|

December 13, 1965 Electronics

[Table of Contents] [Table of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Electronics,

published 1930 - 1988. All copyrights hereby acknowledged.

|

The December 1965 issue of

Electronics magazine reported in multiple articles on the state of Japan's

electronics industry (see the

table

of contents for other stories). Japan's indisputable lead today in many realms

of semiconductor, commercial, and consumer products proves successful implementation

of the strategy described in these articles. Per this piece's NTT employee authors,

"In one decade, Japan's semiconductor industry has become the world's second largest.

Pioneering engineers, a variety of unusual devices, and breakthroughs in miniaturization

techniques account for phenomenal growth." A notable claim is taking credit for

inventing the ceramic "pill" packaging format for high frequency transistors.

All these articles appeared in this issue:

Westernizing

Japan |

Japanese Technology - The New Push for Technical Leadership |

Japanese Technology - When You're Second, You Try Harder |

Japan Stresses Research |

Japan: An Industrious Competitor

Japanese Technology - When You're Second, You Try Harder

Nippon Electric Co.'s multiple diffused base transistor (left)

compared to a conventional planar transistor at right. By widening the base area

with a second diffusion, NEC reduces base spreading resistance, thus increasing

maximum frequency

In one decade, Japan's semiconductor industry has become the world's second largest.

Pioneering engineers, a variety of unusual devices, and breakthroughs in miniaturization

techniques account for phenomenal growth.

By Takuya Kojima and Makoto Watanabe,

Electrical Communications Laboratory, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corp.,

Tokyo

Large scale production of semiconductor devices is the nucleus of the Japanese

electronics industry. More than 400 million transistors were produced last year,

making Japan's semiconductor industry the second largest in the world, trailing

only the United States. Yet quantity is not the industry's sole accomplishment.

Japanese engineers have created some unusual devices such as the passivated mesa

transistor, a bidirectional twin transistor, the Esaki diode, and a double-diffused

pnp transistor of unique structure.

All this has happened in the last decade. The dominant force behind such rapid

growth has been Japan's pioneering - in the transistorizing of consumer products

such as a-m and f-m radios, tape recorders and television sets, now small enough

to be called micro sets.

The structure of the Japanese industry helped too. All the makers of semiconductor

devices in Japan - and the total number is less than 20 - also manufacture consumer

products, other electronic equipment or both. Because they are in the same company,

information flows rapidly between device builders and equipment designers.

Most of the semiconductors made in Japan are germanium devices, and go into consumer

products. New consumer products, however, require better quality devices. Thus,

the transistorization of large television reviewers, with screens up to 19 inches,

demands high-frequency transistors and high-power devices. Communication and industrial

equipment also needs special-purpose devices of high quality. Although silicon technology

is new in Japan, its spread has been rapid and most semiconductor suppliers produce

both germanium and silicon devices.

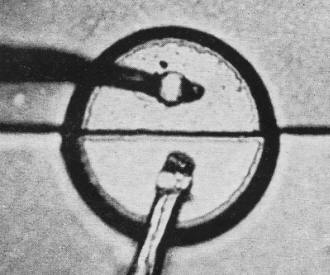

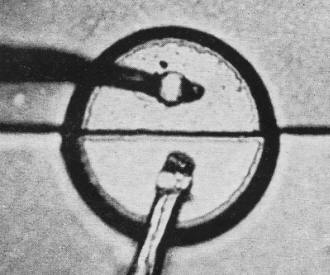

Emitter mesa transistor built by the Nippon Electric Co. (left)

withstands drive-in effect which had destroyed conventional mesa transistor (right).

Challenge of Higher Frequencies

As in the United States, there is great pressure in Japan to produce higher-frequency

devices. For example, television makers want transistors capable of operating up

to 1,000 megacycles for ultrahigh-frequency receivers. For this application, Japanese

suppliers offer both germanium and silicon devices.

To boost operating frequency, Japanese firms are trying either to minimize the

base spreading resistance of their devices or to minimize the collector capacitance.

