|

December 1967 Radio-Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Electronics,

published 1930-1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

Vintage rotary dial phone.

Here is the second part

of a series of articles about stepping switches appearing in 1967 issues of

Radio-Electronics magazine. A standard (at the time)

dial rotary phone was

used as a familiar example in the

part one.

It delivers a single pulse for each number / letter set from 1, 2 (ABC), 3

(DEF), through 9 (WXY), 0 (Operator). On some phones, you can hear the clacking

of the switch contacts as the spring-loaded dial rotates from the selected

number back to home position. The stepping action as the result of dialing

occurs at the telephone system switching and call routing equipment at central

locations. There, stepping switches increment with each pulse received, and when

the full number of pulse sets have arrived, the circuit is complete and the call

put through to ring the phone of the intended handset. It is like a tumbler lock

that requires all the pins to be located in a unique position to permit the

cylinder to rotate and release the lock. This installment covers applications

like counting, selecting, routing, and sequencing.

Rotary Stepping Switches - They're Everywhere

The Roto-Netic stepping motor from Heinemann Electric Co. converts pulses into

rotary motion consisting of 10 precise steps. The device (see photo) consists of

a linear solenoid, a spring-loaded, plunger-type armature, and a ratchet-and-pawl

actuator on the end of the plunger that turns the output shaft.

When the solenoid is energized by a pulse, the plunger is drawn into the coil

against spring tension. After the pulse, the solenoid is de-energized, and the spring

forces the plunger back to "rest" position. This drives the actuator against a 10-tooth

star-wheel and produces 36° of shaft rotation (one step).

The actuator prevents the starwheel from rotating more than 36°, and a pawl

prevents reverse rotation. This means there's no possibility of overshoot, and overshoot

compensation isn't necessary. Each step is precisely the same as the last, and since

the power stroke occurs upon deenergization, even the last stroke is recorded in

case of power failure.

Speed is nominally 600 steps per minute and operates on either 12 volts dc or

115 volts ac with a bridge rectifier.

By Tom Jaski

Part 2 - Use them for counting, circuit selection and remote control

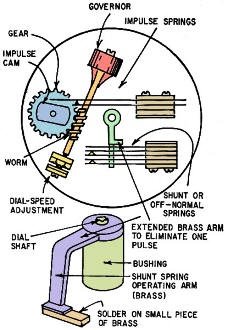

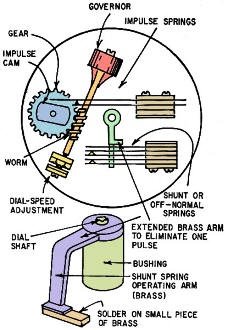

Fig. 1 - How a telephone dial's shunt-spring operating arm is

modified to eliminate the extra pulse that it normally generates.

Part I of this series described how rotary switches are used for the selection

of as many points as the selecting switch carried, but with only a single sequence

of pulses. A telephone dial is a useful control device which produces a maximum

of 11 pulses. Thus supplying control pulses with such a dial might make it necessary

to dial several times until the correct total number of pulses were delivered. Note

too that most telephone-type dials will deliver one extra pulse. Thus if 3 is dialed,

4 pulses are actually delivered by an unmodified dial.

Fortunately, it's possible to prevent such action. An electrical modification

can be made, by inserting a slow-release relay in the circuit. The relay is then

picked up by the first pulse - the relay blocks all line pulses until it is picked

up. It's also possible to modify the dial mechanism mechanically.

Changing a Telephone Dial

Fig. 1 shows how to eliminate the extra pulse from a standard older-type telephone

dial. Note the "off-normal" contacts. These are operated by a small brass foot attached

to the shaft. When the dial is rotated, the normally closed contacts are opened

(and the normally open contacts are closed). The pulses are produced by the interrupter

as the dial is on the return stroke. By extending the brass foot of the off-normal

contacts a little (this can be done by soldering on a small piece of brass) and

sending the pulses through one of these contacts, the extra pulse can be eliminated.

The last pulse is then blocked by the off-normal contact.

Fig. 2 - A two-level selector can select anyone of 99 points

by actuating S1, then S2.

Note too that the dial's mode of forming pulses - making or breaking contacts

- can be changed by adjusting the position of the interrupter cam on the geared

shaft.

Using the dial for selection leads to a more sophisticated, two-level system.

