|

Super-low-noise-figure receivers

are absolutely essential in radio astronomy work. The need has driven major advances

in the state of the art of cryogenically cooled front ends with noise temperatures near absolute zero.

Antenna technology has also benefitted from radio astronomy due to the need for

precision steering and narrow beam widths. Phased arrays (aka interferometers) for

interstellar targets requires that element spacing be large enough to require separate

antennas as the elements, which creates a very large effective aperture, hence greater

angular resolution. Networks located continents apart are synchronized with the

use of atomic clocks to allow signal time of arrival and therefore phase to be accurately

measured. This story gives some of the early efforts.

Related articles: "How

We Listen to Stars and Satellites" - January 1958 Popular Electronics,

"Radio Astronomy

and the Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope" - February 1958 Radio & TV News,

"Radio Astronomy -

Low Noise Front-Ends" - June 1954 Radio & Television News, "Radar

Explores the Moon" - May 1961 Popular Electronics, "Cosmic Radio

Signals from Sun and Stars" - March 1948 Radio-Craft

Radio Astronomy

Fig. 1. One of the parabolic reflectors being used with

the interferometer now in operation at Cambridge, England (right).

By Dr. F. G. Smith

Astronomers are using new tools and techniques to provide the answers to some

age-old riddles of the universe.

In 1942 radar operators in England began to report a new kind of jamming observed

on their meter-wave-length receivers. Weak radar echoes became lost in the "grass"

on the (radar) screen, as if swamped by "noise" from a powerful transmitter. In

the Army Operational Group, a scientist named J. S. Hey - later to be known as one

of the pioneers of the new science of radio astronomy - examined the reports. He

established that the source of the "jamming" was no enemy station, but the sun,

and he noticed that at that time an exceptionally large sunspot was crossing the

sun's face.

Radio amateurs can detect this radiation from the sun during periods of sunspot

activity, and even television screens are affected by it, but few people know that

the sun and some other celestial objects are radiating short radio waves continuously.

The first observations of this steady radiation were made in 1932 by an American

radio engineer, Jansky, who was investigating the level of noise picked up by a

sensitive receiver on a frequency of 20 mc. He found that a directional antenna

gave a greater noise signal when pointing at the constellation of Sagittarius, in

the brightest part of the Milky Way, than in directions away from this high concentration

of stars. Ten years later, a radio amateur, Reber, built a parabolic reflector antenna

30 feet in diameter, in his own yard, and used this to make a map of received signal

strength on frequencies up to 500 mc. over a large part of the sky.

Fig. 2 - Array of full-wave dipoles at 3.7 meters.

This array is one-half of an interferometer for detecting radio stars. See text

for full details.

The 600-inch "radio telescope" installation at the Naval Research

Laboratory which is being used to study radio "signals" from the sun, moon, and

stars. Scientists use this research tool to extend man's knowledge of the universe

and to assist in forecasting the conditions for radio communications work.

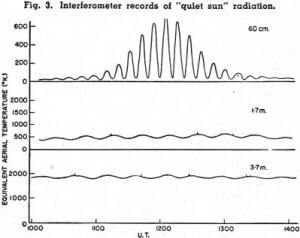

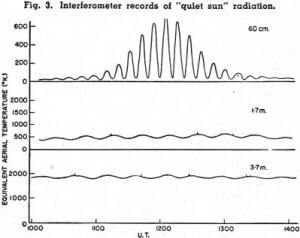

Fig. 3 - Interferometer records of "quiet sun" radiation.

Fig. 4 - Part of interferometer recording showing the presence

of several of the minor "radio stars."

Fig. 5 - Section of record with high sensitivity showing

intense source in Cassiopeia. See text for details.

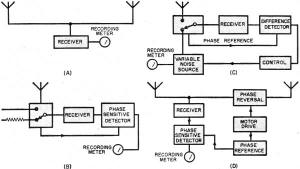

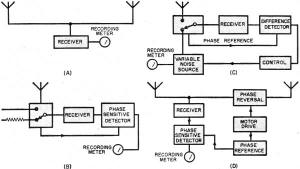

Fig. 6 - (A) How two similar antennas, spaced several wavelengths

apart, are used to detect radiation from the sun. (B) Use of a phase-sensitive detector

to eliminate receiver noise. (C) Improved version of the circuit shown in (B) in

which the antenna noise is continuously compared with the noise generated from a

controllable local source. a noise diode. (D) A pair of antennas connected in a

radio interferometer with a device for reversing phase of the signal from one antenna

periodically.

