|

December 1960 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

I was born (1958) in

the era of screw-in glass fuses in

household electric service panels (and ungrounded receptacles). There was always

a supply of replacements in the cabinet above the stove. Sometime around 1978,

prior to enlisting in the USAF, I replaced the fuse panel with a Square D

circuit breaker panel - a skill learned through four years of electrical work.

In the Air Force, I worked on a 1950s era air traffic control radar system which

consisted of many chassis assemblies having fuse holders on their front panels.

The racks themselves had a circuit breaker panel, but it was a retrofit from

sometime in the early 1970s. That was my introduction into the wide variety of

cylindrical glass fuses - high and low voltage, normal-, slow- and fast-blow,

time delay, etc. I learned of the reason why circuit designers employed each

type, and always used exact replacements when possible. Later, as a circuit and

systems design engineer myself, I always was careful to specify the most

appropriate fuse type. This 1960 article in Radio-Electronics magazine

is a good primer on fuse handling. Of no consequence, but I'll point it out

anyway, is that the

table of contents

erroneously lists this article as "Watch That Tube Replacement."

Watch That Fuse Replacement - The fuse that fits isn't always

the right one!

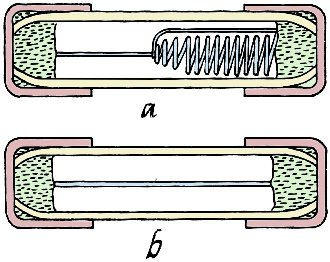

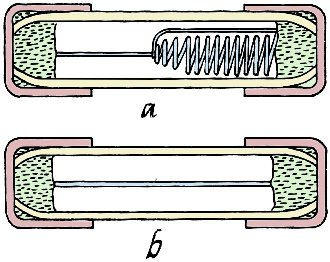

An anti-vbration fuse (a) and a standard type (b).

By James W. Essex

The mushrooming growth of electrical apparatus has helped the lowly fuse rival

the vacuum tube in abundance and variety. There are sizes and shapes to fit any

application - from circuits requiring slow-blow types for electric motors to vibration-proof

fuses (see diagram) for aircraft and mobile equipment. All come in a wide variety

of amperage ratings from the 1/500-amp 8AG fuse designed to protect sensitive instruments

to the 9AG with its 50-amp rating for Diesel trucks. All serve the needs of industry

(and the home). What would our costly circuits be worth (even home TV's) if a malfunction

of one part could destroy many others? Fortunately, with the aid of the fuse, we

can buy protection for a few pennies.

But there are limitations. Failing to note a few important facts about fuses

can negate their usefulness and practically eliminate their money-saving potential.

The electric windshield wipers on a friend's car failed one winter day. He tried

to get things going again by inserting another fuse. He didn't bother to observe

the markings on the one he took out. The one he put in was chosen merely because

"it fitted." It blew. Angry, he wrapped cigarette foil around it and tried again.

That fixed it. Everything was fine until a severe snowstorm caused the wipers to

bind momentarily. He had no protection. The electric motor burned out. Cost - $4.75

plus labor. Choosing the correct fuse in the first place would have been less costly.

Moral: do not chose a fuse replacement by size alone.

In our plant, we make fire engines, and fuses play an important part in the intricate

lighting network of a truck. Where time is sometimes short, choosing the wrong fuse

can be a serious mistake. Our wiring networks feed flashing lights, signal warning

lights, compartment lights for night operation, and panel lights.

Three of the fuses (to give only one example) are the same physical size but

have amperage ratings of 5, 20 and 30. Think what could happen if a 5-amp fuse were

inserted in a 30-amp circuit or vice versa because someone chose a fuse by size

alone. In one case, the circuit would not stand up. In the other, there would be

no protection.

Auto manufacturers have made every effort to guard against over- or under-fusing

by adopting a system in which fuse lengths correspond to amperage ratings. The shorter

the fuse, the lower the amperage-carrying capacity. The longer the fuse, the greater

the current capacity. But they have been victims of progress, just as the changing

designs in automobiles keep new cars old. According to Mr. A. M. Kalata of Littelfuse

Inc. of Des Plaines, Ill., it is an inheritance of the past which progress has outdated.

He says, "When the fuse industry first went into the manufacturing of fuses, they

were primarily for the automotive trade. The Society of Automotive Engineers started

a particular new line with the thought in mind that each amperage would have a different

physical length. But the line got too big. Consequently, they reverted to the commercial

standard field or nomenclature, as we know it." To name a few, there are 1AG, 3AG,

4AG, etc. The old SFE line (which is still the prefix for the automotive fuses)

is still with us. For example, you'll still find SFE 20 and SFE 14 fuses widely

used in autos to protect car radios. Others, like the SFE 6 and SFE 9, are used

for headlight circuits.

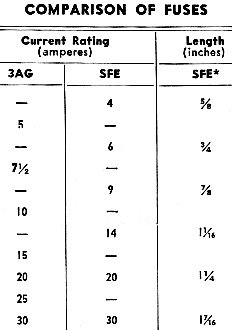

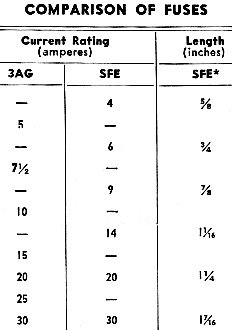

*All 3AG fuses are 1/4 inch in diameter and 1 1/4, inches long

How do the newer fuses - 1AG, 3AG, etc. - differ from the old? First, the SFE

line maintains the standard that fuse length corresponds to amperage. The new fuses,

like the 1AG and 3AG, have a standard length for each type regardless of amperage.

Thus, you can get a 3AG fuse which is 1 1/4 inches long in any amperage from 5 to

30, while only the 20-amp SFE has the same length. If you want a 30-amp fuse in

the SFE series, length would jump to 1 7/16 inches.

The variety of fuses in the one-length type continue on into the 4AG, 5AG and

on through 9AG types. Each group has its own particular use. Each group has a particular

length.

When replacing a fuse, note the nomenclature stamped on the barrel and put in

a similar one. Don't use a fuse just because it fits. For a rough guide in choosing

fuses for original equipment follow these steps:

Determine the physical dimensions of the fuse to be used. Then choose a fuse

that has the current-carrying capacity the circuit calls for, If you are working

with a circuit in which momentary surges occur but you don't want to sacrifice protection

by going higher in fusing, choose a slow-blow fuse, which has a high time lag, It

can withstand heavy surges yet blow quickly on shorts.

I've often seen technicians confused by the voltage ratings marked on some fuses-32

volts or 250 volts, for example. This simply means that the 32-volt fuse can be

used in any circuit up to 32 volts. Or a 250-volt fuse can be used in any circuit

up to 250 volts. If your application calls for 32 volts and the fuse you get is

marked with the propel' amperage, but 250 volts, it will work satisfactorily, but

it may cost a little more.

A listing of two series of 32-volt fuses. Note that the 3AG types are all 1/4

inch in diameter and 1 1/4 inches long. The length of SFE automotive fuses changes

in relation to current rating , making it impossible to put too large a fuse in

a circuit.

Posted May 7, 2024

|