February 1960 Popular Electronics |

Table of Contents Table of Contents

Wax nostalgic about and learn from the history of early electronics. See articles

from

Popular Electronics,

published October 1954 - April 1985. All copyrights are hereby acknowledged.

|

Whoa! John T. Frye really

outdid himself in dreaming up a Rube Goldberg electronics contraption in this 1960

"Improvising" episode of his Carl and Jerry technodrama series in Popular Electronics

magazine. I have wondered whether he actually proves these concepts by building

what he describes the boys doing; it wouldn't surprise me if he did. Even if the

devices are purely theoretical, the description of the thought process and method

of practice is impressive. This being the beginning of the snow season in the northern

realm, the story's setting in a crippling snow storm is timely. It was potentially

a life-or-death situation, which triggered the classic "necessity

is the mother of invention" reaction. As fantastic as the action is, the fact

is there are thousands of people in the world who really are capable of performing

in that manner. I know a couple guys I am pretty sure fall into that category

(I'm not one of them -

heavy sigh).

Carl & Jerry: Improvising

By John T. Frye W9EGV By John T. Frye W9EGV

"Boy! It's slick as glass out there!" Jerry exclaimed as he peered through the

ice-coated windows of the bus in which he and his chum, Carl, were returning from

a shopping trip to Center City. "And look at what the ice is doing to those telephone

and power lines. I doubt if you could find a 500 -foot length of either all in one

piece."

"Yeah," Carl said in a low voice as he shut off the news broadcast he had been

listening to on his transistor radio; "and a howling blizzard that caught the weather

forecasters flat-footed is following up the ice storm. It's blanketing this whole

section of the country-"

"Folks!" the bus driver said suddenly, without

taking his eyes off the glazed road along which the bus was creeping. "We're going

to tie up at the next farmhouse. The road passes through a game preserve in the

middle of a swamp along here, and there won't be another house for five miles. With

driving conditions getting worse by the minute, we'd never make it. It's growing

dark, and we'd be foolish to take a chance on being stranded all night in a ditch

in this storm." "Folks!" the bus driver said suddenly, without

taking his eyes off the glazed road along which the bus was creeping. "We're going

to tie up at the next farmhouse. The road passes through a game preserve in the

middle of a swamp along here, and there won't be another house for five miles. With

driving conditions getting worse by the minute, we'd never make it. It's growing

dark, and we'd be foolish to take a chance on being stranded all night in a ditch

in this storm."

As he finished speaking, a dimly lighted window loomed out of the dusk on the

right side of the road; and there was a sniffing sound as the driver began lightly

touching the air brakes. The road through the swamp was built up on top of a high

grade, and the house was some eight or ten feet below the crown of the road. A black-topped

drive led from the highway across a culvert and into a garage beside the house.

The garage doors were open, and the car that evidently belonged in it was lying

on its side in the deep ditch at the end of the culvert.

The driver eased the huge bus to a stop on the highway opposite the house. At

that instant a bareheaded man came running from the house and scrambled and clawed

his way up the icy incline to the bus.

"Am I ever glad to see you!" he exclaimed to the driver as the latter opened

the door of the bus. "My boy's taken bad sick, and when I tried to get my car up

on the road to take him to the doctor, it slid off into the ditch. The telephone

and electricity have been out for hours. If a couple of you will help carry him

out-"

"We stopped here because we couldn't go any farther," the driver explained gently.

"We wanted to take shelter with you until the storm lets up."

The man's shoulders slumped as he turned towards the house. "Come on in," he

said lifelessly. "You're welcome, but I've got to get help for my boy."