The reasons become evident from the equation for maximum frequency of oscillation

of a transistor:

where rbb' is the base spreading resistance,

cc is the collector capacitance and τec is the carrier

transit time between emitter and collector. The base spreading resistance and collector

capacitance degrade performance. Base spreading resistance not only decreases the

power gain and output power but also degrades the noise figure. where rbb' is the base spreading resistance,

cc is the collector capacitance and τec is the carrier

transit time between emitter and collector. The base spreading resistance and collector

capacitance degrade performance. Base spreading resistance not only decreases the

power gain and output power but also degrades the noise figure.

To lower this resistance in silicon transistors, firms have introduced some novel

device structures. For example, the Nippon Electric Co., Japan's biggest microwave

equipment manufacturer, uses a multiple base diffusion process to add another area

of impurities in the 2SC288, 2SC289, and 2SC272 devices (shown above). After the

usual diffusion has formed a conventional base area, a second process diffuses impurities

just outside the emitter area, widening the base thickness and reducing the base

spreading resistance. The rbb'cc product of the 2SC288 is

only 3 picoseconds; the base resistance is less than 1/3 that of a conventional

transistor.

NEC also achieves a low base spreading resistance with a second approach called

emitter mesa structure and shown in the figure below. This structure reduces the

drive-in effect in which impurities in the base region are driven toward the collector

area, forming a small projection in the collector junction plane.

Though the effect is more pronounced in a silicon mesa transistor, where the

impurity is gallium, than in a planar transistor where the impurity is boron, It

becomes critical in any high-frequency transistor. That's because a high-frequency

device has an extremely narrow base width which is a bottleneck in the base region

between the area immediately beneath the emitter junction and the area outside the

junction. The bottleneck causes an appreciable increase in the base resistance and

disturbs the uniform carrier flow in the base area.

In the emitter mesa structure, a mesa formed by a vapor etching process prior

to diffusion, offsets the drive-in effect. The height of the mesa is just enough

to compensate for the depth of the projection that would be formed in the junction

plane by the drive-in phenomenon, Thus an ideal flat junction structure results.

There is one other advantage of the emitter

mesa structure: it eliminates unwanted parasitic capacitance and carrier injections

around the vertical outside edge of the base. Although these can be ignored in an

ordinary device, they are appreciable in a high-frequency transistor whose emitter

width is 5 microns or less. The parasitic capacitance decreases the high-frequency

amplification factor in the small-current region of the emitter; the excess carrier

injection at the edge decreases the current amplification factor in the large-current

region of the emitter. By using the emitter mesa structure NEC increases the gain

by 3 db throughout the range of emitter current and decreases noise by 0.5

db. There is one other advantage of the emitter

mesa structure: it eliminates unwanted parasitic capacitance and carrier injections

around the vertical outside edge of the base. Although these can be ignored in an

ordinary device, they are appreciable in a high-frequency transistor whose emitter

width is 5 microns or less. The parasitic capacitance decreases the high-frequency

amplification factor in the small-current region of the emitter; the excess carrier

injection at the edge decreases the current amplification factor in the large-current

region of the emitter. By using the emitter mesa structure NEC increases the gain

by 3 db throughout the range of emitter current and decreases noise by 0.5

db.

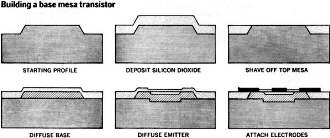

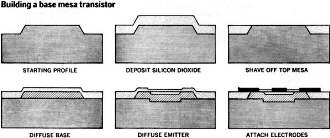

From the equation for the maximum frequency of oscillation of a transistor (above),

it is clear that frequency can also be increased if collector capacitance is reduced.

In the base mesa transistor designed by NEC, the geometry lowers this characteristic.

In the structure (p. 83), the base area is defined by a deposited layer of silicon

dioxide. Since only a small region of the base is needed to make contact with the

metallization of the electrode, the capacitance of the metallized portion to the

collector is negligible. Such low collector capacitance makes the device well-suited

for application in wideband-amplifiers - and especially in amplifiers with automatic

gain control because circuit capacitance changes less with changes in voltage stemming

from the gain control.

It seems clear that all three techniques - multiple diffused base, emitter mesa,

and base mesa - could be applied to one device, to produce even better transistors

capable of handling higher frequencies.