By using a switch of 10 points per level and 10 levels (Automatic Electric type

80, or equivalent), a 2-digit code can select anyone of 99 points. Fig. 2 shows

the diagram for such a selector system. S1 is a minor switch, operated by the first

digit dialed; this action selects the level of S2. The next set of pulses then rotates

S2 to the desired contact. As arranged here, the pulse line also becomes the control

line, and the circuit resets on a single pulse, but only after it has come to rest.

1CR is the relay which translates the pulses so a local power supply can be used.

As pulses arrive, motor magnet MM1 steps S1 to the desired level of S2. Slow-release

relay 2CR also energizes on the first pulse and remains energized until the pulses

stop. When they do, and 2CR releases, relay 3CR is energized through now closed

off-normal contacts ONS1 (which are on switch S1) and locks up on the supply. This

action removes future pulses from S1 and also sends pulses through contacts 1CR-3

to motor magnet MM2. This second set of pulses causes MM2 to rotate S2.

Fig. 3 - How stepper generates pulses. a- Negative (zero-voltage)

pulse output when arm is between contacts. b - Positive-pulse generator, c - Relay

1CR inverts pulses.

When this sequence is finished, 2CR again drops out, now connecting 4CR, through

2CR-3, to the line and also to the wipers that make the controlled circuit. A tone

arriving over this line does not affect the dc circuit, but a dc pulse will energize

4CR, a slow-release relay that will allow MM2 to step home on the interrupter and

will energize the release magnet of S1, resetting these switches. Off-normal contact

ONS1 on S1 then drops 3CR.

This circuit can deliver anyone of 99 points on demand (even 100 by including

the code 00). Using the same principles with more switches and relays would make

it possible to extend the system indefinitely. Most industrial control or monitoring

problems can be handled easily by a system that provides selection of any of 100

points - especially if the system has random access, like this one.

Output Pulse Polarity

One point about generating pulses with a stepper: The circuit of Fig. 3-a produces

negative pulses - i.e., no voltage during steps. Positive pulses - voltage only

during steps - can be produced with the hookups of Fig. 3-b and c. At (b) the outgoing

line is grounded as long as the switch remains on a contact; when the arm moves,

a positive voltage goes to the line. The resistor prevents shorting the battery.

At (c) a relay inverts the pulses.

The device of Fig. 4 has several functions. First, it counts pulses in decades

from a switch-type transducer. By mounting numbered discs or cylinders on the switch

shafts this count can be read directly. By supplying different tones for each switch,

characteristic signals can be sent out over a single line, to identify units, tens

and hundreds. (Of course, three separate lines can be brought out for this purpose.)

Circuit operation is simple: Incoming pulses operate relay 1CR, which is present

for the usual reason (to keep from loading the pulse line). It causes S1 to step,

and on the tenth pulse to S1 causes a wiper contact to connect MM2 to the positive

dc line. This starts S2 on its first step. This same wiper contact energizes relay

2CR, which resets S1. The next two steps operate similarly, and just one pushbutton

resets the whole circuit.

Again it's possible to say that this circuit can be expanded to include "thousands,"

"ten thousands" and so on. For practical purposes a count of 999 is quite large.

The circuit shown was used for registering gallons pumped by gas pumps in a service

station. A remote register totaled all the data from the pumps, using a storage

or "memory" circuit if several pumps were used simultaneously.

Fig. 4 - ( above) - Decade counting circuit. Separate lines send

units, tens and hundreds pulses to readouts. Distinctive tone codes can be sent

out over a single line.

Fig. 5 - Readout to indicate settings of switches in Fig. 4.

An extra relay on contact 30 can replace the reset (START) switch.

These circuits have been designed for direct-operated switches. For accurate

timing it may make a difference whether switches are operated direct or indirect.

An indirectly operated switch acts on the cessation of a pulse, rather than on the

starting of one. In the circuits shown, that makes little difference. Also, all

levels of contacts have been shown for nonbridging wipers. Bridging wipers running

across contacts would not generate pulses.

Another point: A switch steps home much faster than it steps out, and pulses

are produced by it much faster than dial pulses occur. (The latter run from 10 to

20 per second.) A switch stepping home on interrupters can be slowed down, as was

described in Part 1. But the homing speed of a minor switch can be regulated only

by adjusting mechanical friction or spring tension. The speed can be slowed down

some but not much.

Storing numbers

The circuit of Fig. 4 can be used to store three digits (and more by extension).

