|

March 1968 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Did I ever bore you with

my experience building a crossover network for a set of medium power speakers

(about 100 watts each) when in the USAF? Too bad I didn't have this "How to Build a Crossover Network"

article from a 1968 issue of Radio-Electronics magazine handy. I'll

spare you the details, but the era was 1979, and I was in tech school at Keesler

AFB studying to be an Air Traffic

Control Radar Repairman. Being amped up (pun intended) with electronics

theory with both semiconductor and vacuum tube circuits, I was looking to cobble

together a nice amplifier and a set of speakers. Back in the day, it was

possible to buy the components and build your own devices for often less than

buying a commercial equivalent. There was an electronics parts store right

outside the base gates in Keesler, Mississippi, so I found a schematic and

building article in an electronics magazine (Popular Electronics, I

think) and set about procuring components. I did not know enough about impedance

matching and frequency crossover networks then to design anything respectable

for the woofer, midrange, and tweeters I bought at Radio Shack, in the Gulfport

mall. I built the speaker enclosures in the base woodshop, using pine boards and

speaker cloth for the front also bought from Radio Shack.

How to Build a Crossover Network - Use a nomograph and skip

the math

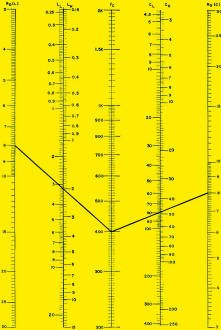

Crossover Network Nomograph

By Max H. Applebaum

An old adage states: "A chain is only as strong as its weakest link."

Similarly, the frequency bandpass of an audio system is only as wide as its narrowest

component.

Your amplifier and speakers may separately have flat responses beyond 20 kHz,

but if the wrong frequencies, in the wrong proportions, are fed to either woofer

or tweeter, decreased bandwidth and or distortion may be the result. If the speakers

are driven to full power ratings at frequencies outside their normal range, their

voice coils may overheat. If too much low-frequency energy is fed to the high-frequency

speaker, and some high-frequency energy fed to the low-frequency speaker, the overall

efficiency of the unit will be reduced substantially.

Obviously, a properly designed and built crossover network is not only desirable,

it is necessary.

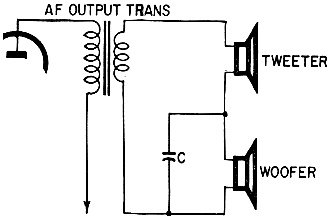

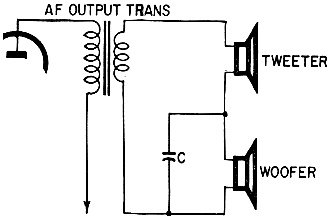

Fig. 1 - Simple crossover circuit uses a single capacitor

to keep the highs out of the woofer; Slope is approximately 6 dB/octave ... just

a bit too gentle for best high-fidelity work.

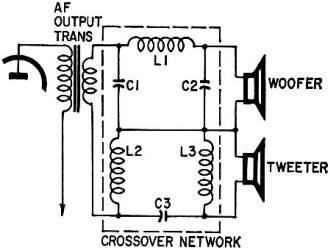

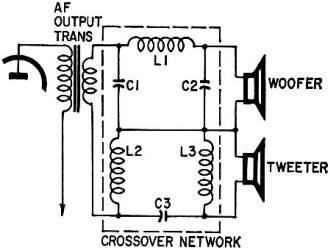

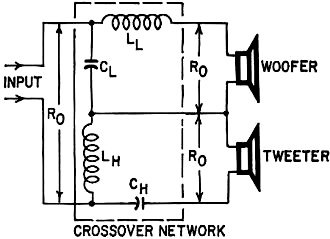

Fig. 2 - Double-pi network usually has a cutoff rate of about

18 dB/octave. This may be too steep for some applications because of excessive phase

shift above and below the crossover frequency.

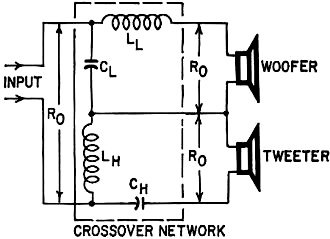

Fig. 3 - The 12 dB/octave crossover network shown here is

a happy medium between circuits that do too little, and those that do too much,

Phase shift two octaves above and below the crossover frequency is about midway

between the 180° for 18 dB/octave and 90° for 6 dB/octave networks.

