|

June 1931 Radio-Craft

[Table

of Contents] [Table

of Contents]

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics.

See articles from Radio-Craft,

published 1929 - 1953. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

This reactance measuring bridge

circuit which appeared in a 1931 issue of Radio-Craft magazine employs

a very unique element for generating an alternating current: an electromechanical

buzzer which doubles as an audio source. Sure, it doesn't produce a pure sinewave,

but for the method used here to determine inductance and capacitance it does not

matter. Rather than attempting to measure an absolute value of inductance or capacitance,

a known reactance is used as part of a balanced bridge. This is by no means a precision

instrument since accuracy depends on the user's interpretation of the presence or

absence of an audible "buzz" in a pair of headphones, but in an era when "real"

test equipment was beyond the budgets of many (maybe most) hobbyists, the scheme

was better than nothing at all. This reminds me a bit of the "Bumble Buzzer" continuity

checker we used at the Westinghouse Oceanic Division in the 1980s for "buzzing out"

multiconductor cables; it was in a black and yellow plastic project enclosure and

emitted an audible buzz when the measured resistance was below a certain value. See also

National Radio

Institute advertisement, December 1954 Radio News;

Mathematics in Radio in July 1932 Radio News;

Measuring Inductance and Capacity, June 1931 Radio-Craft;

Mathematics in Radio,

March 1933 Radio News;

Radio Frequencies and Their Allocation, June | July 1940 National Radio News;

Your Radio Training and the Defense Program, December 1940 | January 1941

National Radio News.

Measuring Inductance and Capacity

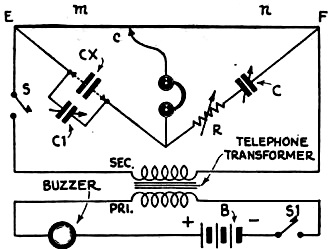

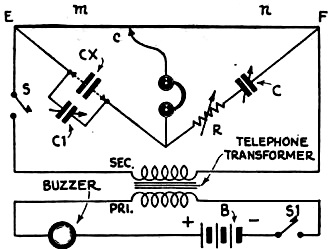

Fig. 1 - The simple bridge, with buzzer and phones, for

measurement of inductance.

How the Experimenter May Utilize a Reactance Bridge

By James A. Dowie*

In the February issue of Radio-Craft appeared a description of the construction

of a Wheatstone bridge which could be used to measure unknown resistances, such

as are used in radio work. ("A Home-Made Slide-Wire Bridge,"

by A. W, Bonser, page 482). The object of this article is to show how the

Wheatstone bridge may be used also to good advantage by radio-tricians and Service

Men for making various measurements of inductance and capacity - two important factors

necessary for satisfactory reception of radio signals. Inductances, as used in radio

work, function under alternating current; therefore, measurements should be carried

out with alternating current.

Fig. 1 shows the circuit arrangement used in this bridge. In series with

the battery "B," a buzzer is placed; and the combination is utilized to give an

alternating current through the various arms of the bridge. (A high-frequency buzzer

or a vacuum-tube A.F. oscillator, such as have been described in Radio-Craft, may

also be used for this purpose.) With this arrangement a pair of phones serves as

the indicating device; they are connected as shown in the diagram. If audio-frequency

current flows through the phones, a sound will be heard; while, if no alternating

current flows, no sound is heard. The Wheatstone bridge is then balanced by sliding

the contact c over the arms m, n of the bridge until a minimum of sound is heard;

this is the condition of balance.

(Note: "Minimum" sound is specified; because it may be impossible to obtain a

zero sound-balance with this apparatus, on account of induction and stray capacity

effects. Knowing this, we will now consider the case of measuring the inductance

of a coil by means of such an arrangement.).

Measurement of Inductance

In the circuit arrangement of this bridge used for inductance measurements, m

and n are the slide-arms of the bridge; c is the sliding contact; L the known inductance,

and X is an unknown coil whose inductance is to be measured.

This circuit is in theory the same as that used in the resistance measurement,

described in the preceding article; when the slider c is moved along m and n until

a balance is obtained, a minimum sound will he heard in the telephones. Then the

following relation is true:

Thus, if a single standard inductance L and a slide-wire bridge with phones,

battery and buzzer are available, the values of unknown inductances may be easily

measured.

