|

April 1967 Popular Electronics

Table

of Contents Table

of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

In 1967 when this article

article appeared in Popular Electronics magazine, the use of integrated

circuits in consumer electronics was still relatively new. RCA, GE, Westinghouse,

and Philco had just released their first TVs and radios with IC front ends, and

Heathkit even had a build-it-yourself model. The military was using them (ICs) in

proximity fuse designs. The new technology was really cooking. ESD issues were discovered

and needed to be dealt with as gate sizes shrunk and the vulnerability to arcing

became a problem. A photo is shown where NASA developed a method for mitigating

the potential damage by looping a spring-loaded wire around the leads of MOS-based

ICs during handling. A bit of nerd humor is also presented to commemorate the April

edition.

Solid State columns: April 1967,

August 1967,

April 1966,

August 1970,

July 1971,

October 1971,

April 1972.

Solid State

A new manufacturing process at Eburn Industrial Research Corp.

(Hingham, Mass.) allows IC designers to pack 100 times as much circuitry into the

same area occupied by a conventional transistor.

Fig. 1 - Two-transistor AM broadcast-band receiver circuit

submitted by reader Doug Zimmer features a Darlington pair amplifier (Q1 and Q2),

and a power switch that lets you select either a chemical battery, B1, or a sun-powered

battery (PC1).

Fig. 2 - One of the many practical FET circuits described

in a recent folder from Siliconix, Inc., each stage of this phase shifter permits

continuous adjustment of phase shifts from 0°·to 180°.

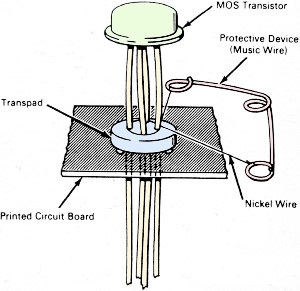

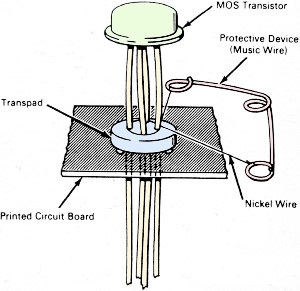

Fig. 3 - This is a simple device used by NASA to protect

MOS transistors from being accidentally damaged by the application of an electrostatic

potential across the leads while the transistor is being handled or assembled in

a circuit. A loop of flexible nickel wire is attached to a music wire spring that

is slipped over the transistor's case and released, shorting together all of the

leads.

Oversize Power Transistor

On April 1, the Lou Garner Enterprises announced the development

of the BMB transistor. Rated at a maximum free air dissipation of about 10,000 watts,

the new transistor is shown in the accompanying photograph - note how the elements

dwarf the nut and crescent wrench. Beta values have not been calculated, but the

alpha is reported to be close to 1.0001 under typical operating conditions. Distribution

and quantity prices have not yet been firmly established for this breakthrough.

Withdrawn from Market

Due to production and patent problems, the Lou Garner Enterprises

on April 2 regretfully announced the withdrawal of the super-power transistor. Interest

in this new development was confined to April Fool's Day.

By Lou Garner, Semiconductor Editor By Lou Garner, Semiconductor Editor

The use of integrated circuits in consumer products is increasing at an accelerated

pace. Last year several major manufacturers started to include IC devices in their

TV sets (RCA) and table-model radio receivers (GE and Philco). Heath followed suit

shortly thereafter with a TV receiver kit featuring an IC. H.H. Scott a major hi-fi

equipment producer, is now using IC's in the i.f. stages of its better line of FM

receivers and tuners. And the latest entrant in the field is Westinghouse Electric

Corp., with an IC portable phonograph. The new phonograph uses a conventional record

changer, but the familiar amplifier has been replaced by an IC measuring only 0.112"

x 0.085" and equivalent, performance-wise, to 39 components, consisting of transistors

diodes, and resistors.

But the IC news is not limited to the domestic front. Two major Japanese manufacturers,

Sony Corp. and Matsushita Electronics Corp., are producing radio receivers using

IC's, and another firm, Victor Co. of Japan Ltd., is selling a 25-inch color TV

set with a hybrid IC in its sound channel.

The Military, too, is going for IC's in a big way, not only in communications

and computer applications but, more recently, in the production of IC proximity

fuses. A World War II development, the proximity fuse is a miniature transceiver

used in artillery shells and bombs. In operation the device senses its approach

to a target by measuring the Doppler shift between shell and target. At a preset

distance, its detector circuit, activated by a reflected radio signal, detonates

the warhead charge.

Another recent development in the field permits smaller firms to design custom

IC's for their own products without the high investment cost of a complete manufacturing

facility. A sort of "do-it-yourself" IC kit the new item is an open-cased monolithic

silicon chip measuring only 0.086" x 0.124" but containing 60 components. The user

interconnects the various elements as needed to assemble his own custom circuit.

Produced by Westinghouse Electric Corp., the IC kit has been dubbed the "Insta-Circuit"

and is available in both flat-pack and TO-5 configurations. Suitable for manufacturers

schools and laboratories, the Insta-Circuit is definitely not a hobbyist item, since

the special microscope-equipped wire bonder required to make the final circuit connections

costs almost as much as a small car. The circuit chips themselves sell for less

than $40 each in unit quantities and less than $30 each in quantities of 50 to 400.

Reader's Circuit. Agreed that simple AM broadcast-band receiver

circuits are literally "a dime a dozen," the circuit in Fig. 1, which was submitted

by reader Doug Zimmer (14332 35th N.E., Seattle, Wash.), combines a number of interesting

features that make it suitable for demonstration or test purposes.

