|

Television development was

a distant memory for most people during the dark days of

World War II. Germany's

forces launched its second siege of the 20th century against Europe in Fall of 1939.

By January of 1945, even the Brits were beginning to feel confident that the seemingly

endless days of World War II were about to come to an end. Hitler's forces

had been beaten back from its massive sprawl across Europe and into northern Africa.

Eisenhower's D-Day campaign six months

earlier had broken the back - and much of the will - of German forces. The

Battle of Leyte Gulf

shortly thereafter severely damaged Japanese naval forces. Slowly but surely improvements

were made in TV camera, broadcast, and local viewing technology in spite of the

severe restrictions placed on component and manpower availability, both in the UK

and in the U.S. John Logie

Baird was England's most famous television pioneer, having developed the first

practical broadcast system. His accomplishments were reported in this January 1945

edition of Radio News. Mr. Baird died the next year at age 57.

Television in Great Britain

By Leon Laden London. England

Mr. Baird's first demonstration of television in color and stereoscopic

relief.

Lattice television mast at the Alexandra Palace with for vision

(top) and sound (bottom) aerial arrays, with a signal carrier range of over 50 miles.

Colored stereoscopic television, as a result of John Logie Baird's latest invention,

the Telechrome, may become an outstanding feature of the postwar British television

industry.

A blueprint of postwar television, a sort of television Magna Charta, is now

being worked out by Britain's leading radio engineers, scientists, and manufacturers

serving on the Government Television Advisory Committee,1 appointed over

a year ago, to consider postwar development of television and advise the Postmaster-General

on future requirements.

This Committee already has taken evidence from representatives of the BBC scientists,

engineers, manufacturers, cinema and studio proprietors, and other bodies concerned

with the future of the industry. It can also be divulged, authoritatively, that

the Committee's findings and recommendations are expected to be made public within

a very short time.

Till then, however, the road along which the British television industry will

travel in the postwar period of its development or the signposts by which it will

be guided remain, necessarily, unconfirmed.

This contingency equally applies to the type of domestic receiver which will

make its appearance on the home and export markets and to the type of television

station that will transmit the outgoing programs.

The BBC's Post War Plans

No official yardstick, therefore, exists for the measurement of the BBC's future

television development and no statement on their peacetime policy has been authorized,

thus far, by either Mr. W. J. Haley, the new Director-General or Sir Noel Ashbridge,

Deputy Director-General in charge of Engineering.

Nevertheless, it is regarded as a certainty that the television service, closed

down on the 1st of September, 1939, will be on the air again soon after the termination

of hostilities, though in what form it is extremely difficult to predict, especially

since the BBC's Charter2 is due for renewal at the end of 1946, and much

water has flowed under the bridge since the Charter was granted over 21 years ago.

In spite of this, however, it is reliably reported that far-reaching plans for

the strengthening of the BBC's service are completed which call for the erection

of a super "Radio City" in the center of the British capital, incorporating the

entire broadcasting system and controlling every phase of its complex and ever-growing

work.

This new broadcasting nerve-center - for which building sites became available

when the tenement flats adjoining Broadcasting House were destroyed by enemy action

- will contain repertory theaters with a seating capacity for many thousands, big

concert and opera halls, and provision for television studios, control rooms, and

equipment.

Imaginative television programs providing a wide and varied pattern selection

of entertainment, information, and education to the people of this country, will

be produced in the "Radio City" and put on the air (as before the war) by the Alexandra

Palace transmitting station, linked with it by special coaxial cables.

A similar cable-route network will connect, in turn, Alexandra Palace with regional

relay transmitting stations in such centers of population as Manchester, Birmingham,

Newcastle, Glasgow, and Aberdeen, a chain of highly directive automatic relay stations

catering for the more sparsely populated areas.

It is estimated that this nationwide network, stretching from Land's End to John

o' Groats, and extending the range of television broadcasting to Britain's population

of some 45 million, will be completed within less than five years after the war's

end.

This outline is regarded to constitute the long-term policy of the BBC and also

comprise provision for color-television transmissions.

For the intervening span of time, the BBC plans to put into operation a less

costly and ambitious scheme consisting of high definition television, unchanged

in essentials from the pre- 1939 service; the higher standards will be introduced

by a "staggering" process as the super Radio City grows, the gargantuan network

strengthens its complex web of tentacles across the land, and the infant service

matures.

John Logie Baird shown with his color-television equipment, employing

the newly-designed Telechrome tube.

Black and White Versus Color

Amazing as the development of television may have been in the fifteen years of

its existence as a public service, it generally is agreed, nevertheless, that many

unchartered possibilities still will have to be explored before colored television

can seriously challenge black and white.

Mr. John Logie Baird has done more than anyone else to put color television on

the map and was the first to hit upon the brilliant idea of combining the antiquated

Victorian stereoscope with the familiar conception of the existence of three primary

colors (red, green, blue) in the visible light spectrum.

The information this 56-year-old television pioneer imparted to the author was

well worth the trip to the small country town where he has been living since his

London home was hit by a flying bomb.