A simple readout can be built to show the final setting of the three switches. Such

a readout arrangement is shown in Fig. 5. The banks at right of the diagram are

one level each from the three minor switches of Fig. 4. The stepping switch used

for readout must be adjusted to make 30 contacts in sequence (on two levels), by

properly setting the wipers. Each set of 10 is connected to the minor-switch contact

banks. The switch will step through the first contacts (after starting, and this

switch steps slowly) and will energize 4CR when a "ground" is encountered on the

minor-switch bank. 4CR then stops further pulses (up to 10) from appearing on the

output line.

When point 10 is reached, 4CR is reset by 2CR-3, and the switch then scans the

bank of the second minor switch, and so on. The result is a series of three sets

of pulses which will signal in order the units, tens and hundreds count of the three

minor switches. If a pause is needed between sets of pulses, 2CR and 3CR can be

used also to energize slow-operating relay 5CR. For the duration of its on-off cycle,

5CR prevents 1CR from stepping the switch. This function is indicated by dotted

lines. The START button can be any momentary-contact type - even a relay contact.

For example, with several storage registers, a sensing circuit could be used

to hold off one register until another has been "read." Any relay can be used as

such a sensor by either the absence or presence of a voltage on its coil.

[In Fig. 5, the stepping switch is shown with two sets of 30 contacts arranged

in circles. Each set of 30 contacts has 3 wipers. The method of presentation is

used for simplicity. Actually, each set of 10 contacts is on a separate level and

the wipers are 120° apart. Thus, contacts 1 through 10 are on one level, 11

through 20 on the next, and so on. This switch - Automatic Electric type 44 or equivalent

- accommodates up to six 10-point bank levels. It is driven by a 33-tooth ratchet

providing 10 "on-the-bank" positions followed by an "off-the-bank" position for

each one-third revolution. -Editor]

Relay Code Selection

The individual code selector is a useful device. It can select one, and only

one of several circuits, by means of one line or radio channel. While such selectors

are made by various manufacturers (there are even electronics selectors with no

moving parts), it's possible to build this kind of selector by using stepping switches

and relays. Fig. 6 shows one circuit, which uses a type 44 switch, again arranged

for 30 points.

Incoming pulses operate the slow-release relay and the motor magnet (the usual

pulse relay has been left off). This switch, as shown has been arranged for the

code 4-5-9. (Up to 0-9-9 can be used with the 44 switch.) If the switch wiper lands

on any point connected to relay 2CR, the switch will immediately step home. Only

by successively landing on the code-specified contacts will the switch stay in the

last position it reaches.

For example, with the circuit shown, we can dial circuit 9 only by dialing first

4 and then 5. Any other sequence causes the stepping switch to home. 1CR-1 opens

at the beginning of the first series of pulses, disconnecting the battery from the

wiper and prevents false triggering. At the end of the pulse ICR-1 closes and connects

the battery to the wiper. If the correct number (4) had been dialed, 3CR is energized

and locked in through 3CR-2 and ONS2. The next series of 5 pulses steps the switch

to position 9.

If the code is misdialed or 9 is dialed directly, 2CR is energized and the stepping

switch homes through 2CR-1 and off-normal contacts ONS1.

For low digits an additional relay may be needed, to prevent landing on the third

digit position. It would be necessary to use a second code of pulses to ensure that

the switch comes to rest successively on all three points or not at all. Line connection

is made through a second level of contacts (not shown in the diagram). Any additional

pulse after the three-digit code will of course have the same effect as too many

pulses - it will send the switch home.

Where only a few selectors are to be used on a line, relay RY1 can be eliminated

simply by making the first digit 0 (tenth contact) and the second digit 9 or 0.

This makes it unlikely that accidental connection could take place, yet allows for

the use of 9 selectors. With that many pulses needed it is also unlikely that accidental

connection could take place, yet the circuit allows for the use of 9 selectors.

It is equally unlikely that random pulse noise might connect a selector.

The circuit of Fig. 6 has many applications. It can be used to read voltages

or currents of a remotely located transmitter (or any other electronic device, for

that matter). A suitable meter would be used at the dial (pulse-originating) location,

while series and shunt connections would be made at the stepper (pulse-receiving)

location.

Another use would be to switch microphone circuits remotely into a single amplifier

and line.

Rotary stepping switches have been used for many years in telephone, communications

and industrial electronics. Today's models are highly sophisticated and capable

of complex functions. In spite of the hundreds of thousands of steppers in daily

use, many persons interested in electronics have little knowledge of stepping-switch

function. These switches aren't really so complicated, however, as this series has

shown.

|