May 1961 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

"What are these devices?"

"How do they work?" "What are their characteristics?" "How are they used?" Those

are the kinds of questions about semiconductor diodes posed - and answered - in

this article in a 1961 issue of Popular Electronics. Author Jim Kyle runs

through a short history of he diode and then delves with more detail into physical

construction, I-V curves, power handling, junctions capacitance, resistance, etc.

An interesting point mentioned is that while a semiconductor diode will conduct

some finite amount of current when biased in the reverse direction (sometimes a

desired characteristic), a vacuum tube diode will not conduct at all when reverse

biased - thereby making the tube a more perfect rectifier.

Electronics magazines of the era published many articles about selenium

rectifiers, including

After Class: Working with Selenium Rectifiers,

The Semiconductor Diode,

New Selenium Rectifiers for Home Receivers,

Selenium Rectifiers,

Applications of Small High-Voltage Selenium Rectifiers, and

Using

Selenium Rectifiers.

The Semiconductor Diode - What It Is. How It Works. What

It Does.

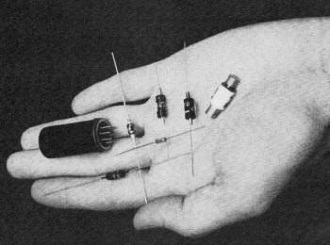

A variety of semiconductor diode.

By Jim Kyle, KSJKX/6

A seven story high intercontinental missile roars skyward on a column of

fire. Within the silvery giant, hundreds of tiny semiconductor diodes control its

every movement.

A television camera is focused on a man. Millions of viewers are watching. Between

the man and the millions of viewers are dozens of semiconductor diodes - without

them television could not function.

Older than radio itself, and once thought obsolete, semiconductor diodes today

are the workhorses of the electronics industry. They form the heart of nearly all

digital computers - the giant electronic brains that can predict an election outcome

or control a manufacturing plant. They make radar possible. They detect radio signals,

and, on occasion, generate those same signals.

What are these devices? How do they work? What are their characteristics? How

are they used?

In essence, the answers are simple. First of all, a semiconductor diode is a

one-way street for electric currents. It will allow the current to flow freely in

one direction, but will block it almost completely in the other. Because of this

characteristic, the semiconductor diode can perform a wide variety of jobs and is

one of our most basic electronic servants.

How the Diode Works

To understand how a semiconductor diode works, let's go back a bit and examine

electricity itself. An electric current is simply another name for a flow of electrons

- the basic electrical charge found in all elements. Electricity flows when electrons

move from one atom of a substance to the next.

In some materials - copper, silver, aluminum, and many other metals - the electrons

can move easily. These substances are called conductors.

In other materials - glass, porcelain, hard rubber, and many plastics - the electrons

can move only with great difficulty. In fact, only a very few electrons can move

at all in these substances, even under great electrical pressure; and so flow of

electric current through them is blocked. We call these substances insulators.

Between conductors and insulators are many materials which are neither good conductors

nor acceptable insulators. The electrons of their atoms are free to move, but are

not so free as in a conductor. These substances are known as semiconductors.

Types of Semiconductors

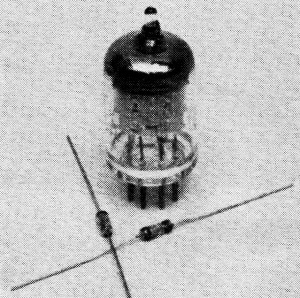

Selenium rectifiers, in use for over 25 years, are giving way

to smaller silicon diodes such as Sarkes-Tarzian's 1N1083.

Fig. 1 - Diode current measurement.

Although many semiconductors exist (most materials fall into this classification),

only a few are used in electronics. Those most widely used are germanium, silicon,

selenium, and copper oxide. In past years, galena (a form of lead oxide) was also

used.

These particular semiconductors have a strange property. Under certain special

conditions, electrons can flow out of them easier than in. Under other conditions,

the situation is reversed: electrons come in freely, but have difficulty getting

out.

