|

October 1969 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

It is hard to imagine anyone

who has not heard of the Dolby noise reduction process, even if he/she has no idea

what it is. Dr. Ray Dolby

developed his process in 1965, although it was not patented until 1969 - the year

this article appeared in Radio-Electronics magazine. At the time, "Dolbyized"

audio systems were not available in the consumer marketplace because the price was

prohibitively high - $1,495* for a basic A301 system. Only about 25 units per

month were being produced, primarily for recording studios and reproduction factories.

Dolby's magic that can reduce noise by 15 dB works on the

companding (portmanteau of

compression and expansion) principle, thereby eliminating or greatly suppressing

the discernable "hiss." Dolby B is still the most common version in use after

nearly half a century.

* $1,495 in 1969 is the equivalent of $12,928 in 2025 money per the BLS

Inflation Calculator.

Other Dolby articles from vintage electronics magazines include: "The Dolby System - How it

Works" (October 1969 Radio-Electronics), "All About Dolby" (June 1971

Radio-Electronics), "The

Dolby Technique for Reducing Noise" (August 1972 Popular Electronics),

"The

Dolby Noise-Reduction System" (May 1969 Electronics World).

The Dolby System - How it Works

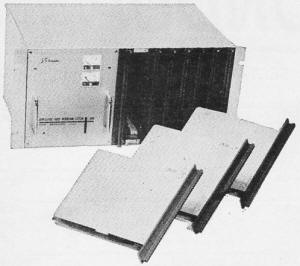

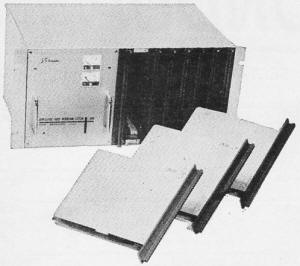

Rack-mounted A301 uses 4 plug-in PC cards for bands in identical

stereo channels.

Taking the hiss from hi-fi tape recording.

by Walter G. Salm

Rapidly gaining acceptance by major recording companies, the Dolby system cuts

tape hiss 10-15 dB and reduces print - through 10 dB. Although you need

a 'black box' to hear a Dolbyized tape, prerecorded tapes are sounding better than

ever.

There's an ever-present annoyance with tape recordings. It's called tape noise.

It takes various forms, with hiss being the most readily apparent to the listener.

The other noises are tape recorder rumble and scrape, and that ever-present gremlin,

print-through.

These noises occur at the tape recorder as the recording is being made-or in

the case of print-through, after the tape is made. The noise isn't present in the

signal coming to the tape equipment from the mixing console; up to that point, the

signal's nice and clean.

Various methods have been tried to eliminate noise, hiss in particular - exotic

filtering systems, compression or expansion amplifiers, and a variety of related

devices. Manufacturers frequently announce a "totally new" noise-reduction system.

Most of these systems work up to a point, but many inject "swishing" noises into

the recording because of the compressor amplifier's relatively slow attack time.

It can't react fast enough to the rapidly changing audio dynamics of the input.

Low-Passage Noise

A tape deck using one Dolby frequency band to cut tape hiss is

manufactured by KLH.

Where are these tape noises most noticeable? You don't need a cram course in

audio to know - it's always in the low-level music passages. In the loud sections

of a recording, there are plenty of desirable decibels to mask any intruding noise,

but hit that pianissimo section and suddenly the hiss comes storming through, along

with print, scrape and rumble. If the intrusive noise could be drastically reduced

in these low passages, so the reasoning goes, then the overall noise level would

be reduced.

Working on this premise, Dr. Ray Dolby developed his A301 noise-reduction system,

and started manufacturing it in England a couple of years ago. This system is inserted

in the signal path between the console and the tape equipment during the taping

session. During playback, the tape's signal must pass through the A301 again on

its way to the amplifier. A Dolbyized tape cannot be played back without the benefit

of reprocessing by the A301.

The A301 itself is actually a dual unit - two systems for two-channel stereo.

The same stereo unit that's used for recording can be used for playback, simply

by changing the connectors and flipping switches. The basic A301 is tagged at $1495,

so it's not a toy that the casual home recording enthusiast can buy for his amusement.

Tape-to-tape dubs do not require further Dolbyized (as long as tape-to-tape equalization

remains the same).

The overall effect is to reduce hiss and other noise factors by 10 to 15 dB!

A listening test demonstrates its effectiveness graphically. A-B comparison with

and without the A301 in the system makes one thing immediately apparent - with the

Dolby, there's absolutely no discernible hiss, not one little bit of it.

As a starting point, the Dolby system divides the audio spectrum into four frequency

bands: 0-80 Hz, 80-3000 Hz, 3-9 kHz and 9 kHz to the upper limit

of the audio spectrum. Crossover transitions between these bands are exceptionally

smooth, with no measurable discontinuities or attenuation.

Fig. 1 - System's feed-back loops provide necessary expansion

and compression to override background noise.

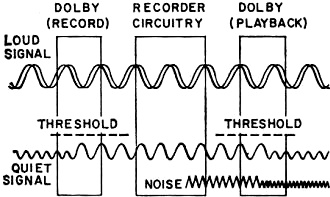

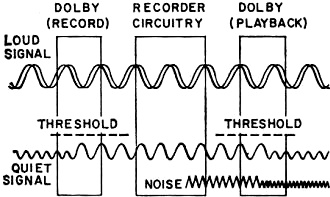

In the process of making a recording, low-level signals are boosted before reaching

the tape recorder and compressed by an identical amount in playback. The expansion/compression

moves the low-level signal up at least 10 dB. This 100 dB edge over intrusive

noise is maintained during expansion. The net result is that noise level is at least

10 dB lower than without the Dolby process.