At the Matsushita Electronics Corp., the semiconductor producer of the big Matsushita

Industrial Electronics Co., another approach to reducing collector capacitance has

been taken with extended base planar transistors. A highly doped area just beneath

the extended base electrode shields the electrode from the collector. In the Matsushita

2SC562 series, the base-to-collector capacitance is as low as 0.15 picofarads.

Minimum base-to-collector capacitance eliminates several bothersome effects.

By definition, in an extended base electrode device, a metallized contact to the

base is extended along the silicon dioxide layer on top of the collector bulk semiconductor

region for easier bonding of the base lead wire. If the device has an extremely

small base area, the parasitic capacitance between the extended base electrode and

the collector bulk semiconductor region is comparable to the capacitance of the

intrinsic collector junction. Such a high capacitance makes it impossible either

to increase the power gain of the transistor in ultra-high-frequency ranges or to

stabilize transistor operation at lower frequencies where capacitance can cause

feedback. In addition, if the intermediate frequency stage of an amplifier is equipped

with automatic gain control, high capacitance causes the bandpass characteristics

to change with the gain of the transistor.

Most of the high-frequency devices Matsushita has developed are going into television

sets. The 2SC562 is used in the control stage of television i-f amplifiers with

forward gain control. The 2SC563 goes into the output stage of i-f amplifiers. And

the 2SC593, with a power gain of 20 db at 450 Mc and a cutoff frequency more than

1,500 Mc, is for uhf tuners.

Because silicon devices cost considerably more than germanium ones, there is

still a lot of interest in germanium devices in Japan, even for high-frequency applications.

Japanese engineers use mesa, planar and alloyed diffused types of germanium transistors

in high-frequency applications. One example is the 2SA448, a double-diffused pnp

transistor, shown on page 84, developed by the Sony Corp. The mesa surface is divided

into two steps of equal area, separated by a space of only one micron. One step

is the base contact metallization region; the other is the emitter contact metallization

region.

One micron or less separates the emitter electrode (top) and

base electrode (bottom) of Sony's double diffused germanium pnp transistor. Used

for high-frequency applications, it can be fabricated easily.

Even though high precision is required in manufacturing, the fabrication of the

2SA448 is relatively simple. First, a coating of silicon dioxide is deposited uniformly

over the entire face of a germanium wafer. Then gallium is deposited on the oxide

coating and diffused through it to form the emitter layer of p+ material. Trenches

in the SiO2 are formed by a photolithographic process. The p+ material

below these trenches is etched out to form deeps whose bottoms reach to the p-material.

Then the SiO2 layer is removed, leaving a surface of alternating p+ and

p- stripes. At this point, the device is a p- wafer with parallel ribbons of p+

material along its upper surface.

In the next step, the base diffusion of n-type material takes place. A layer

of n-type material forms at the base of the trenches and under the p+ ribbons because

the diffusion constant of the n impurity is 1,000 times that of gallium which was

the p+ impurity. But, because the quantity of n impurity is much smaller than that

of gallium, the p+ region stays a p+ region. Aided by geometry, the n impurity extends

further into the p- region at the bottom of the trenches than under the p+ region.

Since the n layer under the p+ layer is the base region of the finished device and

the n layer at the bottom of the deeps is the base lead attachment region, the finished

transistor has a thin base and low base spreading resistance.

After the second diffusion, a shadow evaporation process forms the aluminum base

and emitter contact regions. In this process, the entire base and emitter contract

regions are metallized with only about a micron spacing between them. No precision

positioning is required since the step in the structure provides a built-in mask.

Finally, the wafers are diced and individual pellets mounted on tabs for mesa

masking and mesa etching. Mounting, lead attachment and sealing are conventional.

Built this way, Sony's 2SA448 has a power gain of 8 db at 1 gigacycle. Noise

figure at this frequency is 7 db in the common emitter connection.

Power Transistors

The considerable effort to produce high-frequency devices has not been duplicated

with high-power units. Though many companies make power transistors, both silicon

and germanium, most are conventionally designed.

How Sony's germanium transistor, 2SA448, performs at high frequency.

Its performance is good up to 1 gigacycle.