"I am most optimistic about the possibilities of color television," Mr. Baird

said, and then he proceeded to paint a vivid picture of the revolutionary changes

television, and particularly color and stereo television, was about to effect in

our daily lives.

Perhaps the most interesting and significant features of it are associated with

the vast range of fresh opportunities which would be provided for the entertainment,

information, and education of the people while in their own homes.

But the highest place among the notable accomplishments of Britain's best-known

television authority belongs to his latest invention, the "Telechrome."

This excellent piece of new equipment was demonstrated last month to a small

gathering of members of the press. It has focused the attention of those interested

in television developments once more on colored stereoscopy, which possesses greater

possibilities than black and white and promises to become the outstanding feature

of the postwar British television industry.

In describing the Telechrome the inventor revealed that for the first time he

had perfected a cathode-ray tube capable of reproducing on the screen a coherent

picture of 600-lines in natural colors and stereoscopic depth without the aid of

intermediate filters.

"By utilizing a new form of scanning," Mr. Baird stated, "every line in the picture

is reproduced instantaneously and in the color it actually occurs. The revolving

discs and lenses which prevented the colored image from appearing directly upon

the fluorescent screen of the tube and made colored stereo television less efficient

and silent than black and white, have been eliminated."

The Telechrome already has been used with very good results, and stereo television

without the previously necessary colored glasses, now a visible practicability,

opens up an entirely new prospect for television.

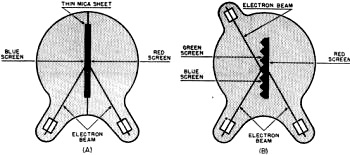

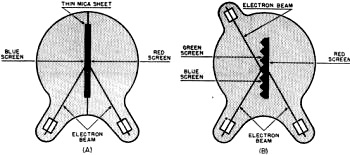

Fig. 1 - Telechrome tube construction: (A) for two-color

effect; and (B) for three color.

In Mr. Baird's opinion, however, there is not much likelihood that this broadcasting

medium would become available to the British public immediately after the war is

brought to an end in Europe or the Far East.

Another invention, on which he had been at work since the beginning of 1941,

was also mentioned by Mr. Baird.

"It is a special type of facsimile apparatus for automatic operation in connection

with the sending of telegrams, enabling enormous speeds to be obtained in the handling

and dispatching of cables," was the way its inventor described the apparatus, adding

that it was based on "a novel method of transmitting messages by television and

recording them photographically on a moving band."

The details of construction and operation of this new electronic device were

not revealed, however, owing to the wartime embargo on technical inventions which

may benefit the enemy.

Mr. Baird concluded this most interesting and informative conversation by presenting

the copy of a book entitled (eloquently) "Television-Today and Tomorrow" to which

he had contributed the foreword, and drew my attention to an account of one of his

earliest demonstrations of television in London, written in September, 1926, by

a special correspondent of Radio News (described in the book as "America's foremost

radio journal").

The account read as follows: "Mr. Baird has definitely and indisputably given

a demonstration of real television. It is the first time in history that this has

been done in any part of the world."

"This early testimony to practical television was the first to appear in print

in the United States, I think," were the last words of the man who has now added

another chapter to the history of television.

Postwar Plans of Manufacturers and Engineers

In talking to manufacturers of television equipment, one gathers that not color

and stereoscopy but economy (in materials) and simplicity (in design) will be the

keynotes of the postwar British television receiver.

"Premarketing tests show that an extensive market exists for an efficient and

fairly cheap television receiver," a member of the British Radio Manufacturers'

Association - the most powerful body in the radio industry - explained, adding that

he did not expect color television sets to be put into mass production before their

process of manufacture could be made as cheap and efficient as that of the black

and white ones.

Wartime view of camouflaged broadcasting house, London, showing

several antenna arrays and belt of concrete encircling ground floor as protection

against bomb blasts.

It is emphasized further by the manufacturers that they have spent large sums

on improving pre-1939 models and laying plans for the manufacture of these by mass

production methods at a reasonable price as soon as essential materials are released

and the official 'go ahead' is given. These moneys they maintain, would have to

be written off as a dead loss to the industry if overnight novel methods of transmission

were to be introduced, instead of gradually over a number of years. This applies

in their opinion, equally to the introduction of FM as well as to color and stereoscopy.

The British radio engineers share the manufacturers' view that this country's

peacetime television industry will be dominated more by economic than technical

factors, but suggest that in addition to black and white broadcasting for domestic

use, provision should be made for an alternative service of color television programs

for cinemas.

Regarding sound transmission, the engineers think it would be expedient to retain

prewar amplitude modulation for the London service in addition (or supplementary)

to frequency or pulse modulation, if and when either of these are introduced.

These views are expressed in a report submitted by the British Institution of

Radio Engineers to Lord Hankey, chairman of the Government's Television Advisory

Committee.

Among their other proposals of interest are recommendations for the formation

of a Radio Research Institute to study postwar possibilities in the ultra-high-frequency

spectrum, the adoption of cooperative research methods in the television industry,

and the standardization of domestic television receiver circuits. The report also

endorses the BBC's monopoly of television and the Government's control over available

wavebands.