Since this strange property makes itself evident only when electrons enter or

leave the semiconductor material, it is useful only when the semiconductor is in

contact with a conductor. This contact may be made in two ways: by point contact,

in which the semiconductor and the conductor make contact at only a single point;

and by surface contact, in which they meet over a broad area. Each way has its advantages.

An early example of point-contact use is the old-fashioned crystal set. Invented

about 1906 by two experimenters named H. H. Dunwoody and G. W. Pickard, this was

the mainstay of radio for nearly 20 years. It consisted of a small piece of galena

crystal and a spring-wire "cat-whisker." The user moved the cat-whisker over the

surface of the crystal until a sensitive spot was located.

An example of surface-contact application is the copper-oxide stack, widely used

in both test equipment and in telephone engineering. Developed about 1925, this

device consists of alternate discs of lead and copper oxide, stacked face-to-face

and held together by an insulated bolt through the center. It requires no adjustment.

However, technical limitations restrict its use.

Another example of surface-contact diodes is the modern grown-junction unit,

such as the 1N34 so widely used by experimenters.

Electron Flow. At this point, let's narrow the field down to

a typical point-contact unit such as the crystal set and take a look at what happens

when this semiconductor diode is connected to a battery and a meter. See Fig. 1.

When the battery is connected, its voltage forces electrons of the interconnecting

wire into the semiconductor, across the contact point, into the conductor, through

the meter, and back through the other interconnecting wire into the battery.

You can see that with the battery connected in one direction, electrons are forced

out of the semiconductor at the contact point. If the battery's polarity is reversed,

electrons will be forced into the semiconductor.

Let's assume that this particular diode is made from a semiconductor that is

stingy with electrons; that is, it accepts electrons readily, but doesn't let go

of them so easily.

When the battery is connected in the first direction, forcing electrons out of

the semiconductor at the contact point, the semiconductor material exhibits great

resistance. Only a few electrons are released to travel on through the meter and

back to the battery, and so only a small current flows.

However, when the battery is reversed, we're pushing electrons into our greedy

semiconductor, and it readily accepts all we can offer. Many electrons move through

the meter, or, in other words, a large current flows.

Only the action at the contact point is important; the other electrical connection

to the semiconductor material covers a much larger area and, since resistance is

proportional to area, has much lower resistance. However, it does contribute to

the diode's forward resistance, which we'll talk about more a bit later.

If a different semiconductor - one that is generous instead of miserly - is used,

the situation will be exactly opposite to that described above. However, the diode

would still be a one-way street. The only difference is that it would be one-way

in the other direction.

Two low-cost diodes replace 6AL5 vacuum tube, saving filament

power and space.

Fig. 2 - Electron flow through a diode, cathode to anode.

This one-way-street action is similar in effect to the action of a diode vacuum

tube, such as the familiar type 5U4-G. In the vacuum tube, heat generated in the

filament causes electrons to literally boil off its surface. When the plate of the

tube is made positive, the electrons flow to it. However, since like charges repel

each other, the electrons will not go to the plate when it is negative.

Pros and Cons. In both the semiconductor diode and its vacuum-tube

cousins, current flows readily in only one direction. This property makes them useful

in changing a.c. to d.c., and they are widely used in electronic power supplies

for this reason.

A great advantage of the semiconductor diode over its vacuum-tube cousins is

that the semiconductor version does not require heat to move its electrons. This

eliminates the hot and power-wasting filament.

Another advantage is the smaller size possible with semiconductors. Typical semiconductor

diodes are no bigger around than a pencil, and less than an inch long - compared

to the 3/4" diameter and 1 1/4" length of the smallest standard vacuum diodes.

Another point of difference between the semiconductor diode and its vacuum-tube

cousins - but it's not usually considered an advantage - is the matter of reverse

current.

In the semiconductor diode, current flows more easily in one direction than in

the other. However, in the vacuum-tube version, current can flow only in one direction.