Epitaxial or triple-diffused silicon power transistors are manufactured with

capacities ranging from 10 to 150 watts - not exceptional when compared with devices

made in the United States with power ratings up to 300 watts. Currently the 2SD137

made by Kobe Kogyo has the highest collector breakdown voltage of any device made

in Japan: 300 volts. Recently, both Kobe Kogyo and Toshiba (Tokyo Shibaura Electric

Co.) started manufacturing overlay transistors which have higher power capability

in the high-frequency range.

In entertainment and industrial applications, alloy drift and diffused base germanium

transistors are still used almost exclusively. In audio-frequency amplifiers, horizontal

deflecting systems for tv picture tubes, and regulated power supplies, they have

proven to be free of secondary breakdown. Many people wonder whether silicon will

ever replace germanium for such applications.

The Passivated Mesa

Although the planar structure is clearly the most widely used for silicon transistors,

it has one serious limitation: the breakdown voltage of the collector is low. After

examining the probable causes of this limitation, Hitachi Ltd., has developed an

improved passivated mesa transistor which has a better collector junction.

In Japan, as in the United States, the causes of collector breakdown in planar

structure are not clear. Partially, it's caused by geometry: the electric field

is concentrated at the corners of the diffused area. Some researchers believe that

a large amount of impurities in the base region cause surface breakdown. The surface

of the base has a greater concentration of impurities than the region adjacent to

the horizontal collector junction because diffusion produces a graded layer with

a higher concentration of impurities near the surface.

At other times, a poor silicon-silicon dioxide interface seems the cause. Or,

if the silicon-silicon dioxide surfaces are. separated by an n+ surface layer, breakdown

can occur too.

Hitachi's new process produces a mesa structure that has a high collector breakdown

voltage, low noise figure, small leakage current, and a high current amplification

factor in the small current region.

The process is applied to a completed mesa transistor. After silicon dioxide

is deposited on the transistor by the thermal decomposition of organic oxysilane,

a thin film of lead is deposited onto the oxide layer. Finally, the device is exposed

to high temperature so the lead and silicon dioxide can combine to form a protective

glass whose composition is lead oxide and silicon dioxide.

Many kinds of transistors treated this way are available for entertainment and

industrial applications. For example, the Hitachi 2SD190 is a silicon device with

a BVcbo of 300 volts; the 2S280H is a twin transistor for low-level differential

amplifiers and it has an excellent reliability record.

Hitachi claims the process can be applied to other semiconductor devices, too.

Beginning of Field Effect Devices

Among Japanese engineers, the field effect transistor is still a novelty whose

application is very limited. Only five companies supply them at present: Toshiba,

Hitachi, Fujitsu, Kobe Kogyo and Mitsubishi. Typical of these devices is the Toshiba

2SJ13, a p-channel junction FET with a transconductance of 3.5 milliohms. The Mitsubishi

3SK15 series is a depletion mode metal oxide semiconductor device for general purpose

use. The Hitachi 3SK11 is a depletion mode n-channel MOS fabricated by a technique

called field cooling process.

Depletion mode, enhancement mode and even nonuniform channel MOS devices can

be made by the field cooling process. A small quantity of movable impurities, such

as sodium ions, are impregnated in the silicon dioxide layer. An electric field

applied between the gate and bulk crystal at high temperature causes the impurities

to drift through the oxide layer, changing the surface potential of the silicon

appreciably. When the surface channel has reached the desired conductance, the field

is removed and the device is cooled, fixing the impurities in the oxide layer.

Making the Esaki Diode

Unquestionably the best known Japanese semiconductor development is the Esaki

or tunnel diode, invented by Leo Esaki at the Sony Corp. in 1957. After a resounding

acceptance, particularly because of its apparent high speed, the tunnel diode turned

into a big disappointment. One reason was the incorrect use of the device in circuits.

It is a diode and cannot replace transistors or other multi-lead devices. But another

reason was reliability. Initially, every manufacturer fabricated Esaki diodes by

a conventional alloy-etching process. It produced a diode whose structure resembled

a boulder balanced on a point, and the device was not very rugged.

In addition, performance requirements were in conflict with each other. For a

high cutoff frequency, the junction diameter has to be about 5 microns or less;

but for high reliability, the final junction diameter cannot be smaller than the

initial junction diameter before etching. It turned out that a 5-micron diameter

area - needed for high-frequency cutoff - was too small for lead attachment.