Fig. 7 - Parabolic reflectors used in an interferometer

for accurate direction finding.

Then came one of the most startling discoveries, again first hinted at by J. S.

Hey. Workers in Australia and England found that the radio waves picked up by Jansky

and Reber came, not only from the Milky Way but also from some quite definite points

in the sky, as though individual stars were transmitting to us. But there were no

bright stars at these points, and it was not until 1952 that these "radio stars"

were identified with visible objects in the sky; even then the objects were so faint

and inconspicuous that it needed the 200-inch Hale telescope at Mt. Palomar to find

them. Many astronomers have become interested in this new science as an extension

of astronomical techniques, and radio-astronomy is now being put to use in many

parts of the world extending our knowledge of the solar corona, interstellar gas,

nebulae, and even of our own ionosphere. In this article we shall be concerned less

with the results than with the methods, since the problems of technique are of great

interest and are not well known.

The two main problems facing the radio-astronomer wishing to study radio waves

from some object or region in the sky are simply stated. First, the power available

in his antenna is usually not greater than about 10-16 watt. Second,

the beam width of his antenna is usually vastly greater than the angular size of

the object, and the radiation picked up may well have come from many other objects

in this region. Both these difficulties, of signal strength and resolving power,

clearly call for large antenna systems and the radio astronomers are, in fact, building

large antennas for this work. In Manchester, England, there is now under construction

a very remarkable parabolic reflector antenna. This will be 250 feet in diameter,

and it will be so mounted that it can be directed towards any part of the sky. The

reflector will be made of wire mesh, and the accuracy of its surface will be such

that it can be used on wavelengths as short as a half meter or less. But many observations

can be made with much smaller antennas by using the principle of the radio interferometer.

If two similar antennas spaced several wavelengths apart and both directed towards

the sun, are connected to the same receiver, as in Fig. 6A, it is possible

to distinguish the radiation received from the sun against a background of radio

waves from the stars behind it, although this background may be several times more

intense than the solar radiation. The records of total power received from such

a radio interferometer as the sun moves slowly across the sky would be like those

in Fig. 3, showing some actual records on various wavelengths. In each the

sinusoidal variation of signal is due to the sun passing in and out of the interference

zones of the spaced antennas, whereas the steady signal, most evident on the longer

wavelengths, is from the extended source of the Milky Way background. An improved

method of recording recently used makes a record of only the sinusoidally varying

signal, giving the intensity of the solar radiation without any confusion from the

background radiation. The method of achieving this, known as phase-switching, will

be described after we have examined more closely the problem of detecting these

exceedingly small signals.

The character of the signals received from the sun and the stars is exactly the

same as that of "receiver noise." If we connect the input of a receiver first to

an antenna and then to a dummy load, the difference in signal may be demonstrated

as a change in the output of a detector circuit, but this change may be only a few

percent of the output, most of which is due to the receiver noise. It is necessary

to record this difference without including receiver noise, and this is achieved

in the schematic of Fig. 6B. The use of a phase-sensitive detector enables

a long time constant to be used in the output circuit, and the smoothed output records

the difference between the two levels of noise. An improvement is again made in

Fig. 6C, where the antenna noise is continuously compared with the noise generated

in a controllable local source, in practice, a noise diode. The output from the

local source is automatically adjusted to equality with the antenna noise, and a

record of the current in the diode gives a direct record of antenna noise unaffected

by the characteristics of the receiver. The records in Fig. 3 were made in

this way.

These methods of detecting small noise signals have been widely used in the measurement

of the total noise power received at an antenna. But in radio astronomy it is often

necessary to select only that part of the noise which is coming from a small source

in the sky, perhaps a radio star or a sunspot, and to disregard a large proportion

coming from a diffuse background of other sources. A new method of detection is

then used.

In the schematic of Fig. 6D a pair of antennas is connected in a radio interferometer

with a device for reversing the phase of the signal from one antenna periodically.