As Carl and Jerry and the driver helped the

three women passengers down the slippery incline, the sleet suddenly changed to

snow; and the huge flakes came so thick and fast as to be almost smothering. But

inside the living room, dimly lit with an emergency coal-oil lamp, a cheery fire

in a large stove made everything warm and cozy. On a couch behind the stove a boy

about Carl and Jerry's age was writhing and moaning in pain. A white-faced woman

was sitting beside the couch and trying to keep cold cloths on the boy's head. As Carl and Jerry and the driver helped the

three women passengers down the slippery incline, the sleet suddenly changed to

snow; and the huge flakes came so thick and fast as to be almost smothering. But

inside the living room, dimly lit with an emergency coal-oil lamp, a cheery fire

in a large stove made everything warm and cozy. On a couch behind the stove a boy

about Carl and Jerry's age was writhing and moaning in pain. A white-faced woman

was sitting beside the couch and trying to keep cold cloths on the boy's head.

The youngest of the three women bus passengers walked over and touched the woman

on the shoulder. "Could I look at your son ?" she asked. "I'm a registered nurse."

The woman got up from her chair quickly, and the nurse sat down and began to talk

to the boy in that determinedly cheerful tone which is the trademark of the professional

healer. At the same time her fingers were gently probing his abdominal area. Suddenly

he jerked convulsively and cried out in pain.

"See if he can swallow these, but don't give him any water or anything else,"

the nurse said as she took a couple of tablets from a vial in her purse and handed

them to the woman; then she walked out into the kitchen where the men had gathered.

"I'm almost certain he has acute appendicitis," she replied to their questioning

looks. "The fever, nausea, and tenderness at the spot in his abdomen we call 'McBurney's

point' are classic symptoms. He says he began feeling bad this forenoon, and usually

an infected appendix should be removed no later than twenty-four hours after the

pain starts; but the sooner he gets to a hospital where they can run a blood count

and make other checks, the better it will he for him. Those pain tablets should

give him a little relief, and we'll use cold applications to slow things down. The

rest is up to you."

"I'll try to make it alone to the next house and get help," the bus driver said,

buttoning his jacket and starting for the door. Carl and Jerry followed the others

out on the front porch to see him take off. A howling wind was driving the blinding

snow almost parallel to the ground, and the flakes were so thick that the outline

of the bus, only seventy-five feet away, could barely be made out.

The driver turned on the lights, started the motor, and began easing power to

the Diesels. At first the bus refused to budge; then suddenly the rear wheels started

to spin and the rear of the bus slewed around into the driveway. Slowly, in spite

of everything the driver could do, the huge vehicle slid backward down the incline

until the rear of the bus came against a rock garden built in front of the house.

There it stopped, with the front wheels on the road and the headlights boring up

into the whirling snowflakes.

"I'm sorry," the driver said to the boy's father. "I didn't think it would work,

but I had to try. How about a couple of us trying it on foot?"

As if in answer, a voice from the transistor radio in Carl's hand said: "Attention

everyone in the storm area. Do not go outside. Stay indoors. This is the worst storm

in years. Winds are gusting up to sixty miles an hour, piling the snow into enormous

drifts. Even walking is impossible. Do not, I repeat, do not leave a place of safety

for any reason."

"Sir, do you have a radio in your car?" Jerry suddenly asked the boy's father.

"Yes, but why?"

"My friend here and I are radio hams. If you'll let us, I believe we can make

a transmitter out of your radio and summon help. We'd like to try."

"Go ahead. Doing anything is better than just sitting here. I suppose you want

the radio out of the car."

"Yes, and the battery, too. While you fellows

help Carl get them out, I'll try to move the tuning range of Carl's transistor receiver

into the 75 -meter ham band." "Yes, and the battery, too. While you fellows

help Carl get them out, I'll try to move the tuning range of Carl's transistor receiver

into the 75 -meter ham band."

"How you gonna do that?" Carl asked as he handed over his receiver.

"By taking turns off both the oscillator coil and the tuned loopstick antenna,"

Jerry answered. "If the transistor used as an oscillator will just keep going up

around four megacycles, this should work."