It stresses, too, that "serious consideration should be given to better utilization

of the 4-mcs. bandwidth by making use of vestigial sideband transmission and also

to increasing the number of lines to that which is optimum for the increased modulation

bandwidth." Tentative figures proposed are 525-lines (gross, interlaced) and 3.25-mcs.

modulation frequency.

In general, the B.I.R.E. advocates "a television service broadly of a prewar

character, having characteristics in common with 1939 standards," and "a conservative

policy regarding the assignment of new frequencies."

In concluding, the Institution reminds the chairman of the Television Committee

that television is "the radio product that probably will be of the utmost importance

commercially, as judged by the immediate volume of business."

Postwar Applications Equipment

In spite of predictions that television may doom the motion picture theater,

the British film industry expects television's advent to boost cinema-going. At

least that is the opinion of Mr. Oliver Bell, the director of the British Film Institute

and Vice-Chairman of the British Councils' Films Committee.

"People get far more kick out of being in a large company at the movies than

looking at television in a small group round the fireside. Besides, you cannot pick

and choose as much with a television program transmitted from a broadcasting station

as you can at a movie theater which runs a continuous performance. Rather, it will

add attraction to the cinema in somewhat similar fashion as the Wurlitzer," this

cinema expert stated.

The British film industry is confident about the future. Elaborate plans have

been prepared for the alignment of the postwar cinema with television by at least

one leading British company of cinema-equipment makers and will be implemented as

soon as conditions are favorable. An official of the company concerned said that

they were prepared to risk their money to effect the cinema and television tie-up

and that they already had largely solved the multitude of technical problems connected

with the installation and operation of equipment in cinemas.

It appears, therefore, that the British cinema of tomorrow will be a "Telema,"

linked by coaxial cables with the transmitting station or central studio and equipped

with apparatus picking-up on prearranged wavelengths "live" television films and

"hot" news items. These will be actual occurrences televised on-the-spot and projected

onto huge viewers for the entertainment and information of the audience.

Another of the uses to which television equipment is to be put is crime detection,

the extensive employment of miniature television pick-up and projection apparatus

having been recommended by the British Home Office Committee on Postwar Development

of the Police to Mr. Herbert Morrison, the British Home Secretary.

This report calls for the training of selected constables in the operation and

maintenance of television equipment and the building of special projection theaters

where police officials can study televised films of scenes of crimes and life-size

replicas of known criminals.

Fifty-six year old John Logie Baird, holding his latest invention,

the Telechrome. This tube has a 10-inch diameter disc screen of thin mica, coated

blue-green on one side and orange-red on the other.

In view of these recommendations, as well as of the progress in television devices,

the time may not be far off, one London "Bobby" intimated when he hoped to be reclining

in a comfortable swing-chair in the viewing room of the police station and keeping

a televised "eye" on the welfare of the law-abiding citizen in the capital of the

British Empire.

Television, it is taken for granted over here, also holds much promise in store

for the expansion of Britain's postwar production capacity, although the industrial

branch of television engineering in this country, like in the United States, is

at present still in its infancy and the application of television devices to speed

up industrial processes is regarded as a laboratory day-dream.

Some idea of the shape of things to come, however, can be gauged by the fact

that variations of Zworykin's original Iconoscope are already being used for quality

control and routine inspection in several branches of the chemical industry.

It is anticipated, that these and most of the other "hush-hush" applications

which were the outcome of wartime research, will be revealed at the time of the

changeover from war to peace production.

Still another phase of television, which may be expected to benefit by the lifting

of wartime restrictions is the work of the British television amateur.

The British television "ham" had just about managed to elbow his way into the

short-wave fraternity and was still struggling for official recognition when the

outbreak of hostilities sounded the knell.

According to Mr. Geoffrey Parr, the secretary of the British Television Society,

this country's 400 television experimenters affiliated to his society are hopeful

about future developments.

Nevertheless, what the lot of the television "ham" will be after the return to

normal conditions in the wavelength spectrum or which, if any, bands of frequencies

will be allocated to him, remains a source of specula-tion as long as the Television

Advisory Committee's report continues to be held in abeyance.

In assessing current opinion about this country's television future in the transitional

and postwar periods, one gathers the impression, with some justification, that among

the developments which may be expected is the replacement of the present-day radio

set by the pre-1939 television receiver, fundamentally unchanged, in the British

home within a year or two after the last restrictions have gone; in what quality

or at what cost, however, there is no means of knowing at this stage.

Furthermore, it appears to be fairly certain, too, that after the elapse of another

few years, say somewhere around 1950, this black and white television receiver will

be ousted, in turn, by a receiver giving three-dimensional pictures in real color.

1 The equivalent of the U.S. Radio Technical Planning Board.

2 The BBC is a public corporation operating under Royal Charter and responsible

to the British Parliament.

Posted June 26, 2023

(updated from original post

on 10/23/2014)

Color and Monochrome (B&W) Television

Articles

|