Doug has employed a standard tapped antenna coil, with the tap serving as a means

of matching the antenna. In addition, he has used a Darlington pair amplifier (Q1

and Q2) and a dual d.c. supply, permitting the selection of either a chemical battery

(B1) or a sun-powered battery (PC1) as the power source.

Radio-frequency signals picked up by the antenna are selected by tuned circuit

L1-C1 and detected by diode D1. Switch S1 provides optimum match for both long and

short antennas, insuring the best compromise between selectivity and sensitivity.

The detected audio signal is amplified by Q1 and Q2 and applied to an earphone plugged

into output jack J1. Capacitor C2 serves to bypass the r.f. signal.

Switches S1 and S2 are s.p.d.t. toggle, slide, or rotary types. Coil L1 is a

tapped loopstick antenna coil (Superex VLT-240 or similar) and C1 is a standard

365-pF variable capacitor. A tubular paper capacitor or ceramic unit can be used

for C2; working voltage is not critical. Diode D1 is a general-purpose type similar

to a 1N34A and Q1 and Q2 are low-power pnp types (typically, CK722, 2N107, or SK3003).

An open-circuit phone jack is used for J1.

Either a penlight cell or standard flashlight cell will be suitable for B1; PC1

is an International Rectifier type SIM silicon solar cell. Doug recommends moderate

impedance (500- to 5000-ohm) magnetic earphones. And you can use either a printed

circuit or point-to-point wiring when building this receiver.

Manufacturer's Circuit. An interesting experimental phase shifter

circuit is shown in Fig 2. One of the 20-plus practical circuits described in a

four-page folder recently published by Siliconix, Inc. (1140 W. Evelyn Ave., Sunnyvale,

Calif.), the phase shifter permits a continuous adjustment of the relative phase

difference between its input and output signals. It can be used for test purposes

or to demonstrate the concept of phase shift. It is particularly valuable for demonstrating

the changes in standard Lissajous figures as a signal's phase angle is varied.

The phase shifter consists of two cascaded split-load amplifier stages with appropriate

signal-combining phase-shifting networks between the drain and source output points.

Each stage provides from 0°·to 180° phase shift. Resistor R1 serves as Q1's gate

return resistor and as the input load. Resistors R2 and R5 act as drain loads while

R3 and R6 serve as individual source loads. Combinations C1-R4 and C2-R7 form, respectively,

the first-and second-stage signal-combining network, with the degree of phase shift

determined by their adjustable resistive elements (R4 and R7). Operating power is

furnished by a 12-volt battery, B1, controlled by s.p.s.t. switch S1.

Standard components are used in the instrument. Transistors Q1 and Q2 are FET

2N2609's. All resistors are half-watters; R4 and R7 are ganged potentiometers. Capacitors

C1 and C2 are high-quality ceramic or plastic film types. Switch S1 can be a toggle,

slide, or rotary switch, as preferred. A variety of 12-volt battery power packs

can be used for B1 including two 6-volt portable A types in series, or eight series-connected

penlight or flashlight cells. You can also power the phase shifter with a line-operated

d.c. power supply if you wish.

Observe good wiring practices when assembling the device, and keep all signal

leads short and direct. The "Phase Shifter" can be wired on a suitable etched circuit

board or on a perforated phenolic board, and housed in a small metal utility box.

A sine-wave audio signal generator can be used as the prime signal source for checking

phase shifts.

Transitips. Although possessing extremely - high input impedance,

insulated-gate field-effect transistors (IGT's, IGFET's, MOST's, or MOSFET's) can

be damaged quite easily by stray electrostatic charges. To protect these devices

against such damage during storage and shipment, semiconductor manufacturers use

techniques like wrapping the transistors in foil, twisting or soldering the lead

tips together, or shorting the leads by means of a metal eyelet. However, none of

these techniques provides adequate protection when the transistor is prepared for

installation in a circuit since the leads must then be separated.

A recently published NASA "Tech Brief" describes a simple and inexpensive device

(Fig. 3) for preventing accidental damage when MOSFET's are actually installed

in a circuit. If you do work with these transistors, you may want to use a similar

device. It is made from short pieces of 0.033-inch diameter music wire and 0.007

-inch diameter nickel wire.

First, bend the music wire to form a spring with small end loops. Then, form

the nickel wire into a single loop and attach its outer ends to the spring loops

by twisting and soldering. The spring is compressed during this operation so that

the nickel wire is held under tension.

Squeeze the spring, expanding the nickel wire loop, and slip the loop over the

transistor leads until it touches the case. Then release the spring, tightening

the nickel wire loop and shorting the transistor leads together. You can now remove

the manufacturer's protection feature (slip off the eyelet, untwist the leads, etc.).

Finally, an insulated Transpad is slipped over the transistor's leads and pushed

up against the taut wire loop to serve as a retaining disc.

The protected transistor can now be inserted in its socket and mounted on a circuit

board, or soldered in position. Once the transistor is installed, the protective

device can be removed either by compressing the spring (opening the nickel wire

loop) or clipping the fine nickel wire. And another thing: use a soldering iron

- not a gun - when wiring MOSFET's, and be sure to ground the tip of the iron to

the substrate lead before soldering the gate lead in place.

Until next month ...

Lou

Posted December 16, 2022

(updated

from original post on 9/5/2012)

|

By Lou Garner, Semiconductor Editor

By Lou Garner, Semiconductor Editor