While the semiconductor diode is like a one-way street for electrons, the vacuum

diode is more like a subway turnstile. You can go the wrong way on a one-way street;

you can't go the wrong way through a turnstile.

While this might look like a big disadvantage for the semiconductor diode, it

usually isn't harmful in practice. Present-day diodes may pass a million times as

much current in one direction as in the other; the small number of electrons which

get though the wrong way have little or no effect on diode operation.

Since the point-contact diode is the oldest type, the standard schematic symbol

for a semiconductor diode is based on it. See Fig. 2.

Regardless of whether the semiconductor is stingy or generous with electrons,

the arrow of the symbol points against the flow of traffic in our one-way street.

This confusing situation came about in earlier years, before scientists had learned

as much about the diode as they know today. The original direction for the arrow

was chosen arbitrarily, and the symbol had been in use for some time before they

discovered the arrow was pointing the wrong way!

Characteristics

The main property of a semiconductor diode is that it will pass current easily

in one direction, and will allow only a small amount of current to flow the other

way. The easy-current direction is usually called forward, while the other direction,

quite naturally, is called reverse.

Current. One of the basic characteristics on which these diodes are rated is

the amount of current which the unit will let through in each direction. The ratings

are listed in terms of forward current and reverse current. Forward current, i.e.,

current going in the easy direction, is always the larger of the two. Frequently

forward current is measured in hundreds of milliamperes while reverse current is

given in microamperes.

Another way of looking at these diodes is to examine their resistance. Since

resistance (in ohms) is equal to the applied voltage divided by the current (in

amperes) which flows through the circuit, you can see that resistance in the forward

direction is much lower than resistance in the reverse direction. The more common

way of putting this is to say that forward resistance of a semiconductor diode is

low while reverse or back resistance is high.

Resistance

However, semiconductor diodes have an unusual resistance characteristic. Their

resistance varies in accordance with the voltage you apply to them. At low voltages,

forward resistance is high; at higher voltages, it drops. Reverse resistance, on

the other hand, is extremely high at low voltages, but drops to zero or even exhibits

negative characteristics at some critical point as voltage increases.

The critical point at which reverse resistance tends to disappear is called the

diode's peak inverse voltage (usually abbreviated PIV) and is a key characteristic

of power rectifiers.

Engineers call a resistance characteristic of a semiconductor diode nonlinear,

because the plotted line on a graph comparing voltage against current appears as

a curve instead of a straight line. The nonlinear resistance of the semiconductor

diode makes it useful as a detector, as a mixer, and as a modulator; however, the

nonlinear resistance also makes it difficult to specify any other diode characteristic.

For instance, a vacuum diode can be rated for 300 milliamperes of current, and this

will be true at any voltage. Before a semiconductor diode can be rated, however,

you must specify the voltage.

The same is true of the all-important reverse resistance rating. The same diode

may have a reverse resistance of one megohm, less than an ohm, or even negative

100 ohms, depending entirely upon the voltage at which the reading is taken.

Voltage

Fig. 3 - Semiconductor diode I-V curve.

Power rectifier diodes come equipped with screw studs for mounting

to heat sinks. Unit shown here is rated at 70 amperes.

All diode characteristics, therefore, are given in terms of current at some specified

voltage. Different manufacturers use different voltages, and to complicate things

still more, some firms rate different diodes at different voltages. This makes comparison

of two diodes, on the basis of rated characteristics, almost impossible unless both

are rated under the same conditions.

Manufacturers of diodes, however, furnish another item which can help you avoid

this problem - the characteristic curve of the diode. See Fig. 3.

The vertical scale in Fig. 3 shows current; the horizontal scale, voltage.

Note that forward voltages and currents are expressed in larger units than are reverse

values; this is customary in the preparation of diode characteristic curves.

With a set of characteristic curves, you can determine the characteristics of

a diode at any operating point. Simply look up the current value for the voltage

you intend to use, and determine the resistance by using Ohm's law. To compare two

different diodes, compare the shape of the curves.