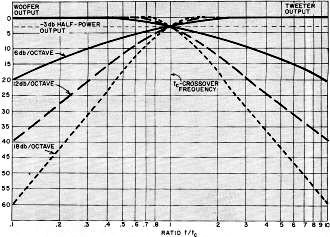

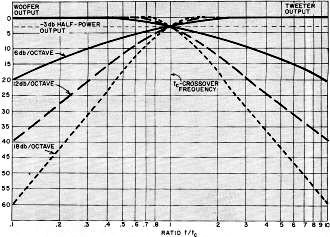

Fig. 4 - Crossover curves showing 6, 12, and 18 dB/octave

rate of cutoff. The crossover frequency is the frequency of the tone both speakers

reproduce equally.

Circuit Function

Crossover networks are built in many different configurations. The simplest type

a single capacitor shunting the woofer in a series-connected woofer-and-tweeter

pair (Fig. 1). A more complex type consists of two separate pi-section filters,

one high-pass, the other low-pass (Fig. 2).

When crossover networks are used, each speaker is supplied with a certain range

of frequencies, in varying degrees of amplitude. Typical crossover plots are shown

in Fig. 3; the curves represent relative attenuation versus the ratio of the actual

frequency to the cutoff frequency, for various rates of attenuation. Curves are

drawn for both the woofer and tweeter outputs at each rate of attenuation which

results from crossover networks normally used.

Crossover frequency (fc) is defined as that frequency at which the

power delivered to both speakers is equal. This usually occurs with a 3-dB attenuation

in power at each speaker, assuming an ideal network having no loss. The rate of

attenuation is given in dB per octave, where an octave is defined as that range

in which the frequency is either doubled or halved.

The simple capacitor circuit of Fig, 1 provides attenuation with a gradual slope

or rate of attenuation of 6 dB per octave. On the other hand, the complex network

of Fig. 2 provides a sharp slope of 18 dB per octave. Each has a certain disadvantage.

The single capacitor may not remove enough of the high frequencies from the woofer,

while the sharp slope of the complex network may cause too much phase shift.

One of the most popular networks is shown in Fig. 4-a "constant-resistance,"

series-connected crossover. This is a widely used arrangement, giving good fidelity

and providing an attenuation of 12 dB per octave, which strikes a happy medium.

While no calculations are required to use the accompanying nomograph, the following

formulas are presented to give you an opportunity to double check your work. Component

values are computed with the aid of equations taken from m-derived filter equations,

where m = 0.6 (m-derived filter design permits either impedance or the attenuation

characteristic to be predetermined ... a factor of 0.6 favors impedance match for

a little more than about 80% of the audio band of frequencies, hence the reason

for this particular network's "constant-resistance" characteristic) . The low-pass

network (feeding the woofer) consists of series inductor LL and shunt

capacitor CL. The high-pass network (feeding the tweeter) consists of

series. capacitor CH and shunt inductor LH. The equations

are:

IMAGE HERE

where fc is the crossover frequency and Ro is the nominal

speaker impedance (assumed to be a pure resistance and equal for both speakers)

and the output impedance of the amplifier.

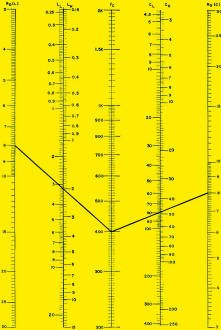

The solutions to these equations are rapidly found in the nomogram by merely

drawing two lines.

(1) From the value of fc, located on its scale, draw a straight line

to the value of Ro on the outer left-hand scale. The values of LH

and LL are found where the line intersects their scales.

(2) CH and CL are similarly found by extending a line from

the same point on the fc scale to the same value of Ro, this

time on the outer right-hand scale.

Note that the left-hand Ro scale is labeled R(L). This is used for

the solution of the inductance values. Similarly, the right-hand Ro scale

is labeled R(C). This is for the solution of capacitance values.

In the example shown, Ro = 8 ohms, fc = 400 Hz, CH

= 50 μF, CL = 80 μF, LL = 3.1 mH and LH =

2 mH. R-E

|