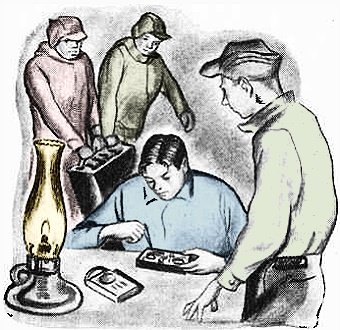

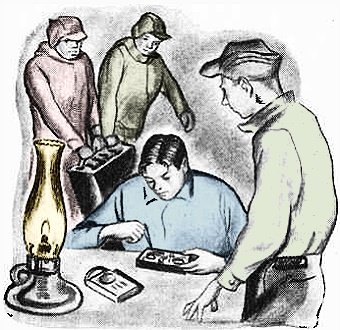

The man got some tools from his garage, and the three of them started to work

on the car. Jerry went back into the house and sat down at the table beside the

coal-oil lamp. With a pair of tweezers borrowed from one of the women, he fished

out the end of the oscillator coil winding he wanted and began carefully stripping

off turns. Every few turns he stopped and reconnected the end of the shortened winding,

then checked to see how far a broadcast station originally received at 1600 kilocycles

had moved down the dial. As this station grew weaker, he took turns off the loop

winding to peak it back up. Finally the station was coming in at 540 kc. on the

dial, and now when he tuned down to the other end of the dial he could hear some

weak amateur stations. By further trimming of the antenna coil and peaking up the

trimmer capacitors, he raised the volume of the ham signals until they could just

be understood.

At this point the men, plastered with snow and chilled to the bone, came in lugging

the car battery and the radio.

"Good old Hank is monitoring the state 'fone net' frequency as he always does when

there's a chance of a communications emergency," Jerry reported to Carl as the latter

held his blood-red hands towards the warmth of the stove. "If we can put out any

signal at all, he'll hear it."

Hank was a bed-fast amateur in the boys' home town who was noted 'both for his

technical knowledge and for his operating excellence. Any time that there was an

emergency on the ham bands, day or night, Hank could be depended on to be in there

with his keen ears and powerful signal.

"Hey, we're in luck!" Jerry exclaimed as he removed the top cover from the receiver.

"This thing uses push-pull tubes in the output stage. That means we can use one

of the power tubes as a self-excited oscillator and the other as a modulator. Am

I glad now I just finished reading an article on early tube transmitters! If I can

only remember the circuits-"

"You can and you will," Carl said with conviction. "You can't remember a three-item

grocery list for your mother, but I don't think you ever forgot a single line of

a circuit diagram in your whole life."

"Let's see, now," Jerry mused as he sketched a rough diagram on the back of an

envelope. "I think we'll tie the plate and screen of our oscillator tube together

and make a triode of it for the sake of simplicity. One section of this tuning capacitor

riveted to the chassis can tune the tank circuit, which means that one end of the

tank coil must be grounded. That's okay if we use this modified Hartley circuit.

The cathode goes to a tap near the grounded end of the tank coil. The other end

of the coil goes through a small capacitor to the grid, and a five- or ten-thousand-ohm

grid leak goes from grid to ground. The plate is at ground potential as far as r.f.

is concerned, and we'll tie it right to the plate of this other output tube serving

as a modulator. That will let us use 'Heising modulation.'"

"What are you going to use for a mike? You can't use the speaker without a transformer

to match its low impedance into a grid, and you're already using the output transformer."

"I'm going to use the carbon mike in the telephone handset."

"You still need a mike transformer."

"Not when I use the mike for the cathode resistor of my first audio stage so

as to make a grounded-grid amplifier of it," Jerry corrected.

A wood chisel heated in the stove served as a soldering iron as the two boys

made the circuit changes outlined. A thin copper tubing gas line found in the garage

was formed into a tank coil of some twenty well-spaced turns about two and a half

inches in diameter. This coil was simply allowed to lie on the wooden table top,

and leads from the tuning capacitor and the oscillator cathode were run to it. Tubes

not needed were removed from the receiver to save power. A dial lamp soldered across

a single turn of wire served as an oscillation indicator, and this lighted brilliantly

when held near the tank coil of the hay-wire transmitter; furthermore, it flashed

encouragingly when the mike was tapped.