Bias

A term worth mentioning at this point, since you'll hear it frequently in dealing

with semiconductor diodes, is bias. Bias consists of a voltage applied to a diode

to make it operate at the point desired by the designer. If the voltage applied

causes forward current to flow, it's called forward bias. If it's applied in the

reverse direction, the term is reverse bias. A diode to which such a voltage is

applied is said to be biased.

In addition to the major characteristics which we've examined so far - forward

current, reverse current, forward resistance, reverse resistance, and peak inverse

voltage - semiconductor diodes have two more important characteristics. They are

the thermal character-istic and diode capacitance.

Temperature

"Thermal characteristic" simply is a fancy way of saying "how heat affects the

diode." We stated earlier that in the vacuum-tube diode electrons were boiled off

the filament by heat. Actually, heat increases the movement of all electrons, something

like popcorn on a hot stove. At high temperatures, the electrons move more freely.

Up to a certain point, heat has little effect on a semiconductor diode. Although

reverse current increases slightly, forward current increases in the same ratio.

At the critical temperature, however, the crystal structure breaks down and current

flows just as freely in either direction. Some diodes recover when they are cooled,

while others are ruined for good.

The manufacturer usually rates his product to be used within a certain temperature

range, and this range is generally far greater than the temperatures at which you

are likely to use it (a typical operating range is from 40 degrees below zero to

300 degrees above). However, if excessive current is sent through the diode in either

direction, it may heat - internally - to a point far above the critical breakdown

temperature. This is the most frequent cause of diode failure.

Capacitance

The last major characteristic is diode capacitance. A capacitor, by definition,

is made up of two conductors separated by a dielectric. Thus, the semiconductor

material itself can be the dielectric of a capacitor whose plates are the conductors

on either side.

Actually, the physicists tell us, most semiconductor diodes show a greater capacitance

than we would expect, due to something called the barrier effect. This is a function

of the applied voltage. As a result, the capacitance of a semiconductor diode changes

with the voltage in a manner similar to the diode's resistance.

This capacitance has little effect on forward resistance or forward current,

since the diode is conducting and the capacitance is shorted out. However, the diode's

capacitance can be important when the diode is not conducting, since the capacitance

will allow very-high-frequency alternating currents to pass.

Most semiconductor diodes have a capacitance in the neighborhood of 3 to 5 μμf.

Those diodes built especially for use at radar frequencies have even less capacitance.

How Diodes Are Used

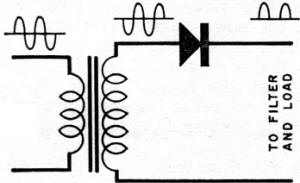

Fig. 4 - Half-wave diode rectifier.

Fig. 5 - Full-wave diode rectifier.

Of what practical use is the semiconductor diode's one-way-street property? One

of the more obvious applications is in changing alternating current into direct

current, such as in a receiver's power supply. The diode is simply connected in

series with the a.c. coming from the transformer. Those half-cycles which constitute

forward voltage go through the diode into the filter circuit, while half-cycles

of inverse voltage are blocked.

Half-Wave Rectifier

The circuit in Fig. 4, called a half-wave rectifier, is the simplest possible,

but it is hardly the most efficient. Half of the a.c. power is not used. However,

by connecting three additional diodes into a "bridge" circuit, the half-cycles of

opposite-polarity a.c. can be steered in the proper directions so that both halves

of each cycle are used and yet the power supplied to the filter is direct current.

Refer to Fig. 5.

When the voltage at point A in Fig. 5 is positive, the voltage at point

B will be negative, since the supply voltage is alternating. The electrons flow

from point B through diode D2 to the filter and load circuit, and are blocked at

D3 and D4 since their reverse resistance is high. From the load and filter, the

electrons return through diode D1 to point A.

On the other half-cycle, electrons flow from point A through diode D4 to the

filter - being blocked at diodes D1 and D2 by the reverse resistance - then return

to point B through D3.

