particle and gamma ray.

Assume that the detector chamber which contains a counting gas (Fig. 3)

is exposed to a radioactive source with the detector voltage set to zero. There

is no electrical field to accelerate the ions which wander about and eventually

recombine. Hence, no meter pointer deflection will be observed.

Now, when a low voltage is applied to the detector, creating a weak electrical

field between the anode and cathode, a small portion of the negative ions is neutralized

or collected at the anode. However, slower moving ions have ample time to recombine

before reaching the anode, and the pulse size is smaller. This partial collection

of ions takes place in the recombination region on the graph.

Raising the detector voltage increases the electrical field and accelerates the

ions, lessening ion recombination and permitting more ions to be collected by the

anode. By further increasing the voltage, a point is reached at which the ionization

current is proportional to the detector voltage and all ions are collected as fast

as they are produced. This occurs at the "saturation point" on the graph and places

the detector operating characteristics in the ionization region. Any additional

increase in detector voltage in this region will not increase the ionization current

because only ions formed by the radioactive particles contribute to the ionization

current flow in the detector.

Beyond the ionization region (flat portion of the curve), any additional increase

in detector voltage will result in an increase in detector ionization current. This

is evidence that some new phenomenon is taking place within the detector. Since

the voltage has been increased, the electrical field has been increased which accelerates

the ions toward the anode at a much greater velocity. The negative ion, or electron,

with its higher velocity, has enough energy to dislodge other electrons, creating

additional ion pairs which contribute to the total ionization current. This secondary

electron region is shown on the curve as the proportional regions.

In the proportional regions, under ideal conditions, it is possible to differentiate

between alpha, beta, and gamma ionization current pulses as shown on the graph.

Instruments which use this portion of the curves are known as proportional counters.

Fig. 4. Chamber voltage vs. pulse size.

In the Geiger-Muller region on the graph, the detector's voltage is increased

to a level sufficient to cause an avalanche of freed electrons. For example, one

alpha or beta particle or gamma ray will ionize an air atom with so much energy

that a freed electron is capable of freeing another electron and these, in turn,

free other electrons to create an avalanche effect. This electron multiplication

reaches a point at which all ionization current pulses are equal in amplitude (G-M

threshold point where all curves join to form a single curve on the graph). Radiological

instruments operated in this region are known as Geiger-Muller survey meters.

The last section of the graph is the continuous discharge region. Here, the detector's

voltage is so high that once an ionization takes place, there is a continuous discharge

of electricity like an arc across the gap between the anode and the cathode. Consequently,

this region is of no use at all for detection of radioactivity.

Next month in Part 3 in this series, we will discuss the use of the counting

regions in various radiological survey meters.

Posted March 12, 2024

(updated from original post

on 9/22/2017)

|