Ice was broken off a 120-foot length of the downed telephone line in front of

the house, and one end, of this ,was connected directly to a turn of the tank coil

about one-third of the way down from the "hot" end. The other end was run out the

window and attached with a plastic napkin ring for an insulator to a telephone pole

that was still standing. The transmitter was tuned to the frequency on which Hank

and the other net members were talking by checking with the transistor receiver.

When all was ready, Jerry turned on the switch and gave Hank's call several times,

signed his own, and said. "Emergency traffic!" When the makeshift transmitter was

cut off, Hank's alert voice came from the little transistor receiver: "Station calling

with emergency traffic, go ahead. You're not very strong, and you have about as

much frequency modulation as you do amplitude modulation, but I think I can read

you. Other stations copy along."

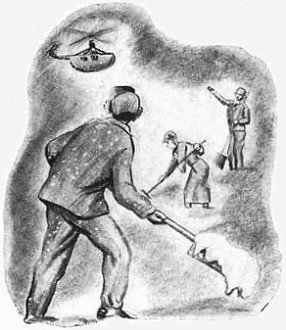

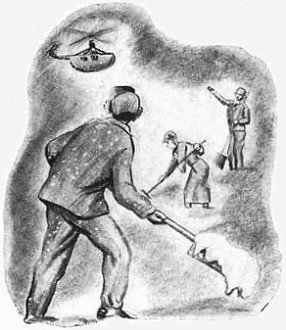

Quickly Jerry outlined their situation. Hank

gave him a "Roger" and told him to stand by. After a few minutes that seemed like

hours to the group whose tense faces were lighted by the coal-oil lamp, Hank was

back: "The state police are going to send out their 'copter to pick up the boy.

The storm is dying down, and they think they can make it if they can just find you.

Do you have any lights with which you can signal ?" Quickly Jerry outlined their situation. Hank

gave him a "Roger" and told him to stand by. After a few minutes that seemed like

hours to the group whose tense faces were lighted by the coal-oil lamp, Hank was

back: "The state police are going to send out their 'copter to pick up the boy.

The storm is dying down, and they think they can make it if they can just find you.

Do you have any lights with which you can signal ?"

"The headlamps of the bus!" the driver exclaimed. "They're pointed up in the

air!"

This information was relayed, and it was arranged that a portion of the highway

just south of the bus should be cleared for a landing spot for the helicopter. Everyone,

even the women, went out into the slackening snow storm to help scrape and shovel

the deep-piled snow from the road. They were barely finished when the throbbing

. sound of the whirlybird came from the sky, and in a matter of moments it settled

gently down on the road. The sick boy was carried out on the couch and transferred

to the aircraft, and it lifted up into the cone of light from the bus headlamps

and flew swiftly toward a waiting hospital.

Everyone went back into the house sat tensely around the little butchered-up

transistor receiver. Daylight was just breaking over the snow-smothered landscape

when Hank's sleepy drawl came from the speaker:

"All is well. The boy has just come down from surgery and is fine. The appendix

had mot burst, and there were no complications. A snowplow, followed by a wrecker,

is on the way out to you. Give me an okay, and then please take that alleged transmitter

off the air. I don't think I've had to copy a signal that lousy since I first got

my license thirty years ago!"

"Roger and out!" Jerry said with a grin as he patted. the improvised transmitter

affectionately; "I'd say, pretty is as pretty does!"

Carl & Jerry, by John T. Frye

Carl and Jerry Frye were fictional characters in a series of short stories that

were published in Popular Electronics magazine from the late 1950s to the

early 1970s. The stories were written by John T. Frye, who used the pseudonym "John

T. Carroll," and they followed the adventures of two teenage boys, Carl Anderson

and Jerry Bishop, who were interested in electronics and amateur radio.

In each story, Carl and Jerry would encounter a problem or challenge related

to electronics, and they would use their knowledge and ingenuity to solve it. The

stories were notable for their accurate descriptions of electronic circuits and

devices, and they were popular with both amateur radio enthusiasts and young people

interested in science and technology.

The Carl and Jerry stories were also notable for their emphasis on safety and

responsible behavior when working with electronics. Each story included a cautionary

note reminding readers to follow proper procedures and safety guidelines when handling

electronic equipment.