Other rectifier circuits using more than one diode are popular. They include

voltage multipliers which make it possible to obtain as much as 1000 volts of direct

current from a 117-volt power line without using transformers, dual-voltage circuits

which provide two different direct voltages from one transformer, and "bias-supply"

circuits which can be made to fit into less space than a conventional vacuum-tube

rectifier alone.

The semiconductor diode most widely used for power supply rectifiers is the selenium

stack. However, silicon junction diodes capable of handling four to five times the

current of the selenium stack in one-tenth the space are rapidly becoming popular.

Diode Detector

Small semiconductor diodes have axial leads, eliminating

the need for sockets.

Fig. 6 - Diode AND gate.

The semiconductor diode also finds wide use in radio receivers, television sets,

radar, and test equipment, as a detector of r.f. power.

The circuit of the diode detector is identical to that of the half-wave rectifier

- it contains a source of power, the diode, and a load, all connected in series.

However, the operation is slightly different.

During each cycle of r.f. energy, the diode allows current to pass in the forward

direction but blocks the flow of reverse current. The current flowing in the forward

direction produces a voltage drop in the load resistor which is paralleled with

a low-value capacitor. If the strength of the r.f. power is changing, the d.c. voltage

across the load resistor will change at the same rate. And if this change occurs

at an audio frequency, the voltage across the load resistor will vary at the same

a.f. rate.

The average strength of the d.c. voltage across the detector load resistor is

proportional to the average strength of the r.f. voltage applied to the circuit.

In radio receivers, this effect is used to provide automatic volume control, while

in test equipment it is used to measure r.f. with a conventional d.c. voltmeter.

Vacuum-tube diodes, which operate in similar fashion, can be used for these purposes

at moderately high frequencies. However, at the extremely high frequencies used

in radar, they fail to function properly. Here, the semiconductor diode's very low

capacitance makes it the only usable detector.

Computer Circuits. A few paragraphs earlier, we met the bridge

rectifier circuit, and saw how the semiconductor diode was capable of steering an

incoming signal into one of several directions. This property is widely used in

computer circuitry, where the proper combination of diodes can actually make logical

decisions.

A basic circuit of this type is shown in Fig. 6. This circuit is exceptionally

choosy - it will produce an output signal only if you give it signals at both of

its inputs. If you give it a signal at only one of the input terminals, it produces

nothing. This is called a logical "and" circuit, since it must have both signal

A and signal B to provide an output. Another way of putting it is to say that the

circuit must decide whether both inputs are present before deciding to produce an

output.

With no input signals applied, both diodes are biased in the forward direction

by the positive voltage through R2; R1's value is very much less than that of R2,

so the output is nearly zero. With a positive input signal applied to either A or

B but not to both, the diode without an input signal still shorts the voltage from

R2 through R1 to ground and no output is developed. However, with positive input

signals applied to both A and B at the same time, both diodes are biased in the

reverse direction. Current through R2 meets the high reverse resistance of the diodes,

and in consequence is shunted through the output circuit.

Typical values for R1 and R2 are 10 ohms and 10,000 ohms, respectively. The voltage

source is usually about 12 volts.

Similar circuits are used to develop outputs if a signal is applied to either

input; to develop output if a signal is applied to either input but not to both;

and to develop output at all times except when a signal is applied to both inputs.

Circuits such as these form the basis of many of the giant computers. Each circuit

is simple enough, but a typical computer may contain literally thousands of them.

The semiconductor diode makes this possible; if you were to try to use vacuum diodes

in its place, you would find that filament power requirements alone would mount

to hundreds of kilowatts!

Automatic Noise Limiter

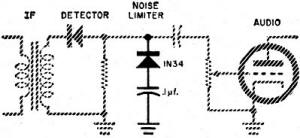

Fig. 7 - Diode noise limiter.

Another use of the semiconductor diode's "gating" ability is in the automatic

noise limiter found in many ham-type radio receivers. The purpose of the noise limiter

is to steer the desired audio signals to the loudspeaker, and to gate any noise

bursts caused by passing cars or by static crashes to ground.