This relationship is only true in practice when the unknown inductance X is of

the same order of magnitude as the standard inductance L. By this it is meant that

inaccuracies will arise in these measurements if the standard inductance is about

0.1 millihenry, for instance, while the unknown inductance is 10 millihenries; because

the ratio of m to n would then be too great to obtain an accurate balance. If the

ratio of m and n is about 1 or 2, then a sharp balance will be had.

The following notes should be of interest to radio-tricians interested in accurate

measurements with a bridge:

The formula given above for inductance is sufficiently accurate for all practical

purposes; however, it does not take into consideration the resistance of the inductance

coils. If there is a great discrepancy between the resistances of the two coils

L and X, it is quite possible that a sharp balance will not he obtained. Balancing

a Wheatstone bridge circuit is something like tuning a radio receiving circuit;

since resistance in a resonant radio circuit makes for extremely broad tuning.

Balancing a Wheatstone bridge is equivalent to reducing the resistance, and thus

enables sharp balance or tuning. If the resistances of the coils are not balanced,

a sharp balance will not be secured and, therefore, the accuracy of the measurement

will be destroyed; since the accuracy of the measurement in a Wheatstone bridge

depends upon the sharpness of the balance.

Correction for Resistance

Since all inductance coils have some resistance, a better arrangement of the

bridge is shown in Fig. 2, where each coil has its compensating resistance

(R3, R4) in series.

For precision measurements, it is necessary to strike a balance for both the

inductances and the resistances of the coils. The inductance balance is secured

by means of the buzzer and headphones; while the resistance balance is secured by

a voltmeter and the battery B2 for the source of supply. In this bridge, Fig. 2,

we use two double-pole double-throw switches (S1 and S2); one is used for switching

on either the voltmeter V or the phones PH for the balance indicator. (The potentials

of B1 and B2 must be found by experiment).

Fig. 2 - The bridge arrangement for balancing inductance

and resistance to obtain a true reading of the former.

Fig. 3 - Use of the bridge for capacity measurements, with

the necessary compensation for zero setting.

Fig. 4 - The circuit connections of a Wheatstone bridge

using a high-frequency buzzer, for accurate measurements of capacity.

Fig. 5 - The most satisfactory operation of the bridge is

obtained with an A.C. oscillator giving a good note.

Fig. 6 - A wooden base, 8 x 45 inches, will mount a one-meter

rule as shown; or the "reciprocal" scale of the February article may be used.

The buzzer and phones are used for the A.C. inductance balance, with switches

S1, S2 thrown left; the battery and voltmeter, for securing a D.C. resistance balance,

the switches thrown right. The variable resistors, R3, R4, placed in series with

each of the inductances enable us to balance the inductance arms for resistance.

The following gives the method used for operating this type of bridge circuit.

First, a balance is obtained for the A.C. signal; the double-pole, double-throw

switches are both thrown to the left, to use the buzzer and phones. The sliding

contact c on the wire m-n is varied until a balance is obtained. The switches are

then thrown to the right to place the battery and voltmeter in the circuit. With

the sliding contact c fixed at the position previously obtained, vary the resistance

of R3 and R4 until the voltmeter v indicates a balance, by zero deflection. Now

switch over again to the buzzer and phones, and vary the position of the sliding

contact until a balance is obtained, as indicated by a minimum sound in the phones.

Again switch back to battery and voltmeter, keeping the sliding contact c fixed

in the new position previously found; and very the resistors R3 and R4 until a balance

is obtained. Alternate this way until a very sharp balance is obtained on both D.C.

and A.C. - then note the values of m and n and apply the formula previously given.

It will be noted that the important adjustment of the sliding contact c was not

changed in balancing the resistances of R3 and R4; since the important adjustment

of the slider determines the inductance measurement. The above formula is absolutely

correct and is based upon both types of balance thus obtained.

Measurement of Capacity

The Wheatstone slide-wire bridge may be used also to measure unknown capacities,

there being required in this circuit but one known capacity. Fig. 3 illustrates

the connections for this bridge; in which C is the known capacity and CX the unknown

capacity, while m and n are the lengths of the two arms of the slide-wire, which

are adjusted for a balance by a minimum sound in the phones.