Although the Carl and Jerry stories were fictional, they were based on the experiences

of the author and his own sons, who were also interested in electronics and amateur

radio. The stories continue to be popular among amateur radio enthusiasts and electronics

hobbyists, and they are considered an important part of the history of electronics

and technology education. I have posted 86 of them as of February 2026.

p.s. You might also want to check out my "Calvin

& Phineas" story(ies), a modern day teenager adventure written in the

spirit of "Carl & Jerry."

|

-

Hello-o-o-o There - November 1962

-

The Hot Hot

- March 1964

-

The Girl

Detector - January 1964

-

First Case

- June 1961

-

The Bee's Knees

- July 1964

-

A Rough

Night - January 1961

-

Wrecked by a Wagon Train - February 1962

- Gold Is

Where You Find It - April 1956

-

Little "Bug" with Big Ears - January 1959

-

Lie Detector Tells All - November 1955

-

The Educated Nursing Bottle - April 1964

- Going Up - March 1955

-

Electrical Shock - September 1955

- A Low Blow - March 1961

- The Black Beast - May 1960

- Vox Electronik, September 1958

- Pi in the Sky and Big Twist, February 1964

-

The Bell Bull Session, December 1961

- Cow-Cow Boogie, August 1958

- TV Picture, June 1955

- Electronic Trap, March 1956

- Geniuses at Work, June 1956

- Eeeeelectricity!, November 1956

- Anchors Aweigh, July 1956

- Bosco Has His Day, August 1956

- The Hand of Selene, November 1960

- Feedback, May 1956

- Abetting or Not?, October 1956

-

Electronic Beach Buggy, September 1956

-

Extra Sensory Perception, December 1956

- Trapped in a Chimney, January 1956

- Command Performance, November 1958

- Treachery of Judas, July 1961

- The

Sucker, May 1963

-

Stereotaped New Year, January 1963

- The Snow Machine, December 1960

-

Extracurricular Education, July 1963

-

Slow Motion for Quick Action, April 1963

- Sonar Sleuthing, August 1963

- TV Antennas, August 1955

- Succoring a Soroban, March 1963

- "All's Fair --", September 1963

-

Operation Worm Warming, May 1961

-

Improvising - February 1960

|

-

Out of the

Depths - June 1957

-

ROTC Riot

- April 1962

-

Togetherness

- June 1964

-

Blackmailing a Blonde - October 1961

-

Strange

Voices - April 1957

-

"Holes" to

the Rescue - May 1957

-

Carl and

Jerry: A Rough Night - January 1961

-

The

"Meller Smeller" - January 1957

-

Secret of Round Island - March 1957

-

The Electronic Bloodhound - November 1964

-

Great Bank Robbery or "Heroes All" - October 1955

-

Operation Startled Starling - January 1955

- A Light Subject - November 1954

- Dog Teaches Boy - February 1959

- Too Lucky - August 1961

- Joking and Jeopardy - December 1963

-

Santa's Little Helpers - December 1955

- Two Tough Customers - June 1960

-

Transistor Pocket Radio, TV Receivers

and Yagi Antennas, May 1955

- Tunnel Stomping, March 1962

- The Blubber Banisher, July 1959

- The Sparkling Light, May 1962

-

Pure Research Rewarded, June 1962

- A Hot Idea,

March 1960

- The Hot Dog Case, December 1954

- A New Company is Launched, October 1954

- Under the Mistletoe, December 1958

- Electronic Eraser, August 1962

- "BBI",

May 1959

-

Ultrasonic Sound Waves, July 1955

- The River Sniffer, July 1962

- Ham Radio, April 1955

- El Torero Electronico, April 1960

- Wired Wireless, January 1962

- Electronic Shadow, September 1957

- Elementary Induction, June 1963

- He Went That-a-Way, March1959

- Electronic Detective, February 1958

- Aiding an Instinct, December 1962

- Two Detectors, February 1955

-

Tussle with a Tachometer, July 1960

- Therry and the Pirates, April 1961

- The Crazy Clock Caper, October 1960

|

Carl & Jerry: Their Complete Adventures

is now available. "From 1954 through 1964, Popular Electronics published 119 adventures