Because the Esaki diode was a truly Japanese development, Japanese companies

continue to work with it. To build more reliable devices, some of them have switched

to a mask technique. At Sony, where the device was developed, a process called the

bridge technique was developed, using a combination of evaporated mask and etching

methods.

Low-drift differential amplifier uses two pairs of twin passivated

mesa transistors. Voltage gain is 40 db; drift is 10 microvolts per degree centigrade.

In the output stage of a home radio. a high voltage passivated

mesa transistor is protected by a silicon varistor.

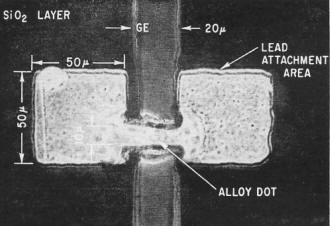

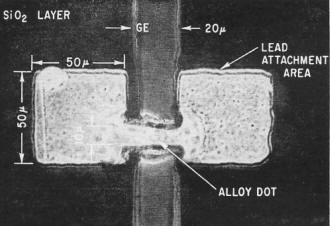

In Sony's new method of fabricating tunnel diodes, a dot of alloy

material bridges the trench between two metallized areas. The result is a more rugged

device.

Applications of Passivated Mesa Transistors

In the new Sony process, after a germanium slice has been coated with silicon

dioxide, a trench about 20 microns wide is cut in the oxide coating by photolithographic

etching. Then two regions, 50 microns by 50 microns, on each side of the trench

are metallized. An alloy dot bridges the two metallized areas over the trench, forming

a junction at the bottom of the trench and ohmic contacts to the two metallized

regions. A final etching process brings the diode to the desired characteristics

of peak current and peak-to-valley current ratio.

In a diode made this way, the etched junction is only slightly smaller than the

original junction. But the junction does not have to contribute to mechanical support;

rather, the ohmic contact region supports the junction.

Besides being stronger, the new diode has better electrical characteristics.

One which Sony produces has a cutoff frequency of 10 to 21 gigacycles, self resonant

frequency of 14 to 22 gigacycles, and a capacitance-to-peak current ratio of 0.1

to 0.25 picofarads per milliampere.

Other High-Frequency Diodes

Because of Japan's interest in and use of solid state microwave, there has been

a lot of activity in developing high-frequency diodes for communication systems.

Among the first Japanese semiconductor developments was the Kita diode or silver-bonded

diode developed at the Electrical Communications Laboratory of NTT, and now manufactured

by Nippon Electric Co.

The Kita diode has outstanding characteristics when used as a parametric amplifier,

upconverter or frequency multiplier at microwave frequencies. The reason is the

small capacitance of the depletion layer, typically less than 0.5 picofarads, and

a low series resistance, less than 10 ohms. Although the device was first developed

in 1954, its greatest applications have appeared in the past two or three years.

Now new ones are being discovered in high-speed switching, clamping and clipping.

Making the diode is relatively easy; the big difference is in the method of bonding.

In a conventional diode gold wires are used. In the Kita device, the tip of a silver

whisker, containing a small amount of gallium, contacts a bulk crystal which has

been highly doped with n type germanium or silicon. Applying a large current pulse

produces a very small area of p+ material on the crystal, completing the fabrication

of the diode.

As an indication of Japanese activity producing a variety of diodes:

• Nippon Electric Co. produces high frequency Zener diodes with low junction

capacitance.

• Fujitsu Ltd., the Nippon Electric Co., and the Mitsubishi Electric Corp.

make silicon diffused varactors for solid state microwave systems of 2, 4 and 6

Gc. The Mitsubishi MVE6006 can deliver an output of 3 watts at 4 Gc when used as

a frequency tripler. That's the highest output at this frequency of any Japanese

diode.

• The New Japan Radio Co., Ltd., Fujitsu Ltd., and the Sanyo Electric Co.

make variable-capacitance diodes with a retrograded junction, a device which is

also called a hyper-abrupt junction diode. These devices are used as a tuning element

which covers a wide frequency range and as a modulator in f-m communications systems.

• Fujitsu Ltd., has also developed a new gallium-arsenide light emitting

diode that throws a narrow beam of non coherent light through a transparent window

at the top of the mounting. It has been used in a micromanipulator which accurately

positions tools driven by a pulse motor.