It is evident that, with this arrangement, the resistance in one arm of the bridge

is balanced against the impedance of the condenser in the adjacent arm. (The impedance

of a condenser is the resultant of resistance and reactance but, as the resistance

is so very low, compared to the reactance, it can be disregarded and the entire

impedance considered as reactance.)

The reactance of a condenser varies inversely as its capacity; while the reactance

of an inductance varies directly, and therefore the preceding formula must be rewritten

and used in the following form:

For example, the scale has 100 divisions and the sound is minimum in the phones

at a point on the wire 25 divisions from E (Fig. 6); leaving 75 divisions for

n, between F and c. Assuming that we use a standard capacity value of 0.002-mf.

for C, we may substitute these values, giving

In all these measurements using a buzzer to supply the alternating current to

the bridge, it is advisable to set the buzzer at some distance from the bridge,

or muffle it in some wav; for otherwise it will be difficult to determine whether

the sound is coming from the phones and due to the current passing through them,

or whether it is direct noise from the buzzer. (A "high-frequency" buzzer is more

quiet. See Fig. 4.)

An excellent source of A.C. voltage for measuring inductance and capacity is

a vacuum-tube audio-frequency oscillator which does not have the above-mentioned

fault of buzzers. The terminals of the oscillator are connected to the points E

arid F of the bridge. (See Fig. 5) Resistor R1 controls the amount of A.C.

fed to the bridge.

In these measurements, a calibrated variable (air dielectric) condenser may be

used as the standard C; with this, a very large range of unknown capacities may

be very simply measured.

First, the slider is set at the mid-point of the length of resistance wire, thus

making m equal to n. The variable condenser C is then adjusted until a balance is

obtained. Then, the dial reading of the standard condenser C will indicate the capacity

of the unknown condenser CX; since m and n are equal.

A midget condenser, C1, is necessary in this measurement so that a balance (at

the minimum capacity of C) may be had, and the zero reading of C taken without the

unknown condenser CX in the circuit. It is required also to bring the balance point

further up the scale on C when measuring small values of CX.

The effective resistance of the condensers enters into the measurement of capacities

exactly as in the measurement of inductances; but, in the case of condensers using

air as the dielectric, this is not very important because the resistance of such

condensers is almost zero. However, where condensers have different dielectrics,

(for instance, air, and "mud" compositions), there will be a considerable difference

in their resistances; which means that it will be impossible to get a silent point

in the telephones. However, a fair balance point can usually be secured.

Because of the insulating properties of condensers, the circuit will be open;

therefore, it is impossible to balance this bridge with direct current. However,

a good balance, with fair accuracy, is generally found when using the fundamental

circuit shown in Fig. 3.

In order ·to secure a more accurate balance with this bridge, it is necessary

to connect a variable resistor R in one or the other of the condenser arms, (X1

or X2, Fig. 3.); the proper place is found by trial. This will compensate for

any resistance effect introduced by the condenser in the other condenser arm. The

readings of this resistance, with and without the condenser CX, are indicative of

the losses in the condenser under test. This is a check-up of "leaky" condensers.

Construction of a Slide-Wire Bridge

The connections between the components of the bridge are made on the top of the

wooden base by means of brass straps 1-1/2 inches wide and 1/4-inch thick (Shown

in Fig. 6.). The holes for the terminals are tapped the correct size.

The wire used for m and n may be of any standard make of resistance wire (such

as nichrome, German silver, constantan, etc.) and its gauge from No. 24 to No. 28

B & S.; as these are the most convenient sizes with which to work. (Note: Be

careful to secure uniform wire, for the resistances of the two arms of the bridge

m and n are proportional to their lengths only if their cross sections are equal.)

The resistance wire is stretched taut almost flat on the board, and securely

fastened at E and F to the brass strap at each end of the bridge. The meter-scale

is mounted directly beneath the resistance wire, thus positioning the slide-wire

about 1/16-in. above the meter-scale. The contact slider c may be one of the sharp

edges of a 1/4-in. brass rod; the opposite edge being soldered to a length of rubber-covered

lamp cord. Compare Fig. 6 with Fig. 2.

* Chief Instructor, National Radio Institute

|