|

May 1972 Popular Electronics

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Hewlett Packard introduced their electronic

HP-35 Scientific Calculator in 1972. It was not the world's first

pocket-size electronic calculator - that distinction went to the

Busicom LE-120A. However it was the first to be designed for the

science, engineering, and financial communities with its many built-in math functions.

Use of Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) might have scared off many would-be

users who were easily confused by anything other than the traditional notation (algebraic)

that mimics written form; i.e., 2 + 3 = 5 (ALG), as opposed to 2 3 +

[=] 5 (RPN). Wisely, HP made both modes selectable. Reading through the

HP-35 manual makes it evident that this calculator was not for

the feint of heart as it presents concepts like memory stacks, imaginary numbers,

vectors, scientific notation, hyperbolic trigonometry, logarithms, permutations,

curve fitting, and more. Hewlett Packard introduced their electronic

HP-35 Scientific Calculator in 1972. It was not the world's first

pocket-size electronic calculator - that distinction went to the

Busicom LE-120A. However it was the first to be designed for the

science, engineering, and financial communities with its many built-in math functions.

Use of Reverse Polish Notation (RPN) might have scared off many would-be

users who were easily confused by anything other than the traditional notation (algebraic)

that mimics written form; i.e., 2 + 3 = 5 (ALG), as opposed to 2 3 +

[=] 5 (RPN). Wisely, HP made both modes selectable. Reading through the

HP-35 manual makes it evident that this calculator was not for

the feint of heart as it presents concepts like memory stacks, imaginary numbers,

vectors, scientific notation, hyperbolic trigonometry, logarithms, permutations,

curve fitting, and more.

In this installment of Mac's Service Shop, Mac and Barney discuss the newfangled

device that ushered in a new era in calculators. The introductory price in 1972

was $395 - that's equivalent to

$2,979 in 2024 money. Working

HP-35 calculators can be bought on eBay for as little as $50.

See also "Mac's Service Shop: Buying and Using a Pocket Calculator."

Mac's Service Shop: A Versatile Pocket Calculator

By John T. Frye, W9EGV, KHD4167 By John T. Frye, W9EGV, KHD4167

From back in the service department Mac heard the front door screen of the service

shop slam behind Matilda and Barney as they returned from their lunch hour. "I'm

glad I forget each winter how lovely the first really warm day of May can be," Matilda

was declaring. "It's wonderful and exciting to be able to discover this over and

over again each year."

"Yeah, it's not bad out there," Barney admitted gruffly as he pushed through

the swinging door of the service department. He found his employer seated at the

service bench staring down at the varicolored keyboard of a little object lying

on the bench in front of him. The object was flanked by a couple of open books and

a scratch pad.

"Hey, what are you doing?" Barney demanded.

"Checking out a graduation gift for my favorite nephew who finishes high school

next month - no, that's not quite true," he broke off. "Actually I'm having a ball

playing with this fascinating bunch of integrated circuits."

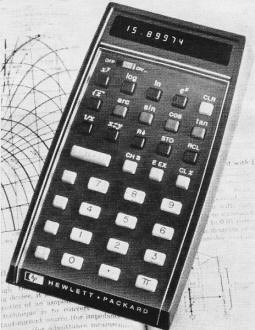

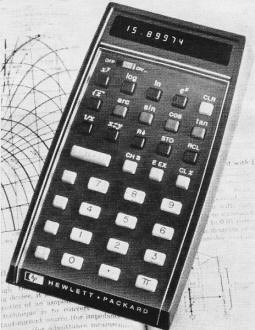

Hewlett Packard HP-35 electronic scientific pocket calculator

"What is it? Looks a lot like the minicalculator Matilda has out on her desk

except it has more keys."

"It's Hewlett-Packard's new HP-35 Pocket Calculator," Mac answered, "and you're

right about the number of keys. Matilda's has fifteen; this one has thirty-five.

You may have also noticed her calculator displays eight digits while this one displays

ten, but these are only superficial differences. There are other more important

ones."

"I've got the feeling I'm going to hear about them," Barney said resignedly,

heaving himself up on the bench. "But do you think the kid is going to appreciate

something to work math with just after getting out of school? I'll bet he'd rather

have a portable stereo or TV set."