Special Purpose Devices

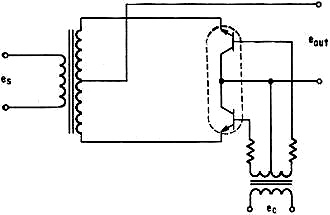

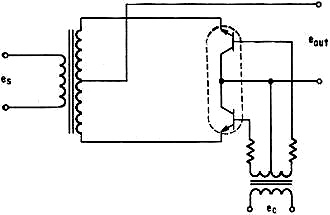

Balanced modulator has a symmetrical twin transistor (in color)

built by the Nippon Electric Co. This configuration has high conversion efficiency

and small carrier leakage because the saturation resistance and voltage are appreciably

smaller than those of diodes used in conventional modulators.

A look at some of the special purpose devices developed in Japan helps understand

both the spread of Japan's semiconductor industry and its electronics industry.

One unusual device is the V-203, a bidirectional twin transistor, built by the

Nippon Electric Co. for balanced modulators. A unique junction structure and a controlled

epitaxial technique produces symmetrical characteristics (see circuit below).

Another device is a high-speed four-layer diode developed by Mitsubishi. A two-terminal

silicon device, it has a break-over voltage of only 3 volts and a switching time

of 20 nanoseconds. Most probably application is in fast digital circuits.

And still another new device is the gate-turnoff silicon controlled rectifier

produced by Toshiba. Labeled the M8392, it has a turnoff gain of 8; that is, a gate

current of 500 milliamps can turn off a current of 4 amps.

Power Handling Devices

Although both power equipment manufacturers and transistor makers make power

handling devices - silicon rectifiers, silicon controlled rectifiers, and silicon

symmetrical switches (bidirectional four-layer diodes) - the development effort

doesn't begin to compare with that in the United States. In general, SCR's, for

example, are expensive and are not yet used widely. Until recently, Japanese SCR's

did not have the large current-carrying capacities of those available in the U.

S. and Europe.

The situation is changing and some new devices supply the strongest evidence.

A new SCR developed by Nippon Electric Co. uses a silicon slice 1% inches in diameter;

it's the biggest SCR developed in Japan. Called the V-179, it has a mean forward

current of 700 amps, repetitive peak reverse voltage of 2,350 volts, and a surge

current rating of 9,000 amps.

One not so large is the CJ-021 built by Hitachi for ac-dc conversion in a 2,200

kilowatt electric locomotive. Ratings of this SCR are: a peak reverse voltage of

1,200 volts and a mean forward current of 390 amps. Because so much of Japan's extensive

railroads net is electrified, there is likely to be an increased use of SCR's

for conversion and speed control as the manufacturing volume increases and decreases

the cost.

Hitachi has one other interesting SCR, the CR-93VE, a small high speed device.

It takes only 3 microseconds to turn on 1,000 amps, and 6 microseconds to turn off

10 amps. But it can handle 1,000 amps only for short surges.

Silicon symmetrical switches are a specialty of the Shindengen Electric Manufacturing

Co. which makes several series of them. Its KXB series contains two terminal bidirectional

switches with breakover voltages of 100 to 200 volts. The K17B-10 and K17B-20 have

a rating of 150 amps, bidirectional rms current and the K5B can handle 12 amps.

Another supplier is Hitachi, whose FR-01 is a 5-layer switch with one control

gate electrode. A control current, either positive or negative, of 100 milliamps

can fire the switch in either direction, regulating an rms current of 16 amperes.

High-Voltage Rectifiers

Still a small part of the Japanese semiconductor industry is the manufacture

of high-voltage rectifiers, capable of handling reverse voltages of 3,000 and 4,000

volts. The Hitachi HO3-DA has a peak reverse voltage of 3,000 volts and a rated

mean forward current of 470 amps. A device made by the Sanken Electric Co. has a

breakdown voltage exceeding 4,000 volts; mean forward current is 150 milliamps and

the forward voltage drop is only one volt when maximum forward current flows.