In his description to the Audio Engineering Society in 1967, Dolby characterized

the basic elements of his black box as shown in Fig. 1. G1 and G2

are identical signal multipliers controlled by the signal's amplitude, frequency

and dynamic properties. During recording, network G1 passes low-level

signals to the adder, which adds a component (signal expansion) to the signal on

its way to the recorder. During playback, G2 p passes low-level components

to the subtractor, which partially cancels these noise elements in the signal. G2

also partially cancels low-level (desirable) signal components, thus offsetting

(compressing) the signal that had been partially expanded through G1's

action.

Mathematically, Dolby explains that if the input to the recording processor is

x (some function of time), the signal in the channel is y, and the output signal

from the reproducing processor is z, the condition is described as:

y = [1 + G1 (x)] x

(1)

and

z = y - zG2(z) or

z = { 1/[1 + G2(z)] }y

(2)

Combining equations (1) and (2):

z = { [1 + G1(x)] / [1 + G2(z)] }x.

(3)

Solving these equations, G1 = G2 and z = x. These solutions

show that the output signal will equal the input signal if G1 and G2

are the same, provided G(z) does not become -1 (no oscillation) and the functions

in (1) and (2) are continuous and single-valued - in other words, no tracking ambiguity.

It looks fine on paper, and the proof of the math is in the listening: it works.

In fact, it works so well that, in A-B tests, the listener can't help but wonder

if someone hasn't jacked up the hiss level in the unprocessed tape - the difference

is that marked and apparent. But no, there's been no monkeying with the tape - just

the normal amount of dubbing and processing.

Recording Companies "Dolbyize"

Identical A301 halves can serve for stereo or a record-playback

monitor.

A301 boosts low-level audio before recording, compressing it

in playback.

First to recognize the value of this new system have been the major recording

companies. Since every recording-tape and disc - must first go through several generations

of tape dubs, eliminating the noise that creeps into these transfers and mixes makes

the final, non-Dolbyized product that much cleaner.

True, the prerecorded tape purchased by the consumer has its own hiss and other

noises, but all the preceding noise in the production chain has been eliminated.

Thus, instead of a noise level as high as 10 to 14 dB, the finished product

may have a noise level of only 3 dB - a more-than-tolerable level. Tapes commercially

produced this way sound so good, in fact, that duplicators such as Ampex have started

touting their remarkably noise-free quality. Although discs have had very low noise

levels for some years, those pressed from Dolbyized master tapes sound notably quieter

and cleaner.

But it's no simple matter for a recording company to Dolbyize. First, there's

the very limited production of A301's. Ray Dolby has a baker's dozen technicians

in his London shop lovingly hand-crafting his A301's with a Rolls-Royce kind of

zeal and perfectionism. Total production capacity now is about 25 units per month,

and a large recording company may require at least that many units to handle its

manifold operations.

Dolby won't be hurried. He's a perfectionist, and he sees this perfectionism

as part of his stock in trade. A brilliant designer, he was largely responsible

for the development of the electronic circuitry for the original Ampex video tape

recorders while he was still a teenage undergraduate at Stanford University. He

received a PhD in physics from Cambridge in 1961.

Dolby at Popular Prices

The price picture isn't all that gloomy. There's one way the home recording enthusiast

can get his feet wet with the Dolby system. It's called the KLH recorder. This is

KLH's first entry in the tape field, and it's a lulu. In addition to a host of professional-caliber

specs, the deck has a built-in Dolby system - and all for $600. [A recently introduced

KLH Dolby tape deck sells for less than half this price.]

Actually, it's not a full-blown Dolby. The machine just uses the third frequency

band since this is where most hiss occurs, The KLH Dolby produces tapes recorded

at 3-3/4 ips with no higher noise level than tapes recorded at 15 ips without Dolby

treatment.

The KLH Dolby does a dandy job of killing hiss, and could be a very worthwhile

investment for the serious recording hobbyist who wants to maintain the best possible

quality in his home recordings. But what happens when he wants to dub and maintain

noise free tapes? Buy two KLH recorders? This might be what the Cambridge whiz-kids

had in mind, especially since they have an exclusive license to use the Dolby circuit

for manufacturing in the US.

The System's Noncompatibility

The Dolby system isn't a panacea. It can't clean up already recorded tapes. Its

function is to process the sound going onto the tape, and then to reprocess it as

it leaves the tape. It just won't clean up noise already indelibly etched in those

oxide particles.

Another problem: in today's ever-expanding tape channel capabilities, the A301's

price and relative unavailability makes it impossible to use with the 8- and 16-channel

audio mastering that is becoming more and more popular. This might involve having

as many as 16 units in a single recording studio control room for making just one

master tape. Fortunately, such multitrack originals are mostly used for "Acid" rock

and other popular sounds which don't make very critical demands so far as recorded

noise levels are concerned. It's in the realm of the serious recording - which is

usually taped in old-fashioned, two-channel stereo - that the Dolby system can really

come into its own.

Another problematical restriction: Dolbyized tapes simply can't be played back

on an ordinary tape system. The A301 must be in there to expand in the right places.

Without it, the dynamics and recorded sound in general will come out sounding pretty

weird. But in this era of electronic music and all of its strangeness to our more

conventional ears, this may well open the door to a new avenue of experimentation

with electronically generated musical effects. The engineer (or musician?) may play

with a console that controls the amount of Dolby expansion to be imposed on a Dolbyized

tape master.

And what about that A301? It's just a black box with some connectors on it. No

knobs to twiddle; no meters to watch: no circuit failures to keep the service techs

out of mischief. It's downright maddening! No knobs; really, Dr. Dolby!

|