While dozens of noise-limiter circuits exist, the circuit shown in Fig. 7

is one of the simplest and is unusually effective on many types of noise.

With no noise, the limiter diode is forward-biased by the d.c. voltage developed

across the detector load resistor, and it conducts until the capacitor charges to

the value of this voltage. At this point, the bias on the limiter diode drops to

zero.

Remember that when we were discussing the nonlinear resistance of the diode,

we found it had high forward resistance at low voltages, and low resistance at higher

voltages? With no noise, and consequently no bias, the diode's resistance is high

and the capacitor is effectively out of the audio circuit.

However, when a noise pulse - whose voltage is much higher than the average signal

- comes along, the picture changes. The diode is once more biased to a low-resistance

point, and gates the noise pulse through the capacitor to ground. As soon as the

pulse is gone, diode resistance returns to its normal high value.

Mixers

Semiconductor diodes are also widely used as mixers in extremely high frequency

superhet receivers, such as radar and microwave-relay sets. In this application,

they outperform any available tube. In fact, much of the progress that separates

today's semiconductor diodes from the ancient crystal set can be traced to World

War II development of the diode for use in radar sets as the mixer element.

A complete explanation of this form of diode operation requires pages of mathematical

equations; in simplified form, this is how it works:

The diode is connected to the antenna of the set, and is also connected to a

local oscillator whose frequency is separated from that of the incoming signal by

some small, desired amount. Signals coming from the antenna mix, in the diode, with

those from the local oscillator.

The diode's output, you can see, will consist of pulses of direct current occurring

on each half-cycle of the antenna signal, and other pulses every half-cycle of the

local-oscillator signal. In addition, however, two new signals are created. Their

frequencies are equal to the sum and the difference of the antenna and local-oscillator

signals, and their strength is proportional to the product of the two input signals.

Since only the incoming antenna signal is changing in strength, the difference

signal will be a replica of the antenna signal but at a lower frequency. Thus, the

tricky microwave signal is converted to a lower frequency signal which can be handled

by more conventional means.

Semiconductor diodes excel as microwave mixers because of their extremely low

capacitance. Other types of mixer circuits fail to operate at frequencies higher

than about 900 megacycles, but semiconductor diode mixers continue to operate up

to 30,000 mc., and some new types promise to work at even higher frequencies.

Special Uses

Packaging of diodes in tube shells permits replacement of 5U4,

5W4, 5Y3, 6X4 and other rectifiers. Cartridge-cased diodes are used in the newer

TV sets.

Many special-use circuits have been developed around semiconductor diodes. Telephone

engineers use diodes as modulators, making use of the nonlinear resistance. Under

certain conditions, the resistance of a diode can become negative - and it can then

be used as an oscillator. Under other conditions, diode capacitance can be varied

at an extremely rapid rate - and this leads to the "parametric amplifier" which

makes possible communication by moon-bounce and radar contact with distant planets.

"Special" Diodes. The many uses we've listed so far for the

semiconductor diode barely begin to show the variety of jobs to which this electronic

workhorse is hitched daily. In addition to conventional diodes such as we have discussed,

there are dozens of "special" diodes in which one characteristic or another is stressed,

and more new types are being developed every month.

Among these "special" diodes are the tunnel diode, which operates at speeds near

that of light; the Zener diode, which can regulate voltages in the same manner as

a VR tube; and the voltage-variable capacitor - which is really a diode at heart.

Yes, the semiconductor diode has traveled a long way since its original discovery

in 1874, 13 years before Dr. Heinrich Hertz discovered radio itself. From the primitive

crystal set and crude copper-oxide stacks, through the sealed-unit microwave mixers

of World War II and into the era of the junction diode (announced in 1948), it has

been one of the most basic, most useful, and least understood of our electronic

servants. Over-shadowed in the early 1920's by its bigger and hotter rival, the

vacuum tube, the semiconductor diode is only now regaining its place-as electrons'

one-way street.

Posted January 24, 2022

(updated from original post on 6/1/2014)

|