A Neat Packaging Idea

At the Nippon Electric Co., miniature high-frequency

transistors are assembled on rolls of Kovar material to simplify manufacturing and

handling. The transistors are mounted in tiny ceramic headers called Micro Disks

which also minimize parasitic capacitances and inductance created by conventional

single-ended packages. At the Nippon Electric Co., miniature high-frequency

transistors are assembled on rolls of Kovar material to simplify manufacturing and

handling. The transistors are mounted in tiny ceramic headers called Micro Disks

which also minimize parasitic capacitances and inductance created by conventional

single-ended packages.

Assembly is simple and automated. Leads are stamped from a continuous flat strip

of Kovar. Silicon dies are mounted on the collector leads and interval leads are

attached between the base and emitter and the leads on the strip. Tiny ceramic disks,

recessed like an ashtray in the center are coated with low-melting glass, then attached

from both sides of the strip. When the assembly is heated, the glass melts and a

hermetic seal is formed. The leads are cut out from the strip and the devices separated

from each other for final testing.

Shindengen makes an avalanche rectifier diode, the S5Z-50, with a reverse surge

power rating of 2.5 kilowatts for 10 microsecond pulses. In the S5Z series, peak

reverse voltages range from 400 to 1,200 volts; mean forward current is about 20

amps.

Any survey of the Japanese semiconductor industry would not be complete without

mentioning several processing techniques which have been developed.

Many of the high voltage devices made in Japan receive a special surface treatment

called ONV, which means oxidation by nitrogen dioxide vapor. The treatment, developed

at the Electrical Communications Laboratory, consists of two processes: cleaning

the silicon surface in an atmosphere of hydrogen fluoride and nitrogen dioxide;

and oxidizing at a low temperature. Such treatment raises breakdown voltage, minimizes

leakage current and steps up the surge power rating.

Though germanium devices far outnumber silicon devices produced by Japanese semiconductor

makers, more research effort is being applied to silicon technology because it is

newer. For example, the Oki Electric Co. has perfected a simple process for depositing

polycrystal silicon.

The company has made a tiny diode with an upper ohmic contact formed by depositing

polycrystal silicon. The polycrystal material is deposited in a window cut into

oxide masking. During fabrication, it acts as an impurity source for diffusing the

p-n junction beneath it, and afterwards as a protective coating and contact to the

completed junction. This technique supplies a rigid, reliable contact that is simple;

no ball or fancy contact structure is required as it is with many kinds of silicon

diodes.

Another application of silicon polycrystal produces isolated silicon islands

in integrated circuits in a process similar to Motorola's EPIC process - but simpler.

In Motorola's process, a silicon crystal is etched to a waffle-like pattern and

then oxidized. Polycrystal is deposited over the waffle-like face; the bulk of the

single crystal material is removed by grinding and lapping until the waffle-like

projections are a group of oxide-isolated islands supported by polycrystal silicon.

In the Oki process, the starting material is a two-layer structure of thin silicon

single crystal on a polycrystal bulk. In the etch that produces the waffle-like

structure, the single crystal is cut down to the supporting polycrystal. The structure

is then oxidized and polycrystal silicon deposited just as it is in the EPIC process.

But the original poly crystal silicon is removed, leaving a group of oxide-insulated

islands supported by polycrystal silicon. What makes this process simpler is that

the polycrystal material is removed easily.

The Authors

After receiving his Ph.D. from Osaka University, Takuya Kojima (left) started

his engineering career by developing tubes for wideband amplifiers. He switched

to semiconductor devices in 1955 and now heads solid state engineering work at the

Electrical Communications Laboratory.

Ever since he graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1953, Makoto Watanabe

(right) has had an interest in semiconductors. As a staff engineer at the Electrical

Communications Laboratory, he develops high frequency germanium and silicon devices.

Posted October 23, 2023

(updated from original

post on 8/24/2018)

|

where rbb' is the base spreading resistance,

cc is the collector capacitance and τec is the carrier

transit time between emitter and collector. The base spreading resistance and collector

capacitance degrade performance. Base spreading resistance not only decreases the

power gain and output power but also degrades the noise figure.

where rbb' is the base spreading resistance,

cc is the collector capacitance and τec is the carrier

transit time between emitter and collector. The base spreading resistance and collector

capacitance degrade performance. Base spreading resistance not only decreases the

power gain and output power but also degrades the noise figure.