"If he doesn't appreciate this thing now, he will when he starts to Purdue in

the fall and begins four years of studying electronic engineering," Mac promised.

"Believe me, this thing can be worth much more than its nine-ounce weight in gold

to an engineering student or to any other student seriously involved with math."

"Yeah?" Barney questioned skeptically.

"What can it do that Matilda's calculator can't?"

"The one Matilda has is known in the trade as a 'four-banger' because it performs

the four basic arithmetic functions: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and

division. However it does these with far greater accuracy and speed than is possible

with a slide rule and also keeps track of the decimal point. Used in connection

with a good set of logarithm and trig tables, it can sharpen the accuracy and shorten

the time of performing more complicated functions and would be of great help to

any college student.

"But now listen to what this little jewel, the Cadillac of the miniature calculators,

can do. In addition to the four arithmetic functions mentioned, it can also extract

the square root of a displayed number at the stroke of this key. Separate keys are

provided to yield almost instantly the trigonometric functions of sin x, cos x,

tan x, arc sin x, arc cos x, and arc tan x. Another key gives the common logarithm

of any displayed number, while still another key yields the natural logarithm. This

key marked x is used to find e to any power without having to punch in the value

of e. This one marked π allows you to punch that constant, correct to ten places,

into an equation with a single key stroke. This 1/x key gives you the reciprocal

of any displayed number, and this one (xy) is used to raise a displayed

number to any power within the range of the instrument - all this with an accuracy

of 10 significant digits."

"Whew!" Barney gasped. "You weren't just beating your gums when you said that

little gadget could do a lot of things. How big a number will it handle?"

"It has a dynamic range of two hundred decades from 10-99 to 1099.

It displays ten significant digits with the decimal point automatically positioned.

Answers larger than 10-2 and smaller than 1010 are automatically

displayed in floating point. Outside this range, numbers are expressed in scientific

notation, with the exponent of 10 shown in the extreme right. For example, the answer

to an equation yielding Boltzmann's Constant in joule /K°, which is 1.38 x 10-23

would display 1.38 on the left and -23 on the right."

"What does this key marked

do?" Barney asked. do?" Barney asked.

"That brings up another feature of the HP-35. It has a four-register stack plus

one storage memory. Let me see if I can explain: suppose we want to multiply 3 by

4. I punch the 3 and 3 appears on the LED display, called register X. Next I punch

the Enter key, and the 3 remains displayed but is also entered in unseen storage

register Y. Then I punch 4 and 4 appears in register X while 3 disappears from there

but remains in register Y. Finally I punch the multiplication key, and any numbers

in X and Y are multiplied together and the product appears in register X. Had I

punched the key you asked about before punching the multiplication key, contents

of the X and Y registers would have swapped places, and we would have seen the 3

again instead of the 4. Being able to do this is a help with some problems."

"How about the other two registers?"

"These are called the Z and T registers. When you punch the Enter key, anything

in register X is entered in register Y, anything in register Y moves to register

Z, and anything in register Z moves to register T. The key marked R↓ permits

'rolling down' the registers like a rotary desk calendar for viewing what they contain.

The CLR key clears any entry in X, while the CLR key clears all registers including

memory."

"What do you mean by 'memory'?" "That is a separate register in which you can

store a constant used repeatedly in a problem you're working with and recall it

whenever needed with a single key stroke. A displayed number is entered in the memory

by pushing the STO key and is recalled to register X by pushing the RCL key."

"I think I understand," Barney said slowly. "When working with an equation that

contains parentheses and brackets, it is often necessary to solve a portion of the

problem and then hold that answer until you solve another part to put with it. With

the HP-35 you don't have to resort to a scratch pad to do this. You simply poke

the partial answer up into the register stack and it drops back into the solution

when you need it. Okay; so that leaves only these CH Sand E EX keys to be explained."

"The CH S key changes the sign of a displayed number," Mac said. "The E EX key

means the next entries after it is punched are exponent digits. CH S must immediately

follow E EX for negative exponents. For example, to enter -0.0123 x 10-7,

you press CH S, .0123, E EX, CH S, and 7 in that order."