The lobes of the interferometer radiation pattern then shift by a half lobe width,

due to the phase shift, and the signal from a source smaller than the lobes of this

pattern will change periodically by an amount depending on its position in the pattern.

Again a phase-sensitive detector is used to measure this periodic change in output.

In Fig. 4 we see the recorded output of such a phase-switching receiver connected

to a large interferometer operating at a wavelength of 3.7 meters, shown in Fig.

2. The output is centered on zero, and the groups of oscillations each record the

passage of a radio star through the antenna receptivity pattern as the earth rotates.

This method of recording radio stars has been used in the accurate location of some

of the most intense radio stars. A record from the intense radio star in Cassiopeia

using part of the same interferometer is shown in Fig. 5.

The interferometer in Fig. 2 is located along an east-west line so that

each radio star is detected as it crosses the meridian, a line from the zenith to

the south point. The time of this crossing, found from the record, gives the position

of the star in the sky. The timing may often be carried out to an accuracy of about

0.1 second, but unfortunately the actual position of the star cannot be determined

quite as accurately as this. For one thing, the position of the interferometer axis

must be known, and with the antennas of Fig. 2 this cannot be defined to better

than about 2 minutes of arc. The interferometer in Fig. 7 was specially built

for such work, and the line joining the bearings of the two parabolic reflectors

was determined to 10 seconds of arc. These reflectors are two of the antennas of

the "Wurzburg" radar set much used by the Germans during the war. They are 27 feet

in diameter, and the two are mounted 900 feet apart, 200 wavelengths at 1.4 meters,

the wavelength used in the most accurate direction finding experiment yet made.

With this interferometer, a radio star in the constellation of Cassiopeia was located

within an area only 10 seconds by 30 seconds of arc. The position was given to astronomers

at Mt. Palomar, who found with the 200-inch telescope a new type of nebula exactly

in the right place.

This new branch of science is certainly providing new tools for the astronomer

in his survey of the heavens, but it may also prove to be a useful approach to some

studies of the ionosphere. When Hey first detected radiation from a radio star,

he distinguished it from the background because the signal was fluctuating in a

peculiar way. This effect we now know to be very similar to the scintillation, or

"twinkling," of ordinary stars. It is caused by refraction in irregularities in

the earth's ionosphere, through which the radio waves pass, and by studying the

fluctuations in signal it has been found that the irregularities are in the upper

part of the F-region, inaccessible to pulse-sounding methods. It appears that the

top of the F-region occasionally becomes corrugated, to an extent of about one percent

of its total depth, the wavelength of the corrugations being about 5 km. The whole

structure is drifting across the earth at a speed of several hundred miles-per-hour,

and the effect on the ground is similar to the moving pattern of sunlight on the

bottom of a swimming pool when waves disturb the surface. The cause of this ionospheric

disturbance is still unknown.

Another useful way of investigating the ionosphere has been suggested. As the

radio waves from a radio star pass through the ionosphere they may be refracted

in such a way as to make the star appear in the wrong position. The amount of this

displacement may be measured, and depends primarily on the total number of electrons

in a vertical column right through the ionosphere. Pulse-sounding methods are not

suitable for this measurement, and it is likely that understanding of the ionosphere,

still full of mysteries, will be helped by these new experiments.

The most exciting discoveries of radio astronomy have been in the search for

sources of radio waves in our galaxy and in extragalactic nebulae, and this search

is being pursued with great vigor in several places. The new Manchester antenna

will be used in this work. Recently some details were published on a new antenna1

at the Ohio State University designed to carryon the search. There is, however,

a large interferometer antenna now in operation at Cambridge, England, which may

well be called the largest radio-telescope in the world. Its parabolic reflectors

cover an area close to 50,000 square feet. Results from a survey of radio sources

in the Northern sky should be available in a few months' time. No description of

this instrument has yet been published, and a picture of one of the reflectors in

Fig. 1 is the only one available as yet. It is hoped that this instrument will

provide some further clues to the solutions of the great problems "What are radio

stars?"; "How many are there in our galaxy?"; "Do other galaxies have radio stars

like ours ?" - questions we may hope to have answered in only a few years from now.

Reference

1. Kraus , J. D. and Ksiazek, E.; "New Techniques in Radio Astronomy," Electronics,

September 1953

Posted September 10, 2019

(updated from original post on 7/7/2013)

|