of Carl Anderson and Jerry Bishop, two teen boys with a passion for electronics

and a knack for getting into and out of trouble with haywire lash-ups built in Jerry's

basement. Better still, the boys explained how it all worked, and in doing so, launched

countless young people into careers in science and technology. Now, for the first

time ever, the full run of Carl and Jerry yarns by John T. Frye are available again,

in five authorized anthologies that include the full text and all illustrations." Carl & Jerry: Their Complete Adventures

is now available. "From 1954 through 1964, Popular Electronics published 119 adventures

of Carl Anderson and Jerry Bishop, two teen boys with a passion for electronics

and a knack for getting into and out of trouble with haywire lash-ups built in Jerry's

basement. Better still, the boys explained how it all worked, and in doing so, launched

countless young people into careers in science and technology. Now, for the first

time ever, the full run of Carl and Jerry yarns by John T. Frye are available again,

in five authorized anthologies that include the full text and all illustrations." |

|

By John T. Frye W9EGV

By John T. Frye W9EGV "Folks!" the bus driver said suddenly, without

taking his eyes off the glazed road along which the bus was creeping. "We're going

to tie up at the next farmhouse. The road passes through a game preserve in the

middle of a swamp along here, and there won't be another house for five miles. With

driving conditions getting worse by the minute, we'd never make it. It's growing

dark, and we'd be foolish to take a chance on being stranded all night in a ditch

in this storm."

"Folks!" the bus driver said suddenly, without

taking his eyes off the glazed road along which the bus was creeping. "We're going

to tie up at the next farmhouse. The road passes through a game preserve in the

middle of a swamp along here, and there won't be another house for five miles. With

driving conditions getting worse by the minute, we'd never make it. It's growing

dark, and we'd be foolish to take a chance on being stranded all night in a ditch

in this storm."  As Carl and Jerry and the driver helped the

three women passengers down the slippery incline, the sleet suddenly changed to

snow; and the huge flakes came so thick and fast as to be almost smothering. But

inside the living room, dimly lit with an emergency coal-oil lamp, a cheery fire

in a large stove made everything warm and cozy. On a couch behind the stove a boy

about Carl and Jerry's age was writhing and moaning in pain. A white-faced woman

was sitting beside the couch and trying to keep cold cloths on the boy's head.

As Carl and Jerry and the driver helped the

three women passengers down the slippery incline, the sleet suddenly changed to

snow; and the huge flakes came so thick and fast as to be almost smothering. But

inside the living room, dimly lit with an emergency coal-oil lamp, a cheery fire

in a large stove made everything warm and cozy. On a couch behind the stove a boy

about Carl and Jerry's age was writhing and moaning in pain. A white-faced woman

was sitting beside the couch and trying to keep cold cloths on the boy's head.

"Yes, and the battery, too. While you fellows

help Carl get them out, I'll try to move the tuning range of Carl's transistor receiver

into the 75 -meter ham band."

"Yes, and the battery, too. While you fellows

help Carl get them out, I'll try to move the tuning range of Carl's transistor receiver

into the 75 -meter ham band."  Quickly Jerry outlined their situation. Hank

gave him a "Roger" and told him to stand by. After a few minutes that seemed like

hours to the group whose tense faces were lighted by the coal-oil lamp, Hank was

back: "The state police are going to send out their 'copter to pick up the boy.

The storm is dying down, and they think they can make it if they can just find you.

Do you have any lights with which you can signal ?"

Quickly Jerry outlined their situation. Hank

gave him a "Roger" and told him to stand by. After a few minutes that seemed like

hours to the group whose tense faces were lighted by the coal-oil lamp, Hank was

back: "The state police are going to send out their 'copter to pick up the boy.

The storm is dying down, and they think they can make it if they can just find you.

Do you have any lights with which you can signal ?"