"How do they get all those smarts into that little bitty case?"

"With five especially designed MOS/LSI circuits using a new low-power, high-performance

ion-implant process. Each is equivalent to 6,000 transistors, making a total of

30,000 transistor functions in a case 5.8" long, 3.2" wide, and tapering from a

height of 1.3" at the display end to 0.7" at the other. And don't forget this case

that slips easily into your shirt pocket also contains a Ni-Cad rechargeable battery

pack that will operate the instrument for at least five hours before it needs recharging

from the 5-oz charger furnished with the HP-35."

"How much time can you really save by using it?"

"That's what Hewlett-Packard wanted to know; so they ran a capability study in

which engineers proficient in slide rule calculation and also familiar with the

operation of the HP-35 worked the same problems on the slide rule and the calculator.

In calculating the great circle distance between two points on the earth for which

the latitudes and longitudes were given, the time on the HP-35 was 65 seconds with

the answer to ten significant figures. On the slide rule it took five minutes to

get an answer to four significant figures. In working out the pH of a buffer solution,

the calculator again required 65 seconds to get an answer to ten significant digits

while the slide rule required five minutes to get an answer to three significant

digits.

"But time saved is not the whole story, although it certainly is important to

a college student loaded down with heavy assignments in all his subjects. Because

of tolerances in manipulation when several settings are involved, repeating a solution

on the slide rule rarely produces precisely the same answer. This is not true on

the calculator. If you feed in the same information, you get precisely the same

answer. And don't overlook the much greater accuracy with the calculator, plus the

great advantage of not having to keep track of the decimal point."

"You really are excited about this thing, aren't you?"

"That I am," Mac admitted. "For one thing, I'm glad to see an American company

coming out with a really outstanding calculator. I had begun to believe that only

the Japanese knew how to make minicalculators. But my enthusiasm goes deeper than

that. Man's relationship with numbers has always been a love/hate affair. On the

one hand he is fascinated with the mystery and power of numerical calculations,

but he dislikes the drudgery of making involved calculations involving large numbers

with pencil and paper.

"Down through the ages there have been breakthroughs in freeing him from this

drudgery in the way of easily carried calculating aids. First, probably, was the

Chinese abacus; then came tables of logarithms; next was the slide rule; and now

we have this shirt-pocket computer that can perform all these calculations we've

mentioned with lightning speed. Personally, I honestly feel the advent of the HP-35

marks an exciting event in the history of practical engineering."

"Okay, you're not going to get an argument out of me about that," Barney said.

"I yield to no man in hating to do long-winded calculations with a pencil. But now

the Big Question: How much does it cost?"

"Three hundred .and ninety-five dollars, including recharger, soft leather carrying

case, a safety travel case of molded plastic that holds both calculator and recharger,

and an operating manual. While that's not exactly peanuts, it's only a fraction

of what a non-portable desk-top scientific calculator capable of doing the same

things would cost."

"I only see one problem," Barney said, sliding from the bench and dusting off

the seat of his trousers.

"What's that?"

"How are you going to be able to surrender that little jewel to your nephew?"

"That's what's worrying me," Mac admitted as he reached out and patted the little

calculator fondly.

Mac's Radio Service Shop Episodes on RF Cafe

This series of instructive

technodrama™

stories was the brainchild of none other than John T. Frye, creator of the

Carl and Jerry series that ran in

Popular Electronics for many years. "Mac's Radio Service Shop" began life

in April 1948 in Radio News

magazine (which later became Radio & Television News, then

Electronics

World), and changed its name to simply "Mac's Service Shop" until the final

episode was published in a 1977

Popular Electronics magazine. "Mac" is electronics repair shop owner Mac

McGregor, and Barney Jameson his his eager, if not somewhat naive, technician assistant.

"Lessons" are taught in story format with dialogs between Mac and Barney. There

are 131 stories as of January 2026.

|

By John T. Frye, W9EGV, KHD4167

By John T. Frye, W9EGV, KHD4167

do?" Barney asked.

